Today the Henry Piper farm sits back off of the Old Hagerstown Pike. It is one of the oldest farmsteads in Washington County and the only historic farmhouse on the Antietam National Battlefield that is currently occupied by a tenant. On the morning of September 17, 1862, the Piper Farmstead sat in the center of Robert E. Lee’s battle line and would be engulfed by the fighting along a sunken country road that would be forever known as the “Bloody Lane”.

In 1790, Joseph Chapline, Jr. had the lands that he received from his father surveyed and patented into a new single tract. This 2,575 acres became known as Mount Pleasant. On the eastern side of this tract, between the old Hagerstown Road and north of the Boonsboro Pike, the surveyor noted that there had been improvements on the property “as being 5,200 old rails, two old cabins, and seventeen apple orchard trees”. The property known as “Elswick’s Dwelling” had been cultivated and grazed on and it is possible that it was first used as a farm in 1740. Although the location of the ‘two old cabins’ remains a mystery it is believed that a section of the building next to the current house, later used as a summer kitchen and servants quarters, is the first dwelling on the Piper Farm.

John Miller, a Pennsylvanian German from Franklin County migrated to Washington County with his parents around 1791. His father, John Johannas Hannas Miller, was a member of the Church of the Brethren, also known as Dunkers. John Miller was a farmer and he started buying land along the Hagerstown Road, including several tracts that would become the Samuel Poffenberger farm, the William Roulette farm and the Henry Piper farm. According to the 1803 tax assessment for the “Sharpsburg Hundred”, John Miller owned 632 acres on two patents located north of Sharpsburg. When John Miller died in 1821 without a will, his estate was divided among several of his children. His one son, Jacob Miller received a portion of “Elswick’s Dwelling”

Whether Jacob Miller lived here at the time or not is unknown. Jacob was very wealthy and “very successful in his enterprises. He managed several farms, a grist mill, a saw mill and a flour mill”. Jacob had built a house in Sharpsburg and it is likely that he rented the farm out to tenants. It was also around this time that the icehouse, or cave house, was built into the side of a small bank from fieldstone. The two-room structure was used to store produce in one side and ice storage in the other. The southern end of the large stone and frame bank barn was built around 1820 as well. A wooden addition would be added to the northern end of the barn in 1914, doubling its size to 144 by 44 feet.

In 1843, Henry Piper and his family moved to the farm as tenants of Miller. Henry was the son of Daniel Piper, a well known resident of Sharpsburg. Daniel Piper was the son of (John) Jacob Pfeiffer (later Piper) who emigrated from Germany to the Sharpsburg area in 1763. Daniel raised his family on a farm west of Sharpsburg, including a daughter, Martha Ann who married Henry Rohrbach in 1835 and lived on the Rohrbach family farm just east of the Lower, or Burnside, Bridge. Daniel Piper purchased the property from Jacob Miller in 1846 for his son.

Henry Piper married Elizabeth (Betsy) Keedy on November 18, 1828 and together they would have six children. By 1854, Henry and Betsy had purchased the farm from his father. Henry was known “as a rather austere man with a penchant for fashionable hats. He was rarely seen in town without his tall brimmed hat” and was nicknamed ‘Old Stovepipe’.

The Piper family lived on a prosperous 231-acre farm stretching between the Hagerstown Pike to the west; the Hog Trough Road to the north and east; to the Boonsboro Pike and the edge of Sharpsburg to the south.

The Piper family were “typical of the region in being both avowed Unionists and slaveholders”. In 1860, Henry owned six slaves, five of them children, one of the slaves on the farm in 1862 was Jeremiah (Jerry) Cornelius Summers. He was born on the farm in 1849. A 16 year-old free black farm hand named John Jumper also worked on the farm. The slave quarters, thought to be the first dwelling on the farm, served as the kitchen as well.

Piper apple trees

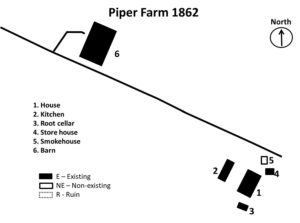

It is unsure who built the main house, but by 1860 the 40 x 15 feet two-story frame farm house consisted of five or six rooms with a smokehouse and several other outbuildings around. Just north of the house was a 17-acre apple orchard and by the barn, Henry had an apple press to produce cider. The Piper orchard “was one of the largest in Sharpsburg and the only commercial orchard in the area at the time of the battle”.

Just beyond the orchard the Pipers, like their neighbors, had a twenty-five acre cornfield that still needed to be harvested in September 1862 and most of Henry’s other fields “were freshly plowed, ready for planting winter wheat”. That year the family had grown bushels of Irish potatoes, sweet potatoes, onions and cucumbers. The farm had a variety of livestock, such as horses, milk cows, cattle, sheep, swine, chickens, geese, and turkeys.

On September 15, 1862 the Piper family farmstead was inundated by Confederate soldiers as they prepared their positions on the ridgeline northeast of Sharpsburg and along the Hog Tough Road. During the afternoon, Confederate Generals James Longstreet and D.H. Hill had arrived and chose to use the Piper house as their headquarters. That evening, the Piper daughters served dinner to the generals and offered them wine. Gen. Longstreet initially refused, by seeing that it had no ill-effect on Daniel Harvey Hill, Longstreet accepted the offer saying, “Ladies, I will thank you for some of that wine”. After dinner, the Pipers heeded the general’s advice to leave the farm.

Mr. Piper and his daughters “quickly packed what they could carry into a wagon, and Elizabeth buried her dishes in the ash pile“. Mary Ellen Piper remembered as they were leaving, “We left everything as it was on the farm, taking only the horses with us and one carriage“. The Pipers traveled to Henry’s brother’s farm and mill. Samuel Piper’s mill was just northwest of town along the Potomac where the family could seek shelter from the impending battle.

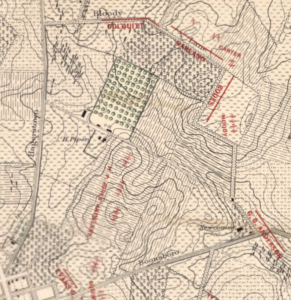

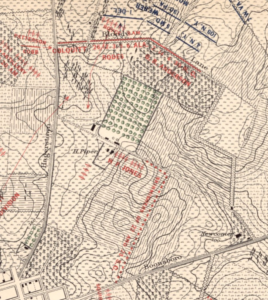

At the center of Robert E. Lee’s battle line just north of Sharpsburg was the farmstead of Henry Piper. Along the Hog Trough Road at the edge of his farm, Confederate infantry were posted. To the south of the house on the ridge leading to the Boonsboro Pike, four artillery batteries were positioned in Henry’s freshly plowed fields. As the battle began at daybreak, these Confederate units began moving across the Piper farmstead to confront the advancing Union forces from the north. By 9:00 a.m. the battle had shifted from the Miller and Mumma farm and the Piper farm was soon engulfed by the fighting at the Sunken Road.

For two days the Pipers waited, listening to the sounds of the fighting and the distant rumbling of army wagons traveling to Shepherdstown. On September 19, the Pipers departed for home. Mary Ellen Piper recalled, “On our return the Union forces were encamped upon the farm and in the vicinity, and the Union cavalry were moving along the Hagerstown pike in great numbers towards Sharpsburg“. As they neared the farm, death and destruction was all around them. Their barn had been shelled, but unlike their neighbors the Mumma’s and the Reel’s barns that had burned, the Piper’s was saved from destruction possibly due to the green hay stored inside. “Wounded soldiers were lying on the floor of every room. One had the family bible propped up in front of him, tearing out each page as he finished reading“.

Mary Ellen recounts that, “We brought back the horses with us, and they were put in the barn. A large number of cattle, sheep and hogs belonging to father still remained on the place. I saw the Union soldiers butchering some of the cattle, when we came back…. The Union forces were encamped in the vicinity for several weeks after the battle – at least some portion of them. During this time… all the cattle and sheep on the farm were taken and used by U.S. military forces. The sheep were all taken the day after we returned home. The hogs and cattle were slaughtered at different times. I remember four of the calves were slaughtered in the orchard back of the blacksmith shop”.

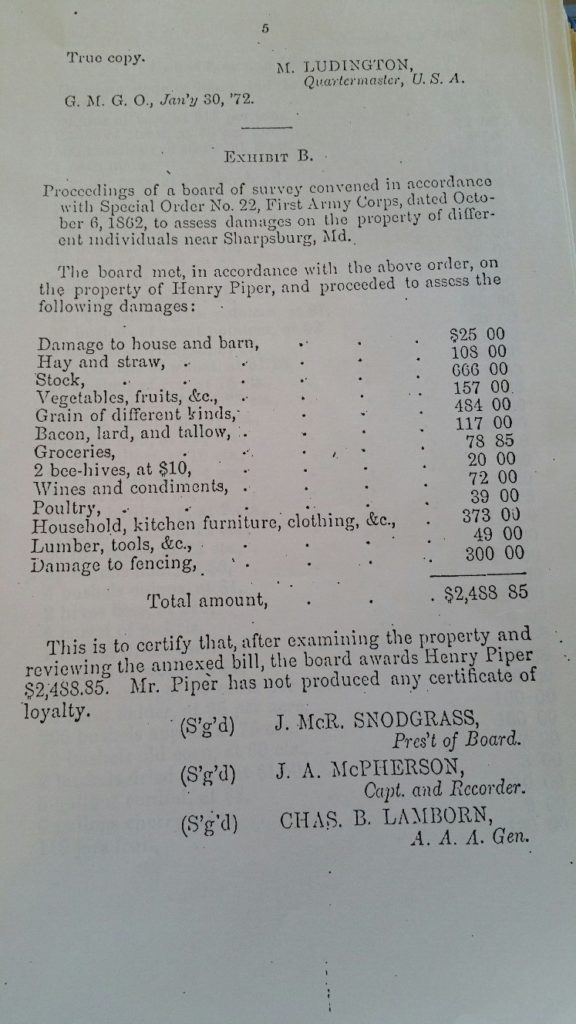

Initially Henry Piper only filed a claim for $25 for the damage to the house and barn but soldiers had not only slaughtered and taken a lot of the livestock but had “ate two hundred of Piper’s chickens, fifteen geese, along with twenty-four turkeys”. They also took “one hundred bushels of Irish potatoes, thirty bushels of sweet potatoes,… six barrels of vinegar, eight hundred pounds of bacon, five sacks of salt, four bushels of onions, pickles, one bushel of dried cherries, two hundred bushels of apples, six gallons of cherry wine, and one hundred and ten jars of fruit. They took thirty dollars worth of men’s clothing, and sixty dollars worth of lady’s clothing”. Henry would later amend his initial claim and the board of survey would assess the damage to the Piper farm as follows:

- Damage to house and barn $25.00

- Hay and straw 108.00

- Stock 666.00

- Vegetables and fruits, etc. 157.00

- Grain of different kinds 484.00

- Bacon, lard and tallow 117.00

- Groceries 78.85

- 2 bee-hives at $10 20.00

- Wines and condiments 72.00

- Poultry 39.00

- Household, kitchen furniture, clothing, etc. 373.00

- Lumber, tools 49.00

- Damage to fencing 300.00

Total: $2,488.85

Although the board awarded Henry Piper this amount, no payment followed because he did not produce any certificate of loyalty. Twenty-four years later in November 1886, Henry Piper sued the U.S. Government for the damages to his farm and Mary Ellen Piper Smith’s descriptions of the damages were part of her testimony given in support her father’s claim.

In 1863, Henry and Betsy moved into Sharpsburg to the house that Henry acquired in 1857 following his father death. The house sits on the corner of Main and Church Streets across from the Holy Trinity Lutheran Church. Elizabeth Piper died on January 19, 1887. Almost five years to the day of her death, Henry would pass away They are buried at the Mountain View Cemetery in Sharpsburg.

Henry’s son, Samuel, took over the farming operation and would continue farming until 1898 when he moved to Hagerstown. During this period a wing was added to the house and additions and improvements were made to the servants quarters. In the 1890’s, the War Department began purchasing property in order to build a road through the battlefield. In an attempt to preserve the historic part of Bloody Lane as best they could, a road was built to the south of it, in what would have be been Henry Piper’s cornfield at the time of the battle. In 1896, the War Department constructed the Observation Tower at the end of Bloody Lane. In 1966, Richardson Avenue, as it was named, was moved farther away from the lane and expanded to include parking areas at both the center of the lane and at the Observation Tower.

The farm would remain in the Piper family until 1960 but rented out over those years. Samuel’s son, Elmer E. Piper owned the property from 1912 until 1933, and then his son, Samuel Webster Piper held it until 1960. Webster sold the land to the Antietam-Sharpsburg Museum, Inc. According to local historian, John Schildt, a log cabin building was constructed across from the National Cemetery which housed historical and educational displays. Unfortunately, shortly after the 100th year anniversary of the battle the company was forced to closed due to financial difficulty and the construction of the new Park Visitors Center.

In 1964 the farm was sold to the National Park Service for $75,000. Over the next twenty years the buildings would be restored and at one time the Park Service operated “the farm as a ‘living farm’ growing crops, raising livestock and using farm implements and conservation practice similar to those employed in the early 1860’s”.

In 1985, Doug Reed signed a 56-year lease with the National Park Service with intention of restoring the farmhouse and using it as a Bed and Breakfast. In 1994, Regina and Louis Clark took over as the Innkeepers of the Piper House Bed and Breakfast and continued to operate it for ten years. Today they still live at the farmhouse and entertain ancestors of the Piper Family from time to time. The “surrounding fields remain an active farming operation” that is leased out by the National Park Service to local farmers. They cultivate the crops, care for the livestock, and maintain the orchard; keeping the agricultural landscape thriving on one of our oldest farmsteads in the area, and an eyewitness to the fighting at the Bloody Lane.

A special thanks to Regina & Lou Clark for taking the time to show me around the Piper Farm and sharing a wealth of information about the Piper family and the farmstead.

Sources:

-

Ancestry.com, Henry Piper Family, Census Data 1850-1900. Retrieved from: https://www.ancestry.com\

-

Clark, Lou and Regina Clark, Personal Collection of the Piper Family History. Sharpsburg, reviewed July 2017.

-

Ernst, Kathleen A., Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign, Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999.

-

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, Piper Farm, House, Sharpsburg, Washington County, MD. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.md1099.photos/?sp=1

-

Maryland Historical Trust, Piper Farm, WA-II-335, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, 2009.

https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/Washington/WA-II-279.pdf. -

Reardon, Carol and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Antietam: experiencing the battlefield through history, places and people, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

-

Schildt, John W., Drums Along the Antietam. ParsonMcClain Printing Company, 2004.

-

The Piper House, photos of Henry & Elizabeth Piper. Retrived from http://www.pathsofthecivilwar.com/piperhouse/history.htm.

-

The Morning Herald, Piper Farm: Employing methods of the 1860’s. Hagerstown, MD, July 13, 1976. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/23053138/.

-

Trail, Susan W., Remembering Antietam: Commemoration and Preservation of a Civil War Battlefield, Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Maryland, 2005.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Antietam National Battlefield, National Register of Historic Place, ANTI-WA-II-477, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1990.

-

Walker, Kevin M and K. C. Kirkman, Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape. Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

My mother was a Piper, daughter of Alva A. Piper. I visited the farm in 1961 with my family and Webster Piper’s son took us around. My Mom and dad stayed in the Piper home when the Piper’s were there in the fall, can’t remember the year. Maylon Piper took card of the arrangements and were treated royaly.

That is very interesting, thank you for sharing your family story.