For over 260 years the property on which the William Roulette Farmstead would be established, has been under cultivation. The surrounding pristine countryside provides visitors to the Antietam National Battlefield a feeling of what the landscape looked like in September 1862 with the stone walls, wood lots, and old farm roads.

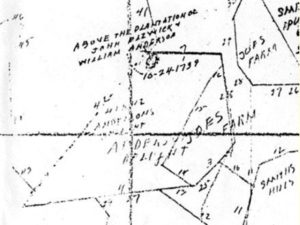

During the 1730’s Thomas Cresap had been a land agent for Lord Baltimore of Maryland. As Cresap began moving beyond the frontier, up the Potomac River valley, he began acquiring land. Cresap patented about 2,000 acres of land in Maryland along Antietam Creek, where he established a store and Indian trading post. In 1748 Cresap received a 212 acre patent named “Anderson’s Delight” from Lord Baltimore’s Land Office. As Thomas Cresap continued to move west he sold “Anderson’s Delight” to William Anderson, a Virginia farmer, in 1751. It is very likely that Anderson established the first dwelling on the land that would become the Roulette Farmstead. Anderson would only own the property for ten years before selling it to John Reynolds.

In 1761, John Reynolds, an Anglo-Irishman who migrated to Washington County from Lancaster County Pennsylvania, acquired the 212 acres of Anderson’s Delight for 235 pounds. In 1764, Reynolds would add another 138 acres to his holdings from Joseph Smith from three other land grants. In 1765, Reynolds had acquired another 35 acres from Joseph Chapline. According to the Washington County Assessment of 1783, Reynolds’ farm had “76 acres of arable land, 4 acres of meadow, and 112 ½ acres of woodland. In addition, he had 5 horses and 32 “black cattle” or beef cattle. Some of the crops grown most likely included corn, wheat and rye.

During this time it is likely that Reynolds built one section of the extant farmhouse, but the family had been living in the dwelling that Anderson built, possibly the springhouse / kitchen. John Reynolds continued to farm this property until his death in 1784. According to Reynolds’ will, the 385 acres was divided between his two sons, Francis and Joseph. Joseph had acquired the family farmstead while Francis’ acreage just north west of the farm would later become the Samuel Mumma farm.

Joseph Reynolds quickly added two additional parcels; in 1785, he acquired 45 acres from Joseph Chapline and in 1789, he acquired 51 acres from James Vardee. Both were part of a patent called “Joe’s Lott“. Also in 1789, Joseph Reynolds added another 240 1/4 acres to his holdings through a land grant he obtained directly from the Land Office which was named, “Joe’s Farm“. Over the twenty years that Joseph owned the property, he would continue to expand his agricultural operations and continue on the construction of the the main house and the spring house. It is believed that Reynolds owned slaves, but that he had set them free in 1794.

In 1804, Joseph Reynolds sold off several parcels of his property, so the farm totaled 262 acres when John Miller purchased it. Miller was a Pennsylvanian German from Franklin County. He had migrated to Washington County with his parents around 1791. His father, John Johannas Hannas Miller, was a member of the Church of the Brethren, also known as Dunkers. Like Reynolds, John Miller was a farmer and he continued to cultivate the land.

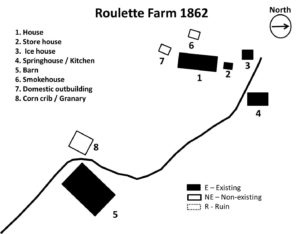

During this time, Miller would most likely complete the building of the farmstead. He added the northern section of the house,a log kitchen addition which include a unique beehive oven. Miller added onto the springhouse, constructed the icehouse and a smokehouse as well. The Miller family would also update the interior of the house, adding molding and trim of the period.

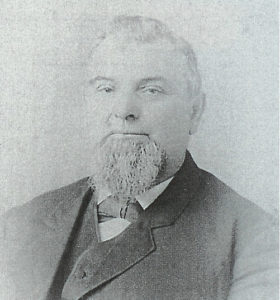

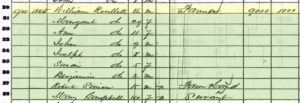

By 1840, the farmstead had passed to John Miller IV who continued the family farming until his death. In 1851, his widow Ann Miller would sell 179 1/4 acres of the farm to the husband of Margaret Ann Miller, a sister of John IV. Her husband’s name was William Roulette. The Roulette family had been in Washington County since before 1774 and William was raised on a nearby farm. Margaret had lived on this property her entire life. They were married in 1847 and their first child was born in 1849. When they moved into the farm and set up housekeeping their second child arrived. By 1862 they had six children ranging from age 14, to their youngest, Carrie May who was just 19 months old.

It is almost certain that William Roulette constructed the large bank barn to sustain his growing agricultural operations. The Roulettes had a variety of livestock on the farm such as horses, milk cows, cattle, sheep, swine and poultry. William had a slightly larger herd of beef cattle than most farmers in the Sharpsburg District. They also grew a variety of grains including corn, wheat, oats and rotated rye. The Roulette’s had established a four-acre orchard near the house and their vegetable garden stretched between house and barn.

To help with the farming operations, William Roulette most likely had hired hands. Although it is not sure when it was constructed, there was another 1 1/2 story structure on the property located along the Roulette Lane near the southwest corner of the orchard. This may have been used by a tenant farmer or hired hand by the name of A. Clipp.

View of the Roulette Farm from the Observation Tower. Clipp house near the barn just below the farm house. cir. 1900

The Roulette’s did not own any slaves but employed two free blacks. According to the 1860 Census, 15 year old Robert Simon was a farm hand and 40 year old Nancy Camel (Campbell) worked as a servant. Nancy was born a slave on a farm in Washington County owned by Andrew Miller, Margaret Roulette’s uncle. Miller had freed Nancy in 1859.

On Sunday, September 14, 1862 the Roulettes, like their neighbors the Mummas, were becoming increasingly concerned over the sounds of battle coming from South Mountain. By Tuesday morning, as soldiers from both armies began to converge on their farming community, William took his family to safety at the Manor Church of the Brethren, six miles to the north. With his family safe with the Dunker congregation, William Roulette returned to his farm to check on his property, gather some supplies and tend to his livestock. Once at the farm, William found himself caught between the Confederate and Union lines as the battle erupted on his property.

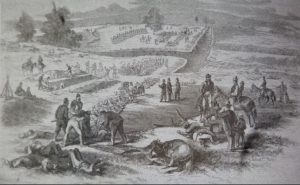

By mid-morning the battle lines had shifted past the Dunker Church plateau. Union forces were now moving across William Roulette’s property toward the rutted farm lane known as the Hog Trough Road or Sunken Road, to strike the center of the Confederate line. Confederate skirmishers were using some of the outbuildings as cover when the Union forces pushed them back to their position at the Sunken Road. William Roulette, a pro-Union man, had been hiding out in his cellar away from the Confederates. Now that the Federal forces had begun to push them back, William came out in the midst of the fighting “to see what was happening, and he cheered the men in blue on: ‘Give it to ’em! Drive ’em! Take anything on my place, only drive ’em!’ he yelled”

As more Union troops moved through the Roulette backyard, a Confederate artillery shell landed, shattering the rookies of the 132nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. In their flight to get out of the area they knocked over Mr. Roulette’s apiary. “Yelping Pennsylvanians scattered as thousands of angry honeybees swarmed over them”. Over the next three to four hours, Union attacks struck the Confederates in the Sunken Road, finally breaking their line and pushing them back to the Henry Piper farm. Over 5,000 casualties of both sides laid in and around the road now forever known as “Bloody Lane”. Union casualties were taken back to the Roulette barn and the farm road intersection by the barn was used to pick up casualties to transport them to other Union hospitals nearby.

Like their neighbors, the Roulettes were left with damage to their buildings and devastating losses to the crops, fields and fencing. The traumatic sight of dead bodies strew across their property and in the road was unbearable. After the battle Union soldiers began burying their dead across the fields, near the roads and hedgerows and marking the graves. Two days later, Union burial crews drug the bodies out of the lane and buried the Confederate soldiers in long shallow graves on both side of the Roulette Farm Lane. Mr. Roulette would say that over 700 bodies were buried on his property.

Several weeks later William Roulette would file a claim for damages and loss of property requesting $2496.27 for an “inventory of goods, chattels, and personal effects belonging to me which were destroyed and carried off by the Armies during the late battle of Antietam”. According to the quartermaster of the Army of the Potomac, the claim was rejected stating, “I am well aware that the loyal people of this section of Maryland have suffered severely during the campaign… I regret that they cannot receive full compensation now for their losses, but no disbursing officer with this Army is authorized to pay claims for damages. Such claims can only be settled by express authority of congress.” William would continue to submit claims into the 1880’s but would only receive $377.37 from a hospital claim.

On October 21, 1862, tragedy struck the Roulette family when they lost their youngest daughter Carrie May to typhoid fever. She was one of a number of Sharpsburg residents that would die as a result of the battle. Despite the great loss he suffered, William Roulette remained a strong Union man. After the war was over, Margaret and William would have another son, Ulysses Sheridan Roulette – born on October 15, 1865. As time went on the Roulettes would rebuild their farmstead. Although the older children had moved off the farm, the two youngest sons – Benjamin and Ulysses helped with the farm work and Susan, the youngest daughter who was still living at home, helped with chores. Nancy Camel would continue to work for the Roulette family until she died in 1892.

In 1883, Margaret Ann passed away. Four years later, William retired from farming and moved into the Town of Sharpsburg, turning over the farming operation to his son Benjamin. William died in 1901 at the age of 75. Margaret and William are buried together in the Mountain View Cemetery with their children, Carrie May and Otho.

In 1890, the Antietam National Battlefield Site was established by the War Department. They would construct a road to the south side of the Sunken Road, called Richardson Avenue, and build a sixty foot stone observation tower on the southeastern edge of the Roulette farm adjacent to Bloody Lane. Over the following years the war veterans would return to the Roulettes to hold reunions and reminisce about that day in September, 1862.

Although William died without a will, the family conveyed the property to Benjamin Roulette. Benjamin married Elizabeth Brown Rhoades in 1886 and together they had four children. Benjamin was said to be “a progressive farmer whose crops were consistently among the best in the local market.” He also specialized in raising market hogs. Benjamin owned the property from 1901 until his death in 1947. Like his father before him, Benjamin died intestate, but the property managed to stay in the family when it was conveyed to his youngest son, Samuel Patterson Roulette.

Samuel and his wife, Leoda, continued to live and farm the property until 1956. For the first time since 1804, the property passed out of the Miller-Roulette families when they sold it to Howard and Virginia Miller (a different Miller family). The Millers lived on the property for forty-two years and were good stewards of the land. In 1998, the Richard King Mellon Foundation purchased the farm for $660,000, and donated it to Antietam National Battlefield.

Today the Roulette Farm fields are leased to local farmers, who continue to utilize the property for it agricultural production. The William Roulette Farmstead remains an icon on the battlefield, displaying the architectural history of the developing farmsteads of the area. It reminds us of what the agricultural landscape looked like before it was an eyewitness to the bloody fighting along the Sunken Road.

-

Ancestry.com, 1860 United States Federal Census for William Rowllett. Retrieved from: https://www.ancestry.com\

-

Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), Nancy Campbell (Camel). Retrieved from http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5400/sc5496/024600/024669/images/campbell_nancy_01_001.pdf.

-

Burrows, Jim, Anderson Papers: Anderson’s Delight. Retrieved from http://www.eldacur.com/~burrowses/Genealogy/Anderson/AndersonsDelight.html

-

Ernst, Kathleen A., Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign, Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999.

-

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/related/?fi=subject&q=Antietam%2C%20Battle%20of%2C%20Md.%2C%201862.&co=cwp

-

Reardon, Carol and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Antietam: experiencing the battlefield through history, places and people, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

-

Reynolds, Marion, H. Ed. , The Reynolds Family Association, Annual Report. Brooklyn, NY, Press of Brklyn Eagle, 1922. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=4iFMAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA200&lpg=PA200&dq=John+Reynolds,+Sharpsburg&source=bl&ots=Tf_25HO2wU&sig=v9Y17b6ZDnb8ejGvAWP5E4FCfAg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwif4O794pXUAhUGQyYKHelzDE8Q6AEILTAC#v=onepage&q=John%20Reynolds%2C%20Sharpsburg&f=false

-

U.S. National Park Service, Roulette Farmstead Cultural Landscape Inventory, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2004.

-

Walker, Kevin M and K. C. Kirkman, Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

The tenant farmer that worked with Mr. Roulette was Hiram Clipp, my great great great Uncle. He was wounded while in service of the Confederate Army and moved to Maryland with his wife in hopes of a more peaceful life. During the battle, Uncle Hiram and his wife Catherine took shelter with the Roulette’s and, after the fighting, took care of the wounded. I thought I’d share. Happy New Years