On the morning of September 17, 1862, Major General Joseph Hooker rode out from the Joseph Poffenberger barn where he had spent the drizzly night. When he reached the edge of the North Woods and looked to the south he could see the objective of his Union First Corps – a small rise of ground at the junction of Smoketown Road and the Hagerstown Turnpike. Nearly a mile away, this intersection was next to a small whitewashed building, thought to be a schoolhouse but was actually the Dunker Church. Confederate forces under Stonewall Jackson defended the intersection in a line extending from the Mumma farm northwestward across the Hagerstown Pike through the woods to Nicodemus Heights. Halfway between Hooker’s First Corps and his objective at the Dunker Church stood the farmstead of David R. Miller. During the morning of September 17, the majority of the fighting would take place surrounding D.R. Miller’s farm – at the Cornfield, in the East Woods, along the Hagerstown Turnpike, in the West Woods and around the Dunker Church.

D.R. Miller Farmstead today.

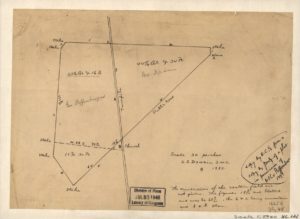

Like the Joseph Poffenberger farm, the D.R. Miller property was once part of the tract granted to Joseph Chapline called ‘Loss and Gain’ that was bequeathed to his son, James Chapline. In order to satisfy his creditors, James began leasing and selling parts of his land in the late 1790’s. Although there is no recorded lease or deed, it is believed that a John Myers was occupying on a portion of Chapline’s tract, now call “Addition to Loss and Gain“. In 1796, James Chapline sold 40 acres to Jonas Hogmire and that deed refers to “the part of Addition to Loss and Gain that John Myers now lives on..” Hogmire would also purchased another 40-acre lot from Chapline in 1797.

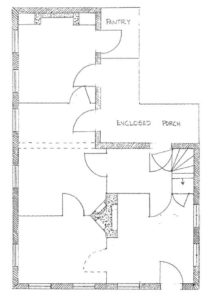

In 1799, Hogmire sold 81 3/8 acres to John Myers for £610, 6 shillings and 3 pence. Around this time the main house was built. The log structure sat on a limestone foundation with a central chimney system. “The chimney served the fireplaces of several rooms on each floor and was indicative of traditional Pennsylvania German floor plans”. The additional ell on the north side of the building would include a dining room, kitchen and porch. By the end of 1812, John Myers would acquire another 150 acres and several other smaller lots from James Buchanan, who was the Trustee for the sale of James Chapline’s land.

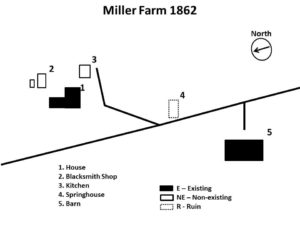

John Myers lived on the property until his death in 1836. According to his will, he directed that the farm be rented out for five years and that his daughter Kitty, “is to have and enjoy the free entire use and benefit of the mansion house in which I reside”. Based on the information in the will, the property included the “mansion house” and the “old house”. It is likely that the “mansion house” was referring to the house that is standing on the property today and the “old house” may have been a dwelling first occupied by John Myers, but being utilized as a tenant house in the 1830’s. Other improvements on the property included a second tenant house, a blacksmith shop, an out-kitchen, a spring and two gardens. The farm was divided by the “big road” referring to the Hagerstown-Sharpsburg turnpike. Across the turnpike stood the barn, a stable, a corn crib-wagon shed and hog pens.

In January, 1842 the property was put up for sale by the executors of John Myers will. An advertisement in the Hagerstown Mail stated that the farm consisted of “265 Acres of first-rate Limestone Land; about 150 Acres of which are cleared, the balance in thriving timber.“ In addition to the buildings there was an orchard of “fine Fruit Trees”. On April 24, 1844, David R. Miller purchased the farm for $53.00 per acre. That same day, David transferred the property to his father, John Miller, who was one of the executors. Although John Miller continued to own the farm until his death in 1882, his son David, known as D.R., would live there.

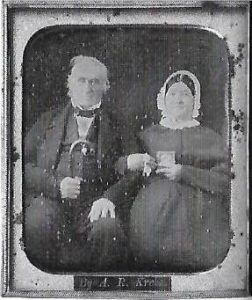

D.R. Miller was given his name in honor of his grandfather David Miller. David Miller and his wife, Catherine Flick, were from the Rhinepfalze region of Germany. In the 1760’s they emigrated to Maryland and established the first store in the new town of Sharpsburg in 1768.

David’s son John, followed in his footsteps operating not only the store, but the town post office, a hotel, a gristmill and also owned several farms. During the War of 1812, John was a colonel in the militia and continued to be referred to as Colonel Miller.

The very wealthy Col. Miller helped establish his sons on farms throughout the Sharpsburg area. On April 2, 1846, his son D.R. married Margaret Pottenger. Together they set up housekeeping and started to raise a family on the recently purchased farm. By September 1862, they had seven children and like the neighboring farms, they worked hard to harvest their crops that fall. Near the west side barn a number of haystacks stood and the garden was “sprawling with pumpkins, potatoes, and beans.” Just to the south of the farm was Miller’s 24-acre cornfield with “stalks higher than a man’s head” standing ready to harvest.

As the converging Union and Confederate armies neared Sharpsburg, Miller had his livestock driven to safety before they arrived, “all except one angry bull that refused to be herded”. The day before the battle, D.R. and his family left the farm and moved closer to safety at his father’s house on the other side of Houser’s Ridge. They made sure to take along the family’s pet parrot – Polly. As the fighting raged closer and the family moved into shelter, they realized that Polly was still in her cage on the porch. Just as D.R. ran out to rescue the petrified parrot on the porch, a shell fragment sliced through the leather strip and the cage fell to the ground as the squawking parrot cried, “Oh, poor Polly.”

While the Miller’s were sheltered at his father’s house, the battle raged back and forth across their farm, the fields and in the woods. Some of the most vicious fighting occurred in and around D.R. Miller’s cornfield. Gen. Hooker would write in his official report that, “every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they stood in their ranks a few moments before. It was never my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battle-field”. When Miller and his family returned to their home, the field was exactly how Hooker had described it, “not a single stalk left standing”. D.R. Miller’s field would forever be known as The Cornfield.

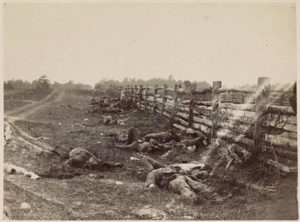

Confederate soldiers along Hagerstown Pike. D.R. Miller’s cornfield is just over the top of the fence rail in the distance.

During the battle Union casualties gathered at the farmstead, but were quickly moved to an established hospital further to the north. The days following the battle, Union burial details swept across Miller’s property, first to bury their comrades, than to bury the Confederates.

Union burial detail on the D.R. Miller farm. The barn roof can be see on the far right of the photo.

Surprisingly there was very little damage to the house and barn, only the blacksmith shop was destroyed. The crops in the fields were ruined and the stacks in and around the barn were used for the wounded and feeding the horses. David R. Miller filed a claim of $1,237.75 for damages of which he received $995.00 from the Federal government for his losses on July 6, 1872.

D.R. Miller and his family continued to live and work on the farm for the next twenty years. When Colonel John Miller died in 1882, he left a large amount of real estate, with eight children and no recorded will. This would place D. R. and Margaret against several of the other surviving heirs. After a bitter court battle it was agreed to sell the property and divide the money among the heirs. In November of 1882, 150 acres around the house and the farm buildings were put up for public sale. It is unclear what happened to the remaining 100 plus acres at the southern end of the property, but it is possible that they were parceled off and sold as well.

Eventually a year later, in November 1883, D.R. and Margaret purchased the farm they had been living on for almost forty years. A little over two years later they would sell the farm to Euromus Hoffman on March 29, 1886. Unfortunately the Miller’s did not enjoy a long retirement from the farm, for on November 13, 1888, Margaret passed away at the age of 63. D.R. survived until the age of 78, when he died on September 10 1893, almost thirty-one years after the battle. Margaret and David R. Miller rest together at the Mountain View Cemetery in Sharpsburg, near their neighbors, Joseph and Mary Ann Poffenberger.

The farm stayed within the descendants of the Hoffman family until 1933 when it was sold to John C. and Emma F. Poffenberger. In 1950, a widowed Emma Poffenberger would sell the farm to William and Lucy Barr who would only own it for two years before they sold the property to Paul and Evelyn Culler in 1952. On July 3, 1989, Paul Culler sold the farm to the Conservation Fund which would donate the property to the National Park Service in 1990.

Today, the D.R. Miller house has been stabilized and restored to its post-war appearance. A large portion of the farm is utilized by the National Park Service for their Living Farm program. The post-war outbuildings and fields are leased to local farmers to raise crops and livestock, generating some revenue but more importantly preserving the agricultural landscape of the battlefield.

The D.R. Miller farm was at the epicenter of the battle. According the a National Park Service ranger, the carnage here was some of the worst of the entire war. “There was a soldier killed or wounded every second for four hours straight”. This hallowed ground became the “bloodiest square mile in the history of the United States.” The D.R. Miller farmstead is a true eyewitness to history.

Sources:

-

Barron, Lee and Barbara Barron, The History of Sharpsburg, Maryland: Founded by Joseph Chapline, 1763. Sharpsburg: self-published, 1972.

-

Dresser, Michael, (September 13, 2012). 150 years later, Preservationists see victory at Antietam. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/bs-md-antietam-anniversary-20120913-story.html.

-

Ernst, Kathleen A., Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign, Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999.

-

Downin, S. S., Survey of the property of George Poffenberger and Mrs. Nicodemus in Washington County, Md, 1883. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/item/2005625029/.

-

Gardner, Alexander, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Selected Civil War Photographs Collection, Washington, D.C., 1862. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/related/?fi=name&q=Gardner%2C%20Alexander%2C%201821-1882

-

Reardon, Carol and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Antietam: experiencing the battlefield through history, places and people, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

-

Reed, Paula S., History Report: The D.R. Miller Farm, Hagerstown, MD: Preservation Associates, 1991: Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anti/miller.pdf.

-

Walker, Kevin M and K. C. Kirkman, Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape, Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols, Washington, D.C.; Government Printing Office, 1880-1901.

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

Leave A Comment