While traveling on the roads running through the battlefield you can see most of the farmsteads at Antietam except for one – the Joseph Parks farm. In order to see this farm, visitors have to walk out the Three Farms Trail from the Newcomer House. Although the land had been cultivated for more than 100 years before the battle, in 1862 the house and farm were fairly new. Originally part of James Smith’s property and patented “Smiths Hills”, this 160 acres is known today as the Joseph Parks Farm.

In 1739, James Smith, a planter from Prince George’s County received a patent of 208 acres. It’s believed that Smith lived in the area, as he was surveying lands in the future Frederick and Washington counties and was an attorney for the Frederick courts. Over the next fifteen years, Smith continued to add land to his holdings. In 1754, Smith surveyed 12 acres of Porto Santo, another nearby patent. In 1756, a “Resurvey of Smiths Hills” was done adding 302 acres for a total of 510 acres and a Resurvey of Porto Santo was done to correct several errors which increased its size to 23 acres. During the resurvey it was found that the Porto Santo “included ‘improvements’ of one acre of cleared land, 400 fence rails and a log house”. Smith’s holding of these two patents would become the properties of what we know today as the Newcomer and Park Farmsteads.

Knowing that colonial interest and the French and Indian War led to more permanent inroads into the backcountry, Smith petitioned Frederick County in 1755 for the building of both a ford across the Antietam Creek and a new road, because he intended to build a mill along the creek on his land. Smith also knew that an improved roadway through his property would not only increase the value of his land but that of the surrounding area. Although Smith did not build a mill, “he had set the groundwork for the future development of the milling industry on the property” and a new road would eventually be built from Red Hill to Swearingen’s Ferry on the Potomac at Shepherdstown.

As the French and Indian War was ending, Christian Orndorff, a millwright from Lancaster County, arrived in the area in 1762. Now that the region was safe and open for settlement, Orndorff was looking for a suitable site to build a grist mill, and he found it along the Antietam Creek. Christian Orndorff purchased 503 acres of Resurvey on Smiths Hills and 11 acres of the Porto Santo.

Over the next thirty years the Orndorff family turned the property into a substantial industrial complex. In addition to a large house and barn, there was a grist mill, a saw mill and a workshop near the Antietam Creek. The mills were powered by water diverted from the creek through a mill race that Orndorff built. They also farmed crops of wheat and corn and later established a plaster mill, a cooper shop and other tooling shops.

In 1796, the Orndorff’s sold 324 1/4 acres for £5500 to Jacob Mumma. This purchase included portions of several patents, but 303 acres were part of the Resurvey of Smiths Hills. The Mummas had arrived in Philadelphia in 1732 and settled in Lancaster County. Like other Germans settling in the area, the Mumma family traveled down the Wagon Road to Sharpsburg. They were accompanied by Joseph Sherrick, Sr. and his family. Sherrick would also purchase property along the Antietam from the Orndorff’s.

Photograph taken on Sept. 22, 1862, by Alexander Gardner’s assistant, James F. Gibson. The Parks Farmstead can be seen in the upper right hand corner. (LOC)

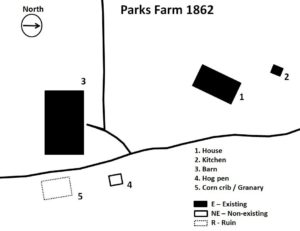

Jacob Mumma and his sons continued to run the mill and farming operations. Over the next several years Mumma would acquire “two-thirds of the large land tract amassed by the Orndorff family decades earlier”. This area incorporated what is known today as the Mumma Farm, Newcomer Farm and the Parks Farm. In 1831, Jacob Mumma and his wife Elizabeth transferred ownership of the mill property to their son John. Around this time, it is believed that a house and barn were constructed just north of the mill along the creek for John’s eldest son – Elias Mumma. This became known as the “lower farm”, the future Parks farmstead. Business at the Mumma mill was booming, but John Mumma died suddenly in 1835 and without a will. His father, Jacob purchased the property back from John’s estate and resold the mill and farm to his younger son, Samuel in 1837.

Samuel and his wife had been living at the house on the Mumma Farmstead, but they moved back to the mill complex and continued the operations of the mill and farm. Samuel sold 151 acres of the mill complex portion of the property to Jacob and John Emmert in 1841 to pay off debts, but he retained 190 acres of the “lower farm”. By 1843, Samuel was forced to put the “lower farm” into a Deed of Trust to pay off other creditors.

In 1850, the property was returned to Samuel Mumma by the trustees and it believed that Samuel’s son, Jacob H. Mumma was living on the farm as a tenant at this time. According to the 1860 census, Jacob had moved to Boonsboro and the farm was tenanted by a Jacob Myers (Meyer). In 1861, Samuel Mumma sold the “lower farm” for $10,500 to Phillip Pry who renamed the 166 acre property the “Bunker Hill Farm”. Phillip and his brother Samuel already owned a large amount of land north of the Bunker Hill Farm along the Antietam Creek, including a large grist mill. Phillip and his family continued to live at his farm just across the Antietam but rented the Bunker Hill Farm to a tenant named Joseph Parks and his family.

Parks had owned a house in Porterstown which was just on the other side of the creek. According to the 1850 census he lived there with his wife, Mary and their young children Rosean, Elizabeth, Mary and Martha. His wife Mary would pass away in 1855 and shortly after that Joseph married Aletha Ann Harmon and they would have six more children together.

On the morning of September 15, 1862, as they withdrew from the Battle of South Mountain, Confederate soldiers marched along the turnpike and across the Antietam toward Sharpsburg. General Robert E. Lee had decided to make a stand along the Antietam Creek to consolidate his divided army. Later that day as the Union army advanced to the east side of the Antietam Creek, the Bunker Hill Farm and the Parks family stood between the two warring parties.

The next morning, three companies of Federal troops crossed the bridge and deployed across the Newcomer property, securing the bridge as a future crossing point for the next day’s battle. Throughout the day the Bunker Hill Farm was in the center of a cannonade between the Union artillery on the east side of the Antietam and the Confederate guns along the ridge east of Sharpsburg. It is not known where the Parks went during the battle, but most certainly they departed like their neighbors, to the safety of friends or relatives in the area.

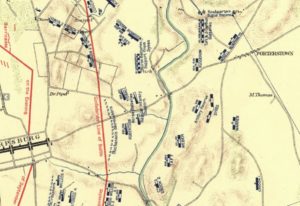

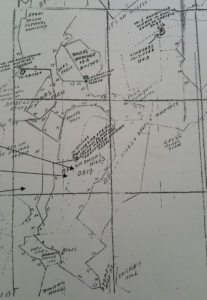

The next morning on September 17, as the battle raged to the north of Sharpsburg, more Union forces were sent across the Pry Mill ford just north of the Parks farm. Two divisions of the Second Army Corps moved west toward the East Woods and then pushed into the West Woods and southward across the Mumma and Roulette farms. About an hour later Major General Israel Richardson’s division crossed the creek just below Phillip Pry’s house and marched toward the Neikirk and Kennedy Farms before turning toward the fighting in the Sunken Road. Brig. Gen. John Caldwell’s brigade marched in a line of battle across the upper fields of the Parks farm before shifting to the right to support Gen. Meagher’s Irish Brigade.

Once the Confederates were driven out of the Sunken Road, Union artillery arrived to help hold the line along the high ground of the Parks farm and the Newcomer fields.

Although no specific source has identified the Parks farm as a field hospital, it seems likely that the 5th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry Regiment of Caldwell’s brigade would have used it as a temporary one. Col. Edward Cross, the commander of the 5th New Hampshire reported the situation of his surgeon, Dr. William Child and described the conditions of the battlefield hospitals, “The barns and sheds in all this region were occupied as hospitals by the Union army, and many Confederate wounded were retained here, and I believe were as well cared for as the Union Men. The barns were filled with flies, and wounds were sure to gather maggots about the dressings and even within the raw surfaces. To avoid this disgusting evil Assistant Surgeon Child personally gathered a few scores of shelter tents left on the battle-field, brought them to a suitable location, and with them built very comfortable hospital quarters and into them moved all the wounded of the Fifth, where they remained until able to be sent to Frederick city or were sent to Antietam hospital, which was finally established upon the western borders of the battle-field. Child was detailed for service in this Antietam field hospital, where he remained until about December 10…”

There are no known damage claims submitted by Joseph Parks, but several were submitted by Phillip Pry starting in 1865 and another in 1872. It is believed that the Quartermaster claim was for his home farm only and not the “lower farm’ or Bunker Hill Farm.

Union artillery and infantry units go into position on the evening of Sept. 17, 1862 across the Park farm

Although Phillip Pry received some payment, his claims became bogged down in legal proceedings and in 1874 he sold the remainder of his property and moved his family to Tennessee. During the investigation into Pry’s claim it was uncovered by Agent Sallade about Pry’s Bunker Hill farm and he reported, “Mr Pry owned two farms, one the [“Home”] farm containing 170 acres, and one the “Bunker Hill” farm of 166 acres separated by the Antietam Creek, and 1/2 mile apart… all his fencing was burned, his corn and wheat fed, together with a large quantity of hay… His wheat I find was cut in 1862, and put in 4 large stacks, some was in the barn. These stacks contained not less than 800 bushels this quantity was arrived at by the number of loads – 40 – averaging 20 bushels per load, placed in the stacks. Messrs Joseph Parks, Henry Gettmacher and Wm. Lantz who cut, hauled, and put up this wheat fully confirm this fact. The Affidants of other parties, neighbors and ex-soldiers also confirm this, and also that a portion of the wheat in the barn was used. Mr. Pry lost about 150 bushels on the farm across the Antietam Creek. Mr. Pry fully sets this forth in his affidavit”.

According to records, a few years after the battle Joseph Parks had “to mortgage his household furniture and personal belongings against a debt that he owed to Phillip Pry” most likely for the tenancy. Joseph Parks had moved several miles north of Sharpsburg, probably to Fairplay or Hagerstown, and became a full time shoemaker. He died in 1891 and is buried in Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown along with his second wife Aletha.

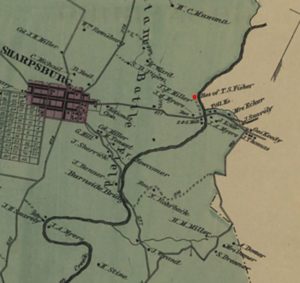

The 1877 Illustrated Atlas of Washington County, Maryland, District 1, Sharpsburg. The red dot shows the J. F. Miller properties

In 1867 Bunker Hill Farm was sold to Jacob F. Miller. Jacob Miller’s son, Otho H. Miller was living at the farm according to the 1870 census. During this time “a gabled dormer was added to the forebay of the barn most likely to accommodate improved threshing machines” and a second story was added to the north section of the main house.

In 1884, Jacob Miller sold the Bunker Hill farm to Henry and Laura Rohrer. The Rohrer family would operate the farm for the next 76 years. According to the 1910 census, their son-in-law Harry O. Clipp, his wife Stella and their two daughters, Ruth and Edna were living at the farm. Harry Clipp’s occupation was listed as a “House Carpenter” and he may have been the one who made improvements on the farm. During the Rohrer’s time at the farm a tenant house is built around 1905 and a corn crib / wagon shed was added onto the barn along with some other out buildings. In 1914, Henry Rohrer died leaving the farm to his wife Laura, who died in 1919. The farm was then transferred to her daughter and son-in-law.

The Clipp’s continued to make improvements to the farm, shifting their operation to dairy farming with a

concrete milking area added. Ruth Clipp and Edna (Clipp) Dorsey who inherited the farm from their parents, sold the farm to William Cunningham in 1960. In 1988, Cunningham sold the farm to the National Park Service with a life estate for himself.

After the death of Mr. Cunningham in 2000, the Park Service removed post-war out buildings including the tenant house, repaired the log out-kitchen, restored the barn, stabilized the farm house and recently replaced the roof on the house. A new recreational trail, the Three Farms Trail was created in 2006 that connects the Parks Farmstead to the Roulette Farmstead and the Newcomer Farmstead.

The Parks Farmstead is a another eyewitness to the history of the battle and the families that lived in the Antietam Valley.

Sources:

-

Find A Grave, Joseph Parks and family, Retrieved from: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49395745/joseph-parks

-

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, Antietam, Md. Another view of Antietam bridge. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/cwpb.01133/

-

Library of Congress Geography and Map Division; W.S. Long and Washington A. Roebling/Battle of the Antietam fought September 16 & 17, 1862/Washington, D.C./ Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3844a.cw0246000

-

Maryland Historical Trust, Cunningham Farm, WA-II-331, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, 1978, 24 March 2018

-

U.S. National Park Service, Joseph Parks Barn, Antietam National Battlefield, Historic Structures Report Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2008.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Parks Farmstead Cultural Landscape Inventory, Antietam National Battlefield, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2011.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Newcomer Barn, Antietam National Battlefield, Historic Structures Report Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2004.

-

Walker, Kevin M and K. C. Kirkman, Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape. Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

Western Maryland Regional Library, The Illustrated Atlas of Washington County, Maryland was published in 1877. Lake, Griffing & Stevenson of Philadelphia, 1877. Retrieved from http://whilbr.org/Image.aspx?photo=wcia053s.jpg&idEntry=3497&title=Sharpsburg+-+District+No.+1

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

-

U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies. Pl. XXVIII: Antietam, Suffolk, Gettysburg, Franklin. Washington, Government Printing Office, 1880-1901. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3701sm.gcw0099000/?sp=53

Leave A Comment