As you drive through the Antietam National Battlefield you will see the monuments across the low rolling hills, in woodlots, along cornfields and old farm roads. They are dedicated to the men who fought here over 150 years ago. You may wonder, how are we connected to the past through these monuments in our backyard? Here is the story of one connection.

September 17 marks the anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest one-day battle in American history. An estimated 23,000 soldiers were killed, wounded or missing after twelve hours of some of the most savage fighting of the Civil War. The Battle of Antietam ended General Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the North and led to the issuance of President Abraham Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

For many Union soldiers, Antietam would be their first sting of battle or ‘baptism of fire’. For one young man named Henry Vincent it would be his first such action. Henry was born on Christmas Day, 1844, in England. In 1852, his father Job immigrated with his family to America where they settled in Montour County near Danville, Pennsylvania. Henry worked in the local roller mills from the age of ten until he answered President Lincoln’s call for 300,000 more volunteers in July 1862.

Henry enlisted in the Danville Fencibles, which was comprised of men mostly from the Danville Iron Works. By mid August, they joined other recruited companies from Wyoming, Bradford, Carbon, Luzerne and Columbia counties at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg where they were mustered into service as a ‘nine-month regiment’ and organized as Company A, 132nd Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers. Richard A. Oakford of Luzerne County was appointed colonel of the regiment and within days the regiment was moved to the front on the outskirts of Washington. For the next two weeks the regiment encamped near Fort Corcoran, just across the Potomac, where they drilled intensely amidst the sound of the guns from the plains of Manassas.

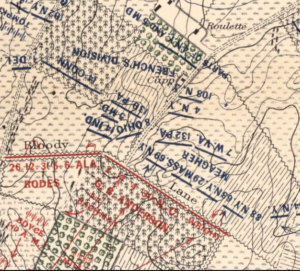

On September 7, 1862, Henry and the men of the 132nd marched twenty-two miles in seven hours to Rockville, Maryland, which was an amazing feat for any regiment, especially a green one. Here the 132nd was assigned to Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball’s First Brigade alongside of three veteran regiments, the 8th Ohio, 7th West Virginia and the 14th Indiana. The First Brigade was part of the Maj. Gen. William H. French’s Third Division of Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner’s Second Corps in the reorganized Army of the Potomac under the command of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan.

Once they joined the ranks of the Army of the Potomac there was no rest for the regiment. Just days before, Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia had crossed the Potomac to invade Maryland and now McClellan was moving to intercept Lee. By September 13, Henry’s regiment had marched to an open field near Frederick, MD to bivouac for the night. The same field had been occupied by Confederate soldiers a few nights before as the rebel army was on the move to South Mountain and McClellan was on their tail. The next day the regiment was on the march again. By the time they reached Fox’s Gap on the evening of the 14th, the battle for South Mountain was over, with the exception of some artillery batteries firing back and forth at each other. It was here that Henry and his fellow comrades would witness the sight of their first dead soldiers, an image that would stay with them the rest of their lives.

On the morning of September 15, the Army of the Potomac began their “chase” of the rebel army through the gaps of South Mountain as they marched toward the small village of Sharpsburg. The next day the regiment made its way to Keedysville, along the Antietam Creek, where it bivouacked for the night in preparation for the next day’s battle. That evening the camp was still–no singing or fires, except to make some coffee. As one man from the regiment wrote, ‘Letters were written home–many of them last words–and quiet talks were had, and promises made between comrades.’ Colonel Oakford had asked his adjutant to ensure the regimental rosters were complete for ‘We shall not all be here to-morrow night.’ That night a light rain fell as they lay on the ground under their gum blankets.

The next morning on September 17, the men quickly awoke to the simple call from their sergeant or corporal. They were on the march about 6:00am, wading across the waist deep Antietam Creek. Soon the cannonading and the shrieking of shells could be heard. One veteran wrote they knew they were approaching the ‘debatable ground’ when they heard the rattle of musketry which sounded ‘like the rapid pouring of shot upon a tinpan, or the tearing of heavy canvas, with slight pauses interspersed with single shots.’ The Second Corps had been ordered into battle in an effort to turn the Confederate left flank and assist the Twelfth Corps near the West Woods. Maj. Gen. Sumner had escorted his lead division, under Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, on the attack as French’s division was directed to support on the left flank. When Sedgwick’s division came into contact in the West Woods, Gen. Summer had sent French orders to press the attack toward the Sunken Road. French had moved to the south of Sedgwick’s attack and ran into Confederate skirmishers near the swales around William Roulette’s farm. Seeing an opportunity for a fight he ordered his men forward.

As the men of the 132nd were ordered into line of battle behind the other two brigades of French’s division, they were marching past the Roulette farm when a shot from a Confederate battery slammed into the Roulette’s yard. The men quickly moved through the yard trampling over the family garden and smashing into some white crates in the yard which were the Roulette’s bee hives. The annoyed bees engulfed the regiment. Some men dropped their muskets and ran into nearby fields, while others slapped their clothes and batted at the angry honey bees. In the meantime, more Confederate artillery shells and bullets were finding their marks among the Union troops. One soldier wrote, “Soldiers were rolling in the grass, running, jumping, and ducking.” Concerned that the hysteria that gripped the 132nd could rapidly spread to wholesale panic among the rest of the brigade, Brig. Gen. Kimball barked out a “double quick” order allowing the Pennsylvanians to advance past the Roulette farm and eventually outdistance the bees.

Kimball’s staff and regimental officers hurried to rally the regiment back into battle lines with the rest of the brigade. The regiment advanced across open fields toward the Sunken Road just to the east, the lane that led to the Roulette farm. They were slightly to the rear between the two smaller veteran regiments of the 8th Ohio and the 7th West Virginia. As they crested the hill the Confederates opened with a terrific volley of musketry that brought down many of the Union line. Colonel Oakford died in the first volley from a minie ball that struck an artery in his left shoulder. Henry’s own First Sergeant, 1st Sgt J. M. Hassenplug was killed. With no cover from the fire, the 132nd was ordered to lie down and crawl toward the Rebel lines below the crest of the ridge where they reloaded and fired individually. One soldier that was next to the adjutant, “inadvertently stood up, a minie ball struck his rifle in the forestock and prostrated him. Regaining his senses, the fellow discovered he was only bruised. He picked up another gun and returned to the line.”

The regiment held their ground as the men of Maj. Gen. Israel B. Richardson’s division came up to support their attack. The famed Irish Brigade continued the assault past the 132nd toward the Rebels. To their left flank another Union brigade was able to hit the flank of the Confederate line seizing a knoll overlooking the Sunken Road forcing the Rebels to withdraw.

Seeing them run, the men of the 132nd rose up and pursued the Rebels into the lane. Richardson’s brigades pursued the retreating Confederates toward Sharpsburg until Confederate Generals James Longstreet and D.H Hill personally led a counterattack with artillery and 200 men. Richardson was forced to withdraw back to the lane.

The fighting around the Sunken Road had ended around one o’clock. The men of the 132nd continued to hold the line the rest of the day and into the next. According to the official report after the battle, they had taken over 750 men into battle; thirty men were killed, one-hundred and fourteen wounded and eight were missing from the ranks. At least thirty of the wounded would die from their wounds within days after the battle. More than 5,600 casualties were inflicted on both sides around the Sunken Road. The carnage was so horrifying that the Sunken Road would be forever known as the ‘Bloody Lane’.

As for Henry Vincent, he made it through his ‘baptism of fire’ unscathed. According to the county history, “his coat sleeve was completely shot off at Antietam.” Henry would continue to serve with the 132nd and participate at the battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. He was promoted to Corporal in March 1863 and was mustered out with Company A on May 24, 1863. Henry returned home to Danville, to become a successful businessman, lawyer and a father to eight children. He was an active member in both the 132nd Pennsylvania Volunteer Regimental Association and the Goodrich Post No. 22, of the Grand Army of the Republic until he passed away in 1916.

For many of us, the monuments in our backyard connect us to the past. The 132nd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment monument at the Sunken Road and Henry Vincent, will forever be my connection to the Battle of Antietam, as Henry was my great-great-grandfather.

Leave A Comment