The one farm house on the Antietam Battlefield that looks the same as it did on September 17, 1862 is the Sherrick House. When you stand in front of the house and hold up the historic photograph taken of the farmstead, it’s as if you traveled back in time. The photo captures the Sherrick Farmstead; the bank barn, out buildings, fences, garden and the unique brick house. Looking at it you can imagine what life was like on the farm.

The property we now know as the Sherrick Farm was once part of the Smith’s Hills patent that was granted to James Smith on January 26, 1756. As the French and Indian War was ending, Christian Orndorff, a millwright from Lancaster County, arrived in the area in 1762. Orndorff purchased 503 acres from James Smith along the Antietam Creek. Of course, Christian Orndorff would establish a successful milling operation at the location of the Middle Bridge on what is known today as the Newcomer Farm. Prior to his death in 1797, Christian Orndorff divided his holdings among his sons Christopher, Christian and Henry.

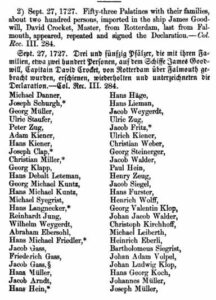

Over the years as the milling industry grew along the Antietam Creek. That prosperity drew more and more migration from Pennsylvania. In 1796, Joseph Sherrick, his wife Barbara Hertzler and their young daughter also named Barbara, left Lancaster County, Pennsylvania with his brother-in-law Jacob Mumma and his family. The traveled down the Wagon Road to Sharpsburg. Joseph’s grandfather was also named Joseph but the last name was spelled Shrek or Schurgh. Born in Switzerland, Joseph and his wife Catherine “left Rotterdam Harbor, Holland in early July on the ship James Goodwill, commanded by David Crockatt, and arrived at Philadelphia on September 27, 1727″. From Philadelphia, they moved to Hempfield Township, Lancaster County. It was here that the Sherrick family became friends with the Mumma’s, the Hertzler’s and many other families that would move southwest into the Antietam Valley.

Once they arrived to the Antietam Valley, Jacob Mumma would purchase over 300 acres from Christopher Orndorff which included the site of the mill, while Joseph Sherrick purchased the adjoining property to the south, 194 acres from Christopher’s brother, Henry Orndorff.

According to the 1796 deed that land may already have been established as a farm. In the deed there is reference to existing “houses, outhouses, barn, fields, woods, under woods, meadows, orchards, hereditaments and appurtenances“, and there is reference to a “water ditch that is made for the use of watering the meadow.” That ditch was the Town Run, a small stream that ran down from Sharpsburg, past another mill through the farm as it made it’s way to the Antietam Creek. The Sherrick’s most likely stayed with the Mumma’s until they could establish their home on the property the following year, but it’s presumed that a log or timber frame structure served as their house. Soon after setting up the home, Joseph and Barbara would have two more children, Jacob born in 1798 and Joseph, Jr. in 1801.

Tragedy stuck the Sherrick family a few years later when Barbara Hertzler Sherrick died at the aged of 37 in 1804 leaving Joseph, Sr. with three children. She was buried at a nearby cemetery that would become known as the Mumma Cemetery. Needing a wife and a mother to raise his children, Joseph, Sr. married Barbara Mumma, Jacob’s sister.

In 1833, the Washington County Commissioners contracted John Weaver to select a location to construct a bridge over the Antietam Creek on the Sharpsburg and Maple Swamp Road. This road traversed Sherrick’s land along the Town Run to the Antietam. Weaver selected a site near the edge of Sherrick’s southern property line, most likely due to the the fact that limestone could be quarried off the hillside. The bridge was completed by 1836 for a cost of $2,300. Soon after it’s completion the Sherrick’s constructed a stone wall on the east side of the creek.

Joseph, Sr., subsequently enlarged the farm by purchasing additional nearby parcels of land in 1821, 1826, and 1833. On April 15, 1828, young Joseph, Jr. married Sarah Hamm. It’s believed that young Joseph and Sarah ventured west to Ohio according to the 1830 census. Their stay in Ohio was not long-lived and by 1836 the young couple had returned home with a daughter, Mary Anna. Joseph, Jr purchased tracts of property around the family farm and in 1838 he acquired the land owned by his father.

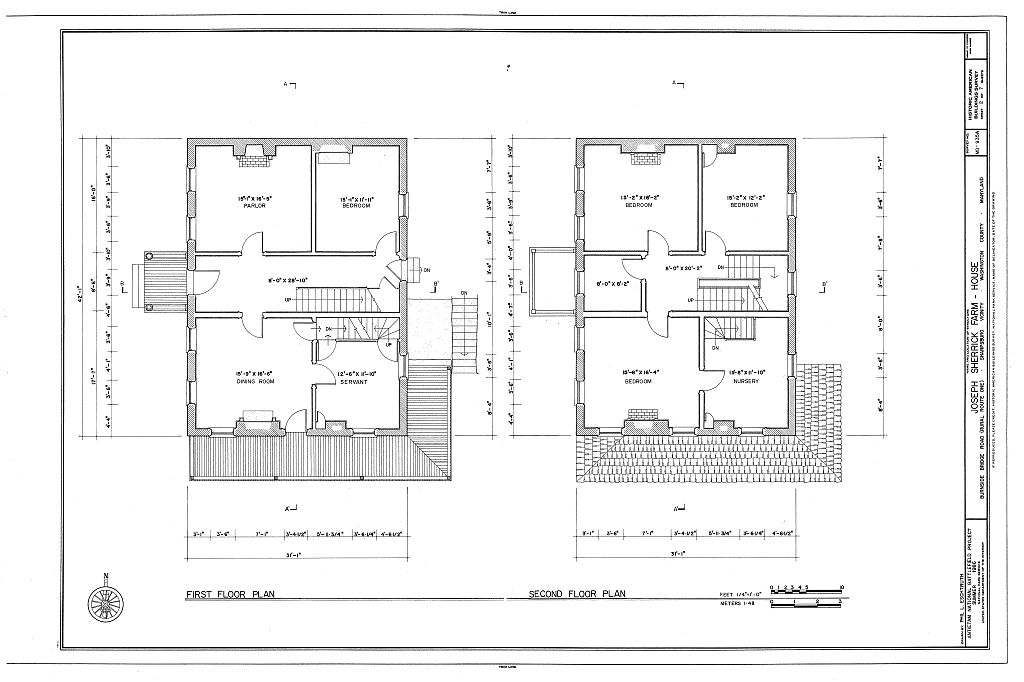

It is around this time that the home the Sherricks had been living in for over thirty years was replaced with the brick structure we see today. Like their neighbors across the Antietam, the Pry’s, this new house reflected the “most current trends in architectural design, incorporating vernacular elements of Greek revival style of the 1830’s”. The Sherrick’s house would be very unique, it was built into the slope much like their traditional Pennsylvania bank barn but it was also constructed over a fresh water spring. This fresh water flowed into a spring room in the sub-basement. Water could be drawn from the spring room to a kitchen just above in the basement. Also in the basement was a large fireplace and an adjoining room that was used as a small pantry.

The first floor consisted of a dining room, parlor, bedroom, a servery and large stair hall. The impressive hall included a “wide entry door, crowned by a divided transom”, “high ceilings, gracious moldings, and wood grained doors”. But the staircase was the most striking, as the broad staircase lead to a landing, “The risers of these stairs and the baseboard moldings throughout the hall were painted to look like marble, a technique common during the Greek revival period”. (This style was replicated in the foyer at the Jacob Rohrbach Inn.) Three bedrooms and a nursery were on the second floor and another unique aspect included service stairs from the nursery to the servant room and down to the kitchen. The Sherrick house “was one of the most well appointed farmhouses in the Sharpsburg area”.

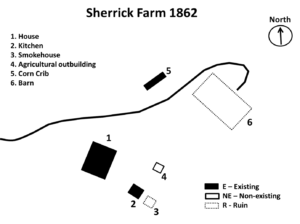

Behind the house was their 1 1/2 story brick summer kitchen with a large hearth fireplace, bake oven and a staircase to the upper story where meats were hung. A stone-built smokehouse was located just behind the summer kitchen and was probably built as a “dependency of the original Sherrick house’. The large 45′ x 90′ Pennsylvania-style bank barn sat on the hill beyond the house. This was the original barn that was constructed by either Henry Orndorff or Joseph Sherrick, Sr. between 1790 – 1800. On the northwest side of the barn was a fenced 2-acre orchard and adjoining garden. A number of other outbuildings and structures were on the property but today there is only evidence of a few.

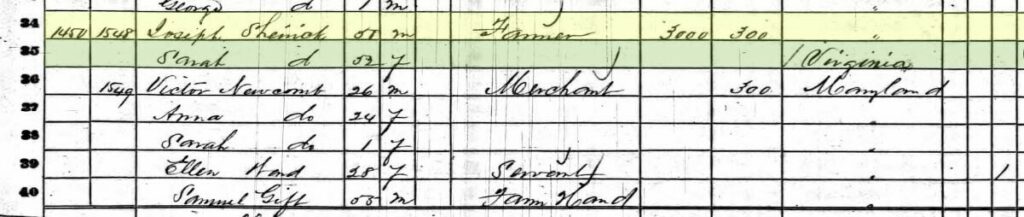

The Sherrick farm prospered over the next decade. According to the 1850 census the farm was valved at $12,000. The Sherrick’s were members of the German Baptist Brethren or “Dunker” congregation. The Dunkers had been meeting in the private home of Daniel Miller, the father of Elizabeth Miller Mumma. In 1851, Samuel Mumma donated a small plot of land at the edge of a woodlot that would become known as the West Woods. Daniel Miller, Samuel Mumma and Joseph Sherrick supervised the construction of the new church. It was constructed with hand-made clay bricks from John Otto, Joseph Sherrick’s neighbor.

In May, 1858, Mary Anna Sherrick married Victor Newcomer, a merchant. The following year they would have their first child and continue to live with her parents. According to the 1860 Census, the family was still residing on the farm. A young female servant named Ellen Ward and Samuel Gift, a farm hand lived at there as well.

Around this time Joseph Sherrick retired from farming and leased the farm to a young man named Leonard Emmert. “At that time, the farm consisted of 200 improved acres and 20 unimproved acres and was valued at $14,000. Livestock was valued at $500. During the year ending that June, the farm produced 1,500 bushels of wheat, 20 bushels of rye, 1,000 bushels of Indian corn, 150 bushels of oats, 100 pounds of wool, 50 bushels of potatoes, $20 in orchard products, 500 pounds of butter, 25 tons of hay, and 12 bushels of clover seed”. It is unsure where the Sherrick family moved to, possibility Boonsboro, but Leonard Emmert was still leasing the farm in the fall of 1862.

On the morning of September 15, 1862, Confederate forces under Robert E. Lee were falling back from their defeat at South Mountain. But when Lee reached the Antietam Creek he stopped. His small army went into a defensive mode around the town of Sharpsburg in order to wait for the rest of Lee’s men under General Stonewall Jackson to arrive from Harpers Ferry. Near the Sherrick farm, Confederates under General David R. Jones’ division were positioned. By the Rohrbach Bridge just down the road from the farmstead a Rebel brigade was posted on the heights above the bridge and along creek to prevent Union forces from easily crossing. They were supported by Confederate artillery on hilltop across the Otto farm and on Cemetery Hill. Confederate skirmishers were stationed across the fields waiting for the pending battle.

The battle on September 17 began at daybreak, but it seemed that it was happening to the north of Sharpsburg with the exception of the artillery batteries dueling back and forth. About mid-morning, the Union Ninth Corps under General Ambrose Burnside began their assault against the Confederates to take the bridge and cross the Antietam Creek. The Rebel forces were able to hold off the Federals for about three hours before they finally gave way and withdrew to the high ground along the Sherrick farm lane. To the north of the Sherrick house Union forces crossed over the Middle Bridge at the Newcomer or Mumma Mill and began pressing skirmishers and artillery forward.

By 3:00 pm, the Union Ninth Corps was across the Antietam and in position to began their assault against the Confederate right. The Union battle line stretched for almost a mile, from the Sherrick’s 40-acre cornfield in the south, to the Otto farm, across the Rohrbach Bridge Road and through the Sherrick farm. Burnside’s right flank tied into elements of the Union Fifth Corps as they advanced up the Boonsboro Pike through Sherrick’s fields north of the farmstead. The 79th New York Infantry advanced in a double line of skirmishers across the farm as they spearheaded the advance of Colonel Benjamin Christ’s brigade. When the 79th New York reached the Sherrick house and outbuildings they met stiff resistance from South Carolinian’s in an apple orchard and around the building of the Solomon Lumm mill. Heavy artillery fire from Rebel guns on Cemetery Hill stalled the advance as Christ deployed his three other regiments to move west across the Sherrick farm.

With support from Union artillery batteries, Christ advanced as Col. Thomas Welsh’s brigade pushed up the Sharpsburg Road to his left, dislodging the Confederates, forcing them to withdraw. As Welsh’s men continued to fight their way to the outskirts of town, the far right flank of the Ninth Corps line was being stuck by General A.P. Hill’s Confederate troops in the middle of the 40-acre cornfield. With the line slowing collapsing and men running low on ammunition, the Union troops were forced to fall back to their starting point.

Union causalities were being treated at the Sherrick and Otto farms as ambulances evacuated the wounded further to the rear to field hospitals at the Rohrbach and the J.F. Miller farms back across the Antietam. As the sun set on September 17, both sides settled in posting pickets in and around the Sherrick farm. Neither side renewed the battle on the 18th but there was substantial picket firing throughout the day. That evening the Confederates withdrew across the Potomac and Union forces moved into Sharpsburg. One young Union soldier, Private R.G. Carter of the 22nd Massachusetts Infantry wrote about the scene at the Sherrick house.

“the sun came out bright and beautiful … The enemy had now, it was soon discovered, left our front … Upon visiting Sherrick’s house this morning, we found it quite a sumptuous affair. It had been hastily evacuated, as it was between the lines. The foragers ahead of us had pulled out what edibles it contained, and among them a splendid assortment of jellies, preserves, etc., the pride of every Maryland woman’s heart, but now scattered all about. The orchard was filled with the choicest fruit. What a feast! Our stomachs just beginning to become accustomed to “salt horse” and “hard tack,” earnestly opened and yearned for this line of good things. No crowd of schoolboys, Let loose from the confinement of a recitation room, ever acted so absurdly, as did these rough, bronzed soldiers and recruit allies, on that death-strewn ground about Sherrick’s yard and orchard. They would seize a pot of jam, grape jelly, huckleberry stew, or pineapple preserve, and after capering about a while, with the most extravagant exhibitions of joy, would sit upon the ground, and with one piece of hard bread for a plate, and another for a scoop, would shovel out great heaps of the delectable stuff, which rapidly disappeared into their capacious mouths …

The buildings did not suffer much structural damage but the crops were ruined, and soldiers from both sides pillaged personal possessions. Joseph Sherrick claimed damage to his home of $8 from an artillery shell and $1,351 in damages from occupying Federal troops. According to a letter written by Jacob Miller in October 1862, the Otto and Sherrick farms were full of encamped troops. Miller noted that he had sown nine acres of wheat on his land and if not for the army’s presence, he would have been able to sow upwards of a hundred acres. The foraging of Union soldiers immediately after the battle caused more destruction to the Sherrick farm than the actual battle did. Although the Sherrick farm was not used as a hospital the fields and farmland became a burial ground for soldiers from both sides.

But the damage that the Sherrick farm received was nothing in comparison to their close friends, the Mumma family. Their house was deliberately set on fire by the Confederates and that fire bled to almost all the other buildings. Joseph opened the house up for Samuel and his family to reside until their home was rebuilt in June 1863.

By 1863, Joseph and his son-in-law Victor Newcomer were living in Funkstown about ten miles north of Sharpsburg. After the Mumma family moved back to their farm it is unsure who lived on the Sherrick farm. The property was most likely rented out to other tenant farmers. It’s also possible that in an attempt to recoup some of their financial losses the Sherrick’s sold some of their land holdings. That year following the battle, John Benner had been purchasing property from the Rohrbach family on the west side of the Antietam Creek. In 1866, Benner acquired 9 acres from Joseph and Sarah Sherrick for $730. A new farmstead was constructed there near the bridge and would be known as the Benner-Spong Farm.

Victor Newcomer continued to seek money for the damages long after Joseph died in 1871, but he received very little compensation from the Federal government. Joseph Sherrick, Jr. died on August 10, 1871. Almost three years to the day, Sarah passed away in 1874. Joseph and Sarah Sherrick are buried in the Mumma Cemetery, with Joseph’s parent and their friends the Mummas.

Over the next several decades the property remained in the Sherrick-Newcomer family, eventually being inherited by Anna Newcomer’s children, Frank S. Newcomer and Virginia S. Nicodemus. During this time, parcels were sold to both veteran’s associations and the Federal government for monument placements. In 1925 the property was purchased by James A. Dorsey. The property stayed in the Dorsey family until 1964 when the 186-acre Sherrick farm (known as the Dorsey tract) was sold to the National Park Service. The following year, as part of the Mission 66 project, work began on the Burnside Bridge Bypass Road. By redirecting local traffic past the Sherrick farm and off the bridge, the National Park Service was able to restore the bridge and complete an interpretive tour stop.

The Sherrick House remains as it was originally configured when it was build in 1835. The summer kitchen was restored and the stone walls have been rebuilt. Unfortunately the historic Sherrick barn was destroyed by fire in 1985, but the park service has been able to restore the foundation of the the barn. Today the farmstead is beautifully maintained by the National Park Service and you can hike the trails across the farmstead to the Burnside Bridge and walk the tour road around the Sherrick farm. Not only was the Sherrick Farmstead an eyewitness to the terrible fighting that occurred there, but it is a reminder of how the families of Antietam were connected for generations and how they survived the ordeal of war.

Sources:

-

Ancestry.com, Joseph Sherrick Family, Census Data 1850-1880. Retrieved from: https://www.ancestry.com\

-

Biscoe, Thomas Dwight and Walt Stanley. The view from the Conf. side of Antietam Creek near Burnside Bridge looks probably about North,. DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, 1884. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/civ/id/132/rec/25

-

Civil War Talk. Sherrick House at Antietam Interior Photographs/Tour Retrieved from: https://civilwartalk.com/threads/sherrick-house-at-antietam-interior-photographs-tour.158270/

-

Carter, Robert Goldthwaite Four brothers in blue; or, Sunshine and shadows of the War of the Rebellion; a story of the great civil war from Bull Run to Appomattox. Washington, Press of Gibson Bros., Inc., 1913. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/cu31924032780623/page/n283/mode/2up/search/Antietam

-

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, Antietam, Maryland. Battlefield near Sherrick’s house where the 79th N.Y. Vols. fought after they crossed the creek. Group of dead Confederates, MD. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/cwpb.01112/

-

Maryland Historical Trust, Sherrick House, WA-II-334, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, 1978.

-

Oehrlein & Associates Architects, Sherrick House Historic Structures Report. United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1995.

-

Reardon, Carol and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Antietam: experiencing the battlefield through history, places and people, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

-

Schmidt, Alann and Terry Barklery. September mourn: the Dunker Church of Antietam Battlefield, El Dorado Hill, CA: Savas Beatie LLC. 2018.Taggert, Thomas, Map of Washington County. L. McKee and C.G. Roberton, Hagerstown, Maryland 1859.

-

Summerfield, Mark. Sherrick House. Retrived from: http://msummerfieldimages.com/sherrick-farm/

-

U.S. National Park Service, Burnside Bridge Area Cultural Landscape Inventory, Antietam National Battlefield, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2016.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Burnside Bridge Area Cultural Landscape Report, Antietam National Battlefield, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2018.

-

Walker, Kevin M., Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape. Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

Wolfe, Robert and Janet. Robert and Janet Wolfe Genealogy – Joseph Sherk. Retrieved from: https://www-personal.umich.edu/~bobwolfe/gen/person/g5803.htm

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

These are beautiful photos. Joseph was my great great grandfasther. my grandfather Hall Sherrick and my father was his son Orville Sherrick my Name is Nellie may i.

Sherrick, this is a place on my bucket list to visit. I’m 75 and no time is running short. Thank you!!!!