The John Otto farm is the last farmstead on the battlefield and is often overlooked as you drive to the Burnside Bridge. Although the main house is the only period structure still standing on the property, the Otto farm is full of history.

In 1763, Joseph Chapline, Sr., founded the town of Sharpsburg. Upon his death in 1769, his sons inherited much of his property in the area. In 1789, Joseph Chapline, Jr., applied to the land office in Annapolis for a resurvey of his lands into a single tract. This 2,575 acres became known as Mount Pleasant. With the migration into Western Maryland in the 1790’s, Joseph Jr., began to sell off some of this land.

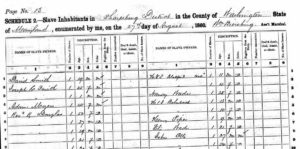

In 1815, Joseph, Jr. conveyed a portion of Mount Pleasant to Peter Ham, about 133 acres. Ham lived in Sharpsburg and operated a tannery. “When Ham died in 1819, he willed all his property except the tanyard, to his wife Margaret”. According to an 1828 advertisement the property was placed for public sale and it described the farm as “A Valuable Plantation, containing about 145 acres of first rate Limestone Land, with common improvements and a never-failing spring thereon .. ,” The farm never sold so in 1831, Mrs. Ham sold half of the estate, 66 acres, to Joseph Sherrick and the other half to John Otto.

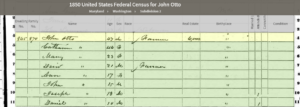

John Otto was the son of John David Otto who emigrated from Hanover, Germany in 1795. After landing in Philadelphia, he remained there for about eighteen months learning the trade of a tailor. John David Otto moved to Sharpsburg “and opened a tailor shop in a small building near the Reformed Church”. After moving to Sharpsburg he married Maria Catherine Bowlus with whom they had two children: Elizabeth and John. John was born on November 25, 1802. As a young man, John worked as a farm hand and sometimes in his father’s tailor shop.

In 1825, John married Dorcas Miller and they lived on a small farm outside of Sharpsburg. John and Dorcas would have six children together: Mary Ann, David, Ann Catherine, John, Joseph, and Daniel. To make room for their growing family John purchased the property from the widow Ham in 1831.

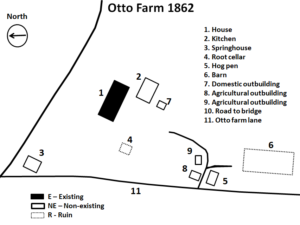

Over the next several years John and Dorcas worked to turn the property into a thriving farmstead. John built a substantial two-story frame dwelling with clapboard sliding and a stone cellar foundation. Near the house was an orchard containing apple, pear and cherry trees.

Back of house

Down the hill from the house near the Rohrbach Bridge Road, a spring-house was built over the ‘never-failing spring’. Just to the rear of the main house, the Otto’s constructed a large log kitchen and a root cellar was built into the hill where the cool temperatures provided storage of vegetables. Further up the hill from the house was the large Pennsylvania style bank barn. A hog pen and various other outbuildings and dependencies surrounded the farm as well. Across from the farm, post-and-rail and worm fences divided the fields and along the bridge road was a well-constructed stone wall.

In 1845, Dorcas passed away from unknown causes. John would remarry in 1849 to Catherine Gardenour, who was born on the old Belinda Spring farm, on the Antietam Creek. John became a successful farmer and “By 1862 he owned and cultivated three farms, including his 66-acre home farm, totaling over 300 acres, with over 500 head of cattle” which was a large number of livestock for the time. According to the county records in 1860, “John Otto’s farm was valued at $4,000, and his livestock was valued at $500. In the year ending June 1, 1860, the farm produced 800 bushels of wheat, 100 bushels of rye, 400 bushels of Indian corn, 70 pounds of wool, 20 bushels of potatoes, $25 of orchard products, 500 pounds of butter, 15 tons of hay, and 12 bushels of clover seed”.

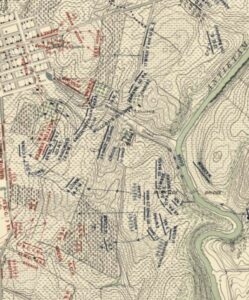

By mid-September 1862, the winds of war swirled around the Antietam Valley as Confederate soldiers from Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began to consolidate around Sharpsburg. To the southeast of town on the Otto farm, Georgians from Brigadier General Robert Toomb’s brigade were positioned on the bluffs overlooking the Rohrbach Bridge and along the Antietam Creek. Before long, hungry Confederates came looking for food. According to Hilary Watson, “the Rebels came in hyar, and the hill at our place was covered with ’em. They’d walk right into the house and say, ‘have you got anything to eat?’ like they was half starved.” Hilary’s mother and the Otto’s provided them some bread, bacon, and milk. The next morning, Mr. Otto took his family and Aunt Nancy away to safety. We’re not sure where they went to, maybe to relatives but young Hilary remained behind.

The next day the fighting along the Antietam Creek began about mid-morning. Confederate artillery batteries positioned on the heights across the fields south of the farm. Soon after noon, the Union IX Corps took control of the Rohrbach Bridge forcing the Confederates to pull back to the heights outside of Sharpsburg. It took almost two hours, for the Union forces to reorganize and move into position to began their advance. At approximately 3PM, the IX Corps attack began. Colonel Thomas Welsh’s brigade advanced through the Otto farmstead with Issac Rodman’s Division on the left flank. Two Union artillery batteries moved into the position vacated by the Rebel guns. As the Union pushed the Confederates beyond the farmstead toward Sharpsburg, other Union brigades advanced across the Otto farm in support. Just as the objective seemed within sight for this final Union attack, Confederate General A.P. Hill’s Light Division arrived on the field. Hill’s men drove the Union forces back to the Otto farm where the battle would end as darkness fell.

Of course after the battle the Otto farm like so many others was used as a hospital. John Otto would write, “My House, Barn, and Granary were taken possession of September 17th and used for Hospital purposes til the 4th of Nov. 1862, during which time everything in and around it that could be of any service, was taken and used, including Beds, Furniture, Commissary stores, condiments and anything that would contribute to the comfort of the wounded, being either consumed entirely or rendered unfit for further use. The surgeons in charge at my house was I think, Dr. Warren and Dr. McDonald.” One Union soldier, William Mitchel of the 9th New York had engraved his name and unit in a windowsill in an upstairs bedroom of the Otto house. In 1873, Otto filed a claim for $2350.60, he would only receive $893.85 for his losses.

In 1864, after slavery was abolished in Maryland, Hilary Watson continued to work on the Otto farm as a hired laborer. John Otto paid $300 when Hilary was drafted to serve in the Union Army in order to keep him on the farm. Years later, Hilary and his wife Christina would buy a lot on East High Street in Sharpsburg near Tolson’s Chapel, and build a house there. Together they helped build the African American community in Sharpsburg in the post war years. Both Christina and Hilary Watson are buried in the Tolson’s Chapel Cemetery.

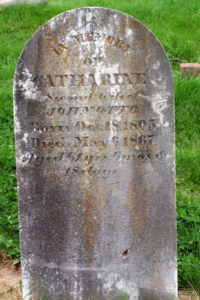

Following the war John Otto retired from farming leaving the the tending of the farm to his son. He moved into Sharpsburg where his second wife, Catherine died in 1867. After her death, he made his home with his son David on Antietam Street. John died on December 8, 1884. John and both his wives, are buried in the Mount Cavalry Lutheran Cemetery in Sharpsburg.

In 187o, the Otto’s sold the 66-acre property to Jacob B. Stine. Stine would acquire the other half of the original farm in 1891 and then sold the whole 131 acres to James and Susan Dorsey in 1908. The property remained in the Dorsey family until 1968, when the farmland was sold to Paul and Twila Shade. In 1971, the Dorsey’s sold the 2+ acres containing the Otto buildings to Charles and Orpha Mae Kauffman who would in turn sell it to the National Park Foundation five years later. In 1984, the National Park Service purchased the 2+ acres from the foundation and in 2003 the remaining parcels of the Otto farm and the Sherrick farmland were acquired by the National Park Service from the Shade estate.

Today, the farmland has been turned into grassland for wildlife and a habit for migrating Monarch butterflies. Although only the main house and some ruins are all that remains of the Otto farmstead, it continues to be an eyewitness to a unique history of the Farmsteads of Antietam.

Sources:

-

Ancestry.com, John Otto Family, Census Data 1850-1880. Retrieved from: https://www.ancestry.com\

-

Banks, John, John Banks Civil War Blog retrieved from: http://john-banks.blogspot.com/2013/05/antietam-panorama-ruins-of-john-ottos.html

-

Biscoe, Thomas Dwight and Walt Stanley. The view from the Conf. side of Antietam Creek near Burnside Bridge looks probably about North,. DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, 1884. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/civ/id/132/rec/25

-

National Park Service, Antietam National Battlefield Survey Report, Paula S. Reed and Associates, Inc., Hagerstown, MD. Form, 10-900. 1999.

-

Nelson, John H., As Grain Falls Before the Reaper: The Federal Hospital Sites and Identified Federal Casualties at Antietam, Hagerstown: John H. Nelson, 2004

-

Reardon, Carol and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Antietam: experiencing the battlefield through history, places and people, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

-

Schmidt, Alann and Terry Barklery. September mourn: the Dunker Church of Antietam Battlefield, El Dorado Hill, CA: Savas Beatie LLC. 2018.Taggert, Thomas, Map of Washington County. L. McKee and C.G. Roberton, Hagerstown, Maryland 1859.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Hilary and Christina Watson. Retrieved from: https://www.nps.gov/people/hilary-and-christina-watson.htm

-

U.S. National Park Service, Burnside Bridge Area Cultural Landscape Inventory, Antietam National Battlefield, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2016.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Burnside Bridge Area Cultural Landscape Report, Antietam National Battlefield, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2018.

-

Walker, Kevin M., Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape. Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

Leave A Comment