One of the newest farmsteads added to the park inventory at Antietam is what we refer to as the Houser or Hauser farm. This small 7.6 acre parcel had been in private hands until 2006 when the National Park Service acquired it. Unfortunately there is very little semblance of the period buildings visible today and not that much has been written about the Houser farmstead, but we will do our best to tell the story of this eyewitness to history.

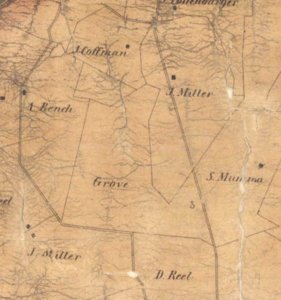

This farmstead was part of the land tract known as the Resurvey of the Addition of Piles Delight owned by John McPherson and John Brien, both well-known land speculators and owners of the nearby Antietam Iron Works. In 1814, they sold 225 acres of this tract to Philip Grove for $13,500. Michael Havenar also purchased a parcel just to the north of Grove, which would eventually become the Nicodemus Farm. This property lies west of what we know today as the West Woods and the Alfred Poffenberger farm. Within the deed there were indications that there were buildings located on this tract and a farm lane bordering the property to the south.

The Maryland branch of the Grove family descended from the German settlers of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Hans Groff emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1695 and his grandson Jacob moved to Maryland in 1765 where their last name was changed to Grove. Jacob’s son Philip would become one of the leading merchants in Sharpsburg, owning large estates in and around town. One of these estates was known as Mount Airy, a large farmstead just west of town which had been originally owned by the Chapline family. Philip purchased the property in 1821 and completed the building of the house, which became the Grove homestead.

Upon Philip’s death in 1841, Mount Airy was willed to his youngest son, Stephen P. Grove. The other tracts of land in Philip’s estate were divided among his other children. The 225-acre farm on Resurvey of the Addition to Piles Delight was divided between his daughter Mary Grove Locker and his son Joseph Grove. Since Mary resided in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, the eastern half of this property that she now owned was leased. Joseph on the other hand was most likely living on the 112-acre farm when he inherited it.

Joseph Grove was born in 1810 and married Susan Houser in 1836 when he was 25 years old. Susan was the daughter of Isaac and Barbara Mumma Houser. Over the next several years they had four children: Jacob, Lavinia, Jarrett, and Francis, or Frank. By the 1840s, most of the Grove property had been cleared of the old growth forest making way for cultivated land but small parcels of woods were retained and managed like the farmers crops. These woodlots provided lumber and cord wood as well as fence posts and shingles. There were still two small woodlots remaining on the Grove’s property and it bordered David R. Miller’s woods to the east.

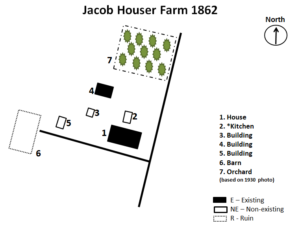

Like most of the farmsteads around the area, Joseph Grove’s farm had a large bank barn and a number of outbuildings surrounding the house. They also had an apple orchard just to the north side of the farm along the road leading to Mary Grove Locker’s farm. There is very little documentation of the farmstead or it’s layout except for a 1930 aerial photograph. Even though this photo was taken many years after this period, I believe it is fairly accurate of the mid 1800’s farmstead.

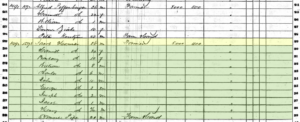

In addition to Joseph and Susan’s four children, there were two other people living with them in 1850. Fifteen year old, Eliza Bussard and Jacob Houser. Jacob was a younger brother of Susan. At 25 years old, Jacob was a farmer working with Joseph. Later that year Jacob would start his own family with his marriage to Harriet B. Grove, a niece to Joseph Grove.

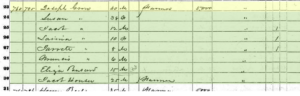

Unfortunately, there are many missing pieces in this story but we know tragedy struck the Grove family in late 1850. According to the Washington County death records, “Mrs. Joseph (Susan) Grove and child, died on Oct. 31, 1850”. They would be buried at the Reformed Cemetery in Sharpsburg. While we do not know the cause of death, it may have been due to childbirth or some disease like cholera. Sadly, Joseph died a few months later on December 7, 1850 and was also buried at the Reformed Cemetery. The following year the records show that a son of theirs died as well, and although a name is not listed it is believed to be Jarrett.

After the death of their parents it appears that the children went off to live with nearby relatives. Jacob Grove went to live with his uncle Stephen P. Grove at Mount Airy and became a silversmith. Lavina moved to Martinsburg to stay with Houser relatives, most likely her uncle Isaac Houser, and Frank Grove stayed in Sharpsburg to live with a relative Jeramiah P. Grove.

After the death of Joseph Grove in 1850, it appears that Jacob Houser took over stewardship of the farm until the children would come of age to take over or sell the property. Over the next several years, Jacob and Harriet Houser had eight children ranging in age from 10 years old to just under a year. Since the children were still young, Jacob needed a farm hand to help out around the farm, so 20-year old Samuel Piper was living with them. According to the 1860 census Jacob’s farm was valued at $5,000 and his personal property at $400. Sometime before September 1862, the three youngest Houser children: Joseph, Jacob, and Henry died and tragedy struck the Houser’s again on August 20, 1863 when the next youngest child George also passed away. Again the record is vague but it is reflected in the Sharpsburg death register and the census data.

The onset of the Civil War in 1861 tore many families and communities apart, especially in the border states and towns like Sharpsburg. Many men in the area would join the newly organized “Sharpsburg Rifles”, a Union militia company that would become part of the Maryland Potomac Home Brigade; while a number of young men traveled across the Potomac to Shepherdstown, Virginia to join up with Confederate units.

Frank Grove was just one of more than a dozen young men from Sharpsburg along with Henry Kyd Douglas, who lived just outside of town at Ferry Hill, that crossed over to join up in the Hamtramck Guards from Shepherdstown. Before leaving the Shenandoah Valley, they were tasked with the mission of destroying the covered bridge at Shepherdstown. Their unit became Company B, of the 2nd Virginia Infantry and would be part of the famed Stonewall Brigade under Thomas J. Jackson.

On September 16th, 1862 as the civilians in the Sharpsburg area were advised by the Confederate army to leave before the battle, roads quickly became crowded as families packed up some belongings and valuables to flee for safety. “The Houser family was among the refuges on the road that day. As the Housers shepherded their children along, a few stray bullets whistled past, and a shell hit a nearby fence, marking a lifelong impression on William Houser, then nine.”

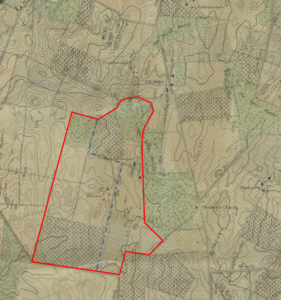

After ensuring his family was safe at nearby relatives away from the threat of the battle, Jacob returned to the farm to keep an eye on his property. At daybreak on the 17th, the Confederate artillery just north of the Houser farm, on the ridge at Nicodemus Heights, opened fire on the Union forces positioned around the Joseph Poffenberger farm. The battle had begun. Jacob spent the day hiding in his cellar as more Rebel troops moved up from Sharpsburg across his fields as they were fed into the fighting at the West Woods. Confederate artillery batteries repositioned around the farm to stop the ensuing Union forces from getting around the flank of Robert E. Lee’s fragile line. Sometime during the battle eight Confederates also sought shelter in the cellar with Jacob but then a “shell came through the wall and burst, killing four of the soldiers and wounding the others.”

Confederate Brigadier General Paul Semmes’ brigade of Virginians and Georgians advanced across the Houser farm and weighed in on the Federal troops at the Alfred Poffenberger farm. Semmes’ men, with help from the rest of Lafayette McLaws’ division, were able to push the Union troops though the woods to the edge of the D.R. Miller farm, but this gallant action cost his brigade dearly. Suffering over 50% casualties, including three of the four regimental commanders, the brigade was pulled back to a reserve position to replenish their ammunition on the Houser farm.

Antietam Battlefield Guide, Jim Buchanan points out on his blog, that many of the men from Semmes’ brigade would be buried right here on the Houser farm. Young William Houser remembered that the soldiers had been “buried very shallow, often were ploughed into, and of others in gutters being covered with brush and leaves, on the farm”. Many of these Confederate soldiers would be reintern into a Confederate cemetery at Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown in 1872.

After the battle, Jacob said nothing had been disturbed by the Confederates but even though “Jacob Houser was described as being pro-Union, neighbors told the Federal soldiers camped on the Houser farm that he was a Confederate. The troops destroyed much of the Housers’ personal property, ‘and what was left was hauled away by their neighbors and kept. Mrs. Houser was so terrified by that turn of events that she became ill, and kept to her bed for weeks.”

Before the Houser family could move back into their home extensive work had to be done to the house and the other buildings. “They had lost all of the food stored up for the coming winter as well as eight hundred bushels of threshed wheat. Soldiers had turned a drove of cattle loose in the Houser cornfield, and their hay had been lost, as well. ‘The only thing my wife and I had left’, Mr. Houser said, ‘was five hungry children.’ Jacob totaled his loses and submitted a bill for nearly $3,000. After years of fighting with the government, he received a little over $800.”

It is unknown how long after the battle the the Houser family moved off the farm, but they continued to live in the Sharpsburg District according to the subsequent census data. In 1881, Jacob Houser died and was initially buried in the Lutheran Cemetery but was later moved to Mountain View Cemetery to be interned next to his wife, Harriett who died in 1887.

In 1868 the farm was sold to George Burgan by Frank and Lavina Grove, the heirs of Joseph Grove. Less than ten years later, George Burgan would sell the farm to William Roulette in 1879. William was the grandson of Margaret and William Roulette. In 1880, the Shenandoah Valley Railroad was extending its service northward to Hagerstown. The line was to be built just to the west of Sharpsburg and William sold a small easement to allow for the railroad to go along his west property line. The farm stayed in the Roulette family until 1970, when the heirs of William Roulette sold the property to Leon Price. The following year, Price had sold a 7.6 acre parcel that encompassed the original house, farm buildings and orchard to Joseph Bell. In the late 1990’s, Price had sectioned four, 1-acrce parcels off to be sold off and developed for single family homes. These four lots along Mondell Road were part of the 112-acre farm.

In 2006, Joseph Bell entered an agreement with the National Park Service to sell his property with a clause to stay on for twelve years. After the Bell’s departed, the National Park Service became the full owners of the Houser farm. Like all the other farmsteads on the field, the Houser farmstead is just one more eyewitness to history and the Battle of Antietam.

Sources:

-

Ancestry.com, Joseph Grove Family, Jacob Houser Family, Census Data 1850-1880. Retrieved from: https://www.ancestry.com\

-

Buchanan, Jim, Walking the West Woods, 20 January 2021. Retrieved from https://walkingthewestwoods.blogspot.com/2012/02/searching-for-lavinia-grove-some.html

-

Ernst, Kathleen A., Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign, Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999.

-

Maryland. Board of Trustees of the Antietam National Cemetery, and 1869-1873 (Oden Bowie) Maryland. Governor. A Descriptive List of the Burial Places of the Remains of Confederate Soldiers: Who Fell In the Battles of Antietam, South Mountain, Monocacy, And Other Points In Washington And Frederick Counties, In the State of Maryland. Hagerstown, Md.: “Free press” print, 1868.

-

Maryland State Archives. Maryland Land Records On-Line, Washington County, January 5, 2021. https://mdlandrec.net/main/dsp_search.cfm?cid=WA

-

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Map of the battlefield of Antietam” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1864. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/185f8270-0834-0136-3daa-6d29ad33124f

-

Maryland Historical Trust, Frame Farmstead, WA-II-398, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, 1976.

-

Piper, Samuel W. Washington County, Maryland, Cemetery Records. before 1935-36. Western Maryland Historical Library. https://digital.whilbr.org/digital/collection/p16715coll31/search

-

O’Connor, Bob. Introducing the soldiers of Shepherdstown, Apr 15, 2011. Shepherdstown Chronicle https://www.shepherdstownchronicle.com

-

Reilly, Oliver T. The Battlefield of Antietam. [Hagerstown, Maryland: Hagerstown Bookbinding & Printing Co., 1906.

-

Taggert, Thomas, Map of Washington County. L. McKee and C.G. Roberton, Hagerstown, Maryland 1859.

-

Walker, Kevin M., Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape. Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

War Department. Army Air Forces. photographer. Antietam Battle Field, Md. The Hagerstown Pike. United States, 1930. December. Photograph https://catalog.archives.gov/id/23940809

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

Very well done Chris!

Thanks Tom.

Wonderfully researched and written, and what a great pen name> Also, a good reminder that families and farms outside the portions of the battlefield known for heavy fighting suffered as well.

Thank you Frank. This was the last of the farmsteads on the battlefield proper to write about, so from here on we will be looking at all those around the battlefield and Sharpsburg.

The Samuel Mumma Farm was owned by my 8th great grandfather. John Reynolds Sr.

Thank you, Chris, for researching and writing this. Jacob Houser was my 2nd great grandfather); one of his sons, Charles Buchanan Houser Sr, was my maternal grandmother’s father. This is by far the most comprehensive history I’ve seen of this side of my family, and I appreciate the work you put into compiling it.