The most well known farmstead at Antietam is the Samuel Mumma farm. A number of accounts during the battle from both armies make reference to the farmstead and it was the only one to be deliberately destroyed during the battle. It is a vivid reminder of the destruction of war and the rebirth in its aftermath.

The property that would later become the Mumma Farmstead was comprised of at least three separate land grants to various settlers. The largest land grant was known as Anderson’s Delight. In 1761, John Reynolds, an Anglo-Irishman who migrated to Washington County from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania acquired 212 acres of Anderson’s Delight. In 1764 and 1765, Reynolds would add another 173 acres to his holdings from parts of two other tracts known as Abston’s Forrest and John’s Chance. He farmed this property until his death in 1784. According to Reynolds’ will, the 385 acres was divided between his two sons, Francis and Joseph. Joseph’s portion would later become the William Roulette farm.

As the French and Indian War was ending, Christian Orndorff, a millwright who was also from Lancaster County, arrived in the area in 1762. Now that the region was safe and open for settlement, Orndorff found a suitable site along the Antietam Creek to build a grist mill. Today we know the site as the Joshua Newcomer farm.

In 1785, Francis Reynolds’ portion (182.5 acres) was conveyed to Christopher (Stuffle) Orndorff. In 1791, Christopher (Stuffle) Orendorff sold the Reynolds property to his father Christian Orndorff. After Christian moved to his new property, he turned the the mill over to his son, Christopher.

Christian Orndorff would build the first dwelling on the property (Mumma farm) and the springhouse. In 1796, Christian passed away and the property was divided between his wife Elizabeth and another son. That same year, Jacob Mumma purchased the mill complex from Christopher Orndorff. Like many of the settlers coming to America, the Mummas were fleeing religious persecution in Germany’s Rhine River valley. They arrived in Philadelphia in 1732 and settled in Lancaster County. The Mumma family was not alone traveling down the Wagon Road to Sharpsburg, they were accompanied by Joseph Sherrick, Sr. and his family. Sherrick would also purchase property along the Antietam from the Orndorff’s.

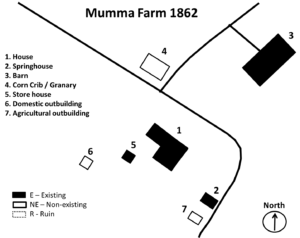

After purchasing the Orndorff Mill, which included two houses, a grist mill, a saw mill and more than 324 acres, Jacob Mumma began to buy other properties in Boonsboro and Sharpsburg . In 1805, Jacob would purchase 182.5 acres from Elizabeth Orndorff. This property, now known at the Mumma Farm, included a house, barn, springhouse and other outbuildings that had been built by the Orndorff family in the 1790’s. Over the next six years, Jacob acquired the remaining parcels of the Orndorff land.

It is believed that Jacob’s son, John was the first Mumma to live on the farm. During this time a two-story brick addition was constructed, doubling the size of the house. In 1831, Jacob sold the 182.5 acre parcel to his son, Samuel Mumma Sr. Samuel moved to the farm with his young wife and two children. Samuel had married Barbara Hertzler in 1822. Tragedy had struck the young couple shortly before moving to the farm in 1830 with the death of their third child, John. Three years later, Barbara died giving birth to their fifth child, Catherine, who died just three weeks later. Samuel was left with three sons and a large farm to take care of. Before the end of the year Samuel would marry the daughter of a neighbor, 18-year old Elizabeth Miller. Together they would have eleven children including a son who died in infancy.

As the Mumma family grew, so did the community. For years the German Baptist Brethren, or “Dunker”, congregation had met in the private home of Daniel Miller, the father of Elizabeth Miller Mumma. In 1851, Samuel donated a small 4.5 acre tract at the edge of a woodlot that would become known as the West Woods. Over the next several years a new church was constructed of bricks that were made and donated by another Dunker and close neighbor of the Mummas, John Otto.

By 1860, the Mummas owned a very diversified farm valued at $11,000. They had large yields of wheat, Indian corn, rye, Irish potatoes, clover seed, and hay. Their livestock included 8 horses, 5 milch cows, 17 other cattle, 11 sheep, and 20 swine valued at over $900. From these the Mummas were “able to obtain, 500 pounds of butter, 60 pounds of wool, and $200 worth of meat”. The orchard was producing $30 worth of apples.

September 14, 1862 started out as most Sundays, but as the members of the Dunker Church met for worship, the Battle of South Mountain erupted near the mountain gaps just six miles to the east. Later that day the Mummas invited some members of the congregation to their house for lunch. The children went up the hill above the farm to watch as the battle raged, they could see the smoke and hear the sound of guns like thunder on the mountain. The next morning as Confederate soldiers started to cross the Antietam, neighbors began meeting at the farm to see what Samuel Mumma thought they should do. He told them, “Go with me for we must get you out of the battleline.”

One of the older Mumma boys was told to take the horses away to safety as the rest of the family prepared to leave. Samuel Mumma, Jr. remembered that, “Some clothing was gotten together and the silverware packed into a basket, ready to take but in our haste to get away, all was left behind. Father and Mother and the younger children left in the two-horse carry-all (the older children walking as there was a large family) going about four miles, and camped in a large church (called the Manor Church), where many others were also congregated.” Samuel, Sr. was the last to leave as he was carrying his 3-year old daughter, Cora who was upset. Samuel had noticed his gold watch over the mantle. He grabbed the watch and hung it around Cora’s neck to settle her down. Little did he realize that beside the clothing the family was wearing, the watch would be the only item saved from their belongings.

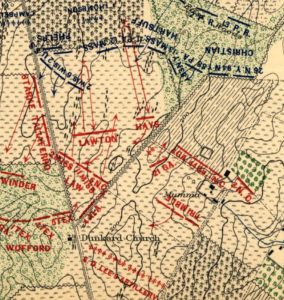

As the battle rages around the farm at around 7:30a.m., the house is set afire by Confederate forces.

Samuel Mumma, Jr. returned to the house on Tuesday evening, but found that the house had been ransacked and everything of value taken. Later, skirmishing erupted just beyond the farm across the Smoketown Road in the woods. The next morning the battle would begin in earnest. As the fighting shifted from the Miller Cornfield toward the Mumma farm, Brig. Gen. Rosewell S. Ripley’s brigade was forced back. Ripley ordered the farm burned because he feared the buildings would be taken over by advancing Federal troops and sharpshooters would occupy the buildings to pick off his officers. James Clark of the 3rd North Carolina Infantry regiment took charge of a squad of volunteers to set the Mumma farm buildings on fire. Clark “recalled throwing a torch through an open window and onto a quilt covered bed. Within a few moments the whole house was in flames.”

Throughout the day the battle swirled around the burning Mumma farm. The next evening Robert E. Lee’s Confederate forces withdrew back across the Potomac, but the “embers from the ruins of the Mumma buildings continued to smolder.” As the smoke cleared the devastation was visible, the Mumma farm was completely destroyed. “The Hagerstown Herald reported that Samuel Mumma had suffered the greatest loss as a result of the battle. In addition to his house and barn and their contents, the family lost all its furniture, clothing, grain, hay and farming implements. The fences were all destroyed, the fruit trees were striped, and the fields were trampled flat.”

When the Mumma family returned they could not believe the destruction to their farmstead. Only the brick walls and a chimney were still standing among the ruins of the house. The smokehouse was still intact and the springhouse survived, although the roof had been burned. Photographer Alexander Gardner, who worked for Matthew Brady, arrived at the Mumma farm a few days after the battle to capture the scene of not only the destruction of the buildings but of the carnage that remained on the Mumma fields near the Dunker Church.

The carnage of the battle by the Dunker Church showing dead men and animals from Stephen D. Lee’s artillery position.

Devastation at the western corner of the Mumma Farmstead, 19 September 1862. This area is now the site of the Maryland Monument Park.Monument.

Over the next several weeks the Union army encamped on Samuel Mumma’s fields. The quartermaster would requisition his “firewood, 592 bushels of corn, 75 bushels of wheat, and sixteen ton of hay which somehow escaped the fire.” Samuel attempted to get a voucher from the quartermaster, but he was told that a government commission would come around to settle his claims. The commission never came. When he did filed a claim for just the firewood and grain he was told his “losses were a direct result of the battle and therefore ineligible for reimbursement”.

Until the Mummas were able to rebuild their home, they stayed at the home of their neighbor, Joseph Sherrick, Jr. In the spring of 1863 they started to rebuild the house and the family moved back in June of 1863. As time went on the rest of the farm buildings were rebuilt and additions to the house were added.

Of course Samuel Mumma’s postwar claim for damages was extensive. The property and building included:

One house destroyed by fire($2000), one barn ($1250), one spring house and hog pen ($100), household furniture and clothing ($422.23), farming implements included McCormick reaper, a wheat drill, two grain rakes, a wheat fan and a wheat screen, six plows and a threshing machine, in addition to the usual pitch forks and other tools. He also lost 2 wagons ($457), fence destroyed ($590), land damaged by traveling and burial ($150), and fifteen cords wood ($37).

For the damages of crops, food stores and livestock, the claim included:

46 tons of hay (valued at $508), 80 bushels of wheat ($100), 20 bushels of rye ($15), 25 bushels of corn ($16.25) and 75 bundles of straw ($88). Another 75 bushels of wheat ($93.75) were plundered,

and Mumma lost 16 acres of corn ($355), 16 acres of fodder ($88), 100 bushels of Irish

potatoes ($100), 10 bushels of sweet potatoes ($15), and 15 tons of straw ($97.50). Destroyed

in the farmhouse or outbuildings were a bushel each of dried corn ($2) and dried apples ($1), a

half-bushel each of dried peas ($1.50) and beans ($.75), 1¾ bushels of dried cherries ($4), 12

crocks of preserves ($12), 12 crocks of marmalade ($12), 8 crocks of apple butter ($6), 4

barrels of vinegar ($20) and 16 gallons of wine ($24) and a half-barrel of pickles ($4). Two

household gardens, valued at $10 each, were devastated. [6] Mumma also lost a wide variety

of livestock in the aftermath of the Battle. In his claim he listed 6 steers ($150), 2 calves ($12),

2 colts ($60), a horse ($100), 9 hogs ($90), 9 shoats ($27) and 8 sheep ($40). He also lost 200

chickens ($30), a dozen turkeys ($6) and 2 ducks ($.50).

The claim was one of the only ones refused by the government, which said the Confederate forces did the damage, so the Federal government was not responsible.

In 1876, Samuel Mumma, Sr sold the farm to his son, Henry C. Mumma. Samuel died on December 7 of that year. His wife Elizabeth passed away ten years later on August 25, 1886. They are buried together in the Mumma Cemetery beside the farm, along with many of their family and friends.

In 1885, Rezin D. Fisher acquired the farm from Henry Mumma. In 1890, Congress established the Antietam National Battlefield Site which would be supervised by the War Department. As the battlefield site was being developed, “Fisher sold off small parcels of land to various states for the erection of commemorative monuments” like the Maryland Monument and New York monument parks. Fisher would sell the property to Walter H. Snyder in 1923, who owned the farmstead for just over a year. In 1924, he sold the property to Hugh and Hattie Spielman who would farm the property until 1961. “With the passage of the Congressional authorization for additional land acquisition for the battlefield in 1960, the Park Service quickly moved to purchase the Mumma property. The 148.5 acre tract was acquired from Hugh and Hattie Spielman in December 1961 at a cost of $51,570”. The Spielman’s would remain on the property with an agricultural lease until the mid-1980s.

As part of the “Mission 66” program the National Park Service built a new visitor center in 1962 on the newly acquired Mumma farm near the New York Monument Park. After the Spielman’s moved off the property, the Park Service performed a stabilization and preservation project of the house in the 1990s. In late 2001 the preservation work on the exterior of the farmhouse began and the interior was restored. Today the Mumma Farm is used by the National Park Service for ranger-led educational programs for school groups and other youth groups coming to the battlefield. The Samuel Mumma farmstead was an eyewitness to history and a tragic reminder of the impact of the battle on the local population.

-

Ernst, Kathleen A., Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign, Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999.

-

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/related/?fi=subject&q=Antietam%2C%20Battle%20of%2C%20Md.%2C%201862.&co=cwp

-

Reardon, Carol and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Antietam: experiencing the battlefield through history, places and people, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

-

Schildt, John W., Drums Along the Antietam. ParsonMcClain Printing Company, 2004.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Historic Preservation Training Center, Historic Structures Report for the Samuel Mumma House, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1999.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Mumma Farmstead Cultural Landscape Inventory, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2004.

-

Walker, Kevin M and K. C. Kirkman, Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

Elizabeth Motter Fletcher,my maternal great Grandmother, was given the Star Barn by her father, John Motter. We are coming to the area Mon July 17 to see the Star Barn in its new location & would also like to see the Samuel Mumma Farm if possible.

Very best —

Martha Alexander