We continue the story of the Farmsteads of Antietam with the Jacob Avey farm that sits at the southern edge of Sharpsburg. The D.R. Miller cornfield, the Poffenberger woods, and the Piper orchard; when we hear these the names of these places we know where they are on the Antietam battlefield and the action that occurred there. But very few people have heard of the Avey farm, know where it is or even understand what happened there. Like the copse of trees at Gettysburg for the Confederate High Water Mark, the Avey farm is the “High-Water Mark” for the Union at Antietam and is critical to understanding the Battle of Antietam.

In the early 1700’s very few people lived west of Frederick. To entice immigrants into western Maryland, land was being offered at very low prices; and people with disposable wealth began to purchase large tracts of land. In 1736, Joseph Chapline, Sr. moved west and began acquiring hundreds of acres of land along the Potomac River through grants and purchases. In 1747 he patented the 250-acre tract “Hunting the Hare,” located just south of present-day Sharpsburg. Earlier that year, Chapline also purchased an adjacent 150-acre tract originally patented by Francis Abston in 1742 known as “Abston’s Forrest.” When the French and Indian War erupted in 1754, Chapline was called upon to assist his friend and Maryland Governor, Horatio Sharpe. As a Captain, Chapline would help finance and build forts along the frontier.

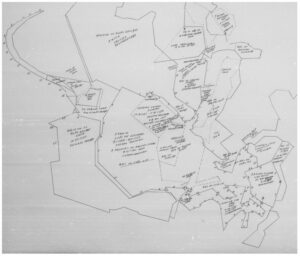

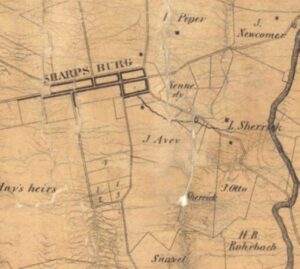

With the war over, Joseph Chapline sought to take advantage of the influx of new settlers coming into the valley. In 1763 Chapline founded the town of Sharps Burgh (present-day Sharpsburg) in honor of Maryland’s provincial governor Horatio Sharpe. This new town would be located on a 200-acre tract that Chapline had purchased known as “Hickory Tavern”. What made the “Hickory Tavern” tract such an appealing place for a town was the presence of a fresh water spring (Garrison’s Spring) and its location along the wagon road to Philadelphia. This parcel was located close to his plantation and adjacent to two other parcels he owned, “Resurvey on Abston’s Forest” and “Hunting the Hare.” In August 1764 Chapline patented “Joe’s Lot,” which consisted of 2,127 acres on the south and east sides of Sharpsburg. The parcel included over 1,680 acres of vacant land along with the original surveys of Resurvey on Abston’s Forest and Hickory Tavern.

Joseph Chapline died in 1769. In his will he divided his vast holdings among his children. His eldest, Joseph Chapline, Jr., received the majority of his lands, including Sharpsburg and the surrounding land. In 1789, Joseph Chapline, Jr., applied to the land office in Annapolis for a resurvey of his lands into a single tract he wished to be known as Mount Pleasant, and this patent for 2,575 acres was received on July 15, 1791. Over the next several years, the Chapline children and other land owners divided these large land tracts into smaller family sized farms and sold them to the settlers moving into the Sharpsburg area.

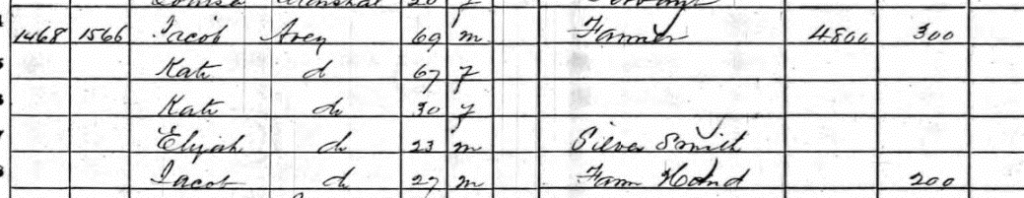

One of these families was the Avey or Eavey family. Henry Avey immigrated with his family to America in 1732 from Rotterdam. It is believed that the Avey’s were from the Berne, Switzerland area and were escaping religious persecution. The Avey’s landed in Philadelphia and by 1746, Henry Avey owned 200 acres of land in what is now Washington County, Maryland. Henry had three sons; John, Joseph and Jacob. The three brothers all assisted in the defense of the colonies during the French and Indian War. In 1783, Joseph purchased part of the track known as Spriggs Delight along the Potomac River near where Taylor’s Landing is today. It appears that Joseph’s son, Michael inherited his father property after he died in 1799. According to the 1803-04 Washington County tax record, Michael Avey owned 150 acres of Spriggs Delight. Michael’s oldest son, Jacob was born on May 12, 1791. Jacob was a farmer and in the 1820’s he began to purchase properties around the Sharpsburg area. Jacob would marry Catharine Palmer in January 1815 and together they would have ten children.

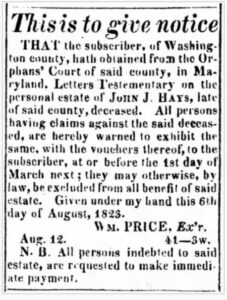

Here our story goes back to Joseph Chapline, Jr. He and his wife, Mary Ann had no children, but other family members filled their home at Mount Pleasant. Joseph’s nephew, Dr. John J. Hays was residing at Mount Pleasant and came into his favor. Just a few months before his death in 1821 Joseph Chapline Jr., sold 1,000 acres of Mount Pleasant, including the house, to his nephew and named Hayes the executor of the estate. Dr. Hayes also owned other properties in and around Sharpsburg. To settle the estate of his uncle, Hays held a public sale to sell farming equipment , livestock and household affects. Unfortunately, Dr. Hayes died shortly after Chapline in 1823. The executor of his estate was William Price. Not only did he have to settle John J. Hays’ estate, but now he also had the unfinished business of the Chapline estate. Within a matter of a few years the Hays and the Chapline estate was settled and most, if not all the property including Mount Pleasant and the land south of Sharpsburg was sold.

In October, 1826 Jacob Avey purchased 22 acres from the executors of the John J. Hays estate for $550. This property was just southeast of Sharpsburg near the Joseph Reel mill (this property was sold in 1831). Two years later in September 1828, Jacob purchased another property from the John J. Hays estate for $500. This was an 86 3/4 acre farm known as the Bower Farm adjacent to Sharpsburg between the road to the Antietam Iron Works (the Harpers Ferry Road today) and the Reel Mill road (the Burnside Bridge Road today). Jacob may have owned more land, but those records have not been found. Over the next 30 plus years, Jacob and Catharine Avey raised their family on this farmstead at the edge of Sharpsburg. According to the 1860 census, the Avey farm was valued at $4,800 with $300 in personal property and three of their adult children still resided at home.

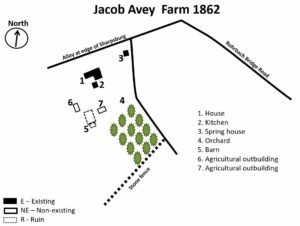

The Avey house is a two-story ell shaped dwelling with brick and frame construction. Just to the back of the house is a board and batten out kitchen with stone chimney and to the east of the house near the road leading out of Sharpsburg is a stone springhouse. South of the house was a large Swisser bank barn and a number of other out buildings and dependencies. Today only the ruins of the barn still exist.

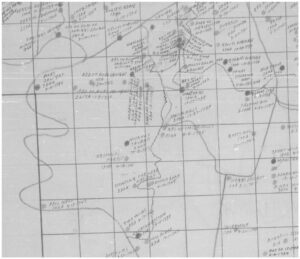

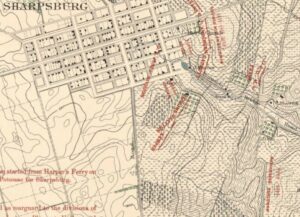

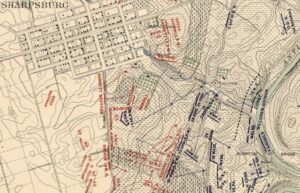

On September 15, 1862 Confederate forces under General Robert E. Lee were withdrawing back toward the Potomac River after their defeat at South Mountain. Receiving word from General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, that the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry was going to surrender, Lee decided to consolidate his army at Sharpsburg using the high ground east of town to position his defensive line. Throughout the day Confederate soldiers from David R. Jones’ division moved into Sharpsburg and onto the Avey farm. D.R. Jones was responsible for the center and southern end of Lee’s line. Jones stretched his small division from the Boonsboro Pike at Cemetery Hill to the Rohrbach Bridge road with two brigades and five artillery batteries; across the road the brigades of Walker, Drayton, and Kemper covered the raise across the Avey farm. Between the Avey house and their orchard, Captain Hugh R. Garden’s four gun battery was parked. To his front, Jones positioned Robert Tombs’ brigade to cover the Rohrbach Bridge with three batteries of artillery for support and part of Nathen Evan’s brigade was forward on the Joseph Sherrick farm. Later the next day, the division of John Walker arrived to Jones’ left to cover the flank and the Snavely’s Ford on the Antietam.

With an impending battle on their doorstep, the Avey’s most likely packed up some of their belongs and left their home. It is possible that Jacob’s family went to stay with their son Samuel, daughter in law Kate, and their 5 children in Porterstown just east of the Antietam Creek. Their son, Jacob (named after his grandfather) who was 12 yrs old at the time, remembered “sitting on a fence beside the road, watching the soldiers striding down South Mountain” on their way to toward Sharpsburg. When fighting began on the 17th, young Jacob was standing near the smokehouse when “a Rebel shell tore through and wrecked the building but spared his life“.

That Rebel shell most likely came from the artillery D.R. Jones had posted on the heights at the edge of Sharpsburg. According to his battle report, “Daylight of September 17 gave the signal for a terrific cannonade. The battle raged with intensity on the left and center, but the heavy masses in my front–repulsed again and again in their attempts to force the passage of the bridge by the two regiments before named, comprising 403 men, assisted by artillery I had placed in position on the heights–were unable to effect a crossing”. Throughout most of the morning the fighting was raging north of D.R. Jones’ position. Early into the battle Lee directed John Walker’s division to move to the north of Sharpsburg to support General Jackson’s command near the Dunker Church. General Daniel H. Hill was directed to shift his defense to the north as well and Jones was ordered to send G.T. Anderson’s brigade to support General Hood. Around 10am the Union Ninth Corps began attempts to force a crossing over the Antietam at the Rohrbach Bridge and the ford. By 1:00pm the Union forces had taken the bridge and were crossing over Snavely’s Ford as well. General James Longstreet said, “Brigadier-General Toombs held the bridge and defended it most gallantly, driving back repeated attacks, and only yielded it after the forces brought against him became overwhelming and threatened his flank and rear”.

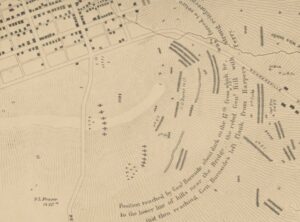

This redeployment of forces to the north and the loss of the bridge and ford forced Jones to realign his small division in order to defend the Confederate right. Garnett’s brigade was left to guard Cemetery Hill. Walker’s brigade and Garden’s battery moved to the left of the Avey farm to watch the draw up into Sharpsburg along the Rohrbach Bridge Road. Captain James S. Brown, in command the four guns of the Wise (VA) Battery redeployed from the Otto farm to the hill at the edge of the stone fence on the Avey farm along with a couple of guns from Capt. James Reilly’s battery. Kemper and Drayton moved their brigades forward to the fence at the hill to await the impending Union advance. John Dooley of the 1st Virginia Infantry recalled, “We are moved to meet this attack almost between the advancing enemy and the town of Sharpsburg. A few of our men are in the orchard afore mentioned, and behind a stone wall, and the majority behind a rail fence on the borders of a cornfield. Two pieces of artillery are all that can be spared to keep the enemy back”. The Confederate artillery on the Avey farm was taking it’s toll on the Union infantry trying to move upon the Rebels along the fence line.

By 3:00pm, Burnside’s Ninth Corps was in position to begin their assault toward Sharpsburg. Colonel Harrison Fairchild, a brigade commander in General Isaac Rodman’s division wrote, “We continued to advance to the opposite hill under a tremendous fire from the enemy’s batteries up steep embankments. Arriving near a stone fence, the enemy – a brigade composed of South Carolina and Georgia regiments – opened on us with musketry. After returning their fire, I immediately ordered a charge, which the whole brigade gallantly responded to, moving with alacrity and steadiness. Arriving at the fence, behind which the enemy were awaiting us, receiving their fire, losing large numbers of our men, we charged over the fence, dislodging them and driving them from their position down the hill toward the village,”.

Next to the New York brigade on their left flank was the lone 8th Connecticut Regiment, advancing toward the Harpers Ferry Road. As the Fairchild’s New Yorkers were reaching the heights, Orlando Willcox’s Union Division advanced astride the Rohrbach Bridge Road. His left brigade under the command of Colonel Thomas Welsh advanced across the Avey fields and pushed into the orchard. Col. Welsh reported, “I moved my whole command over a steep hill, immediately charging the enemy and driving them rapidly in the direction of Sharpsburg, my troops advancing to the edge of the town and capturing the rebel Captain Twiggs and several soldiers”. Welsh was referring to two of his regiments, the 8th Michigan and the 100th Pennsylvania that had driven the Rebels out of the orchard and to the outskirts of Sharpsburg.

The Confederate line was breaking, Fairchild’s men could see the spires of town. Dooley remembered, “The Yankees, finding no batteries opposing them, approach closer and closer, cowering down as near to the ground as possible, while we keep up a pretty warm fire by file upon them as they advance. Now they are at the last elevation of rising ground and whenever a head is raised we fire. Now they rise up and make a charge for our fence. Hastily emptying our muskets into their lines, we fled back through the cornfield.” Just as the end seemed to be in sight for the Union forces advancing across the Avey farm, Confederate brigades from General A.P. Hill’s division arrived on the left flank of the Ninth Corps. A.P. Hill’s sudden arrival on the Union left forced them to withdraw from the Avey farm back to the Sherrick and Otto farms where they began their advance.

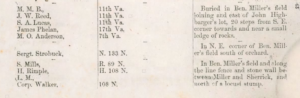

Although there was no major fighting on September 18, sporadic gun fire occurred across the fields on the southern end of the lines as both sides tended to the wounded and began to bury their dead. The Confederates buried about a dozen men on the Avey farm. The Union would have to wait until the 19th, after the Rebels withdrew back across the Potomac for their burial details to begin the dating task of burying the almost 200 dead Union soldiers across the Avey farm.

Like many of their neighbors around Sharpsburg, when the Aveys returned home they found death, destruction and devastation. Across their fields lay the dead from both sides, with guns and equipment scattered about. Most of the split rail fencing was gone, their cornfield was trampled down, and hay was either used for the wounded or fed to the horses. An initial appraisal of the damage totaled over $1000 which included $75 for house damaged, $72.75 for furniture, and $20 for a damaged carriage. Of course the Federal government was not going to paid any damage directly related to the combat that took place.

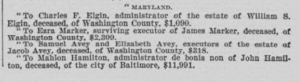

However a later claim had been filed for the fencing and forage used or taken from the farm in the amount of $477.95, but it would take until 1902 for the government to find the the claim was justified. In 1905. the reparations were paid in the amount of $318 to the executors of the estate, Samuel and Elizabeth Avey.

Just over a year after the battle, Jacob Avey died on October 12, 1863 at the age of 72 and Catharine died on July 14, 1870. Although they are both buried in the Methodist Cemetery in Sharpsburg only Catharine’s head stone still remains.

Four years after Jacob died, Catharine and the children sold the 86 3/4 acre farm to John Ecker in 1867. John Ecker’s daughter married a Benjamin Miller and it is believed that they lived on the farm. The reasoning for this is when the Bowie List of the Burial Places of the Remains of Confederate Soldiers was completed in 1868 it indicted Confederates had been buried on the Ben Miller farm referring to locations near the Sherrick farm and the John Highbarger lot at the edge of Sharpsburg. Further evidence of this is that the farm was sold to William Thomas in 1876 and this is indicted on the 1877 map of Sharpsburg.

At some point before the turn of the century the spelling of the Avey name had changed to Eavey. Four of the ten Avey children (Jacob and Catharine) would move west, settling in Illinois and Nebraska, while the rest remained a little closer to home. Their son, Jacob stayed in Sharpsburg and married Elizabeth Marker. They would have a son named John Wesley Eavey who would become a prominent Sharpsburg figure. John Wesley Eavey was the principal of the Sharpsburg school where he taught for over twenty years, he served as president of the Sharpsburg Bank, and was a member of a number of local organizations.

In October 1894, veterans of the 8th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment had returned to Sharpsburg to dedicate a monument on the ground where they had fought. Earlier that year, a small plot of ground near the stone wall was purchased from John Otto, who now owned the Avey farm, for the placement of the 8th Connecticut’s monument. The War Department has also placed a mortuary cannon on the ridge to indict where Union Brigadier General Isaac Rodman was mortally wounded during the battle. Three years later on Memorial Day 1897, members of the 9th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment returned to dedicate their monument on a plot next to the 8th Connecticut’s monument. The 9th New York (Hawkins Zouaves) Monument stands at the “High Water Mark” of the Union final attack at Antietam.

After changing ownership a half a dozen times, it appears that in the 1940’s small parcels of the farm were sold off along the Harpers Ferry Road and High Street. The same is true for a handful of lots along the Burnside Bridge Road. Over the years, the northern section of the farm was not being cultivated and trees began to take over and the orchard was cut down. In 1976, Stephen Whilden had acquired the farm and parceled off 20 acres of the property that included the original farmstead and structures near the town of Sharpsburg. This property was purchased by Robert Stransky, the current owner of the Avey farmstead. When the Stransky’s took ownership of the farmstead, only the house, out kitchen and springhouse remained. The Avey farm remains private property, but it is a critical piece to understanding the Battle of Antietam and is an eyewitness to history.

*We are very grateful to Linda Irvin-Craig for taking the time to talk with us about the history of the Avey/Eavey family and sharing the information about her ancestors. We also want to thank Mr. Robert Stransky for allowing us to visit him at the Avey farm (Thanks to Dr. Tom Clemens for arranging the visit).

Sources:

- Ancestry.com, Jacob Avey Family, Census Data 1840-1940. Retrieved from: https://www.ancestry.com\.

- Avey, Michael Garland, The Cultural Resources of the Avey Family Phase 1, Dept. of Archeology, Pierce College, Fort Steilacoom, WA, 1986. https://archive.org/details/TheCulturalResourcesOfTheAveyFamilyPhase1

- Beeler, Ed and Michael J. Chapline, Searching for Joseph Chapline Maryland Frontiersman and Founder of Sharpsburg, Maryland, 2013

- Cowie, Steven When Hell Came to Sharpsburg: The Battle of Antietam and Its Impact on the Civilians Who Called It Home. Savas Beatie, El Dorado Hills, CA 2022.

- Irvin-Craig, Linda. Personal interview. May, 2021.

- Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. (1864). Map of the battlefield of Antietam Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/185f8270-0834-0136-3daa-6d29ad33124f

- Maryland – Antietam Battle Field, Airscapes. Sharpsburg, MD New York Monument in Foreground. Record Group 18 National Archives, College Park, MD. 1930 Retrieved from: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/23940817

- Maryland. Board of Trustees of the Antietam National Cemetery, and 1869-1873 (Oden Bowie) Maryland. Governor. A Descriptive List of the Burial Places of the Remains of Confederate Soldiers: Who Fell In the Battles of Antietam, South Mountain, Monocacy, And Other Points In Washington And Frederick Counties, In the State of Maryland. Hagerstown, Md.: “Free press” print, 1868.

- Maryland State Archives. Maryland Land Records On-Line, Washington County, April 25, 2021. https://mdlandrec.net/main/dsp_search.cfm?cid=WA.

- Maryland Historical Trust, Avey-Stransky House, WA-II-151, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, 1977.

- Nelson, John N. “As Grain Fall Before the Reaper”, The Federal Hospital Sites and Identified Federal Casualties at Antietam. Hagerstown, MD. 2004.

- Recker, Stephen J. Rare Images of Antietam: And the Photographers Who Took Them. Another Software Miracle; Sharpsburg, Maryland 2012.

- Recker, Stephen J. Virtual Antietam; Final Attack Trail. Retrieved from http://www.virtualantietam.com/sites/default/files/field/image/1897_9thNYmonDed.jpg.

- Schildt, John W. Monuments at Antietam. E Graphics, Brunswick, MD 2019.

- Taggert, Thomas, Map of Washington County. L. McKee and C.G. Roberton, Hagerstown, Maryland 1859.

- The Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland) Jacob Eavey Obituary, 16 Aug 1948. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/

- The Touch Light and Public Advertiser (Hagerstown, Maryland) Estate of John J. Hays deceased, 28 August 1823. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/

- Tracey, Dr. Arthur G. “Land Patents of Washington County, MD. Showing their location on the land-their adjoining tracts- the relationship one to another-plus other related information“. MDLANDREC. Maryland Historic Trust. Retrieved from http://mdhistory.msa.maryland.gov/tracey_fr_wa_cr/html/index.html

- Washington Historical Trust, Architectural & Historic Treasures: 43 – Stone Hill circa 1800-1825, North of Sharpsburg, MD. Hagerstown, Maryland February 7, 1993. Retrieved from http://washingtoncountyhistoricaltrust.org/3-stone-hill-circa-1800-1825-north-of-sharpsburg-md/.

- Washington Historical Trust, Architectural & Historic Treasures: 113 – Mount Pleasant, circa 1790, Sharpsburg, MD. Hagerstown, Maryland September 7, 1997. Retrieved from http://washingtoncountyhistoricaltrust.org/136-mount-pleasant-circa-1790-sharpsburg-md/.

- Western Maryland’s Historical Library. Washington County, Maryland, Taxes 1803 Lower Anteatum Hundred, Washington County, Maryland, 1803 https://digital.whilbr.org/digital/collection/p16715coll46/id/82/rec/11.

- U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

- United States Congressional Serial Set. Court of Claims for Jacob Avey, 1902.. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/books/edition/United_States_Congressional_Serial_Set/iA1HAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&kptab=editions

Thank you for researching and writing these Antietam farmstead articles. I have read and enjoyed each of them. I hope when you finish them you publish them in a book.

Thank you. We’re glad you enjoy them. We hope that one day we’ll be able to put them into a book as well.

This was my papa’s farm! I grew up here. Bob Stransky was my grandfather. He passed away last year. Thank you for writing this! It is very interesting to find out the history behind his property.

Thank you for your kind words. In doing the research on the Avey farm, I had the pleasure of speaking with you grandfather. Very nice man and was sorry to hear of his passing. Everyone in Sharpsburg loves his dog Buddy.

Enjoyed reading this. John Wesley Eavey was my grandfather and Linda Craig is my first cousin. She has done a lot of work on our ancestry.

I loved my time spent in Sharpsburg and have always been interested in the history.