“We were awakened before daylight by the cook, who had brought up a pail of steaming coffee, some johnny-cakes and “fixins,” together with cups, plates and other table ware. A blanket was spread on the ground for a table-cloth, on which was placed the breakfast, and the officers gathered around it on their haunches. It was the early gray light that appeared just before the sun rises above the horizon, and we could little more than distinguish each other. We had not half finished our meal, but it had grown considerably lighter, and we could see the first rays of the sun lighting up the distant hilltops, when there was a sudden flash, and the air around us appeared to be alive with shot and shell from the enemy’s artillery – The opposite hill seemed suddenly to have become an active volcano, belching forth flame, smoke and scoriae.

Captain J. Albert Monroe of Battery D, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery was positioned on the hill just north of the Joseph Poffenberger barn among the United States Army First Corps. Monroe described the first shots of the Battle of Antietam in the early morning hours of September 17th as Confederate artillery fire rained down on them from the distant hilltops of the Jacob Nicodemus Farm. Many visitors to the battlefield know about Nicodemus Heights, and every Antietam aficionado dream of getting up to the heights to see what the Confederate artillerymen saw, but very few know about the Jacob Nicodemus family and their experiences.

Johann Conrad Nicodemus was born in Bavaria, Germany and immigrated to America in the mid-1700’s. After landing in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, his family soon moved to Lancaster. Johann would eventually marry, have eight children and fight in the American Revolution. Two of his sons, Valentine and Conrad moved to Washington County, Maryland, settling near Boonsboro. Valentine purchased 175 acres and built a house along Dog Creek where the Nicodemus Mill would be built in 1829. Conrad married Sophia Thomas, the daughter of Rev. Jacob Thomas of the United Brethren Church. Rev. Thomas owned a large tract of land around Boonsboro and divided it into several farms, one would be given to his new son-in-law. Conrad and Sophia would have 13 children over the next twenty-two years. The second to last child, was Jacob, born on May 3, 1819.

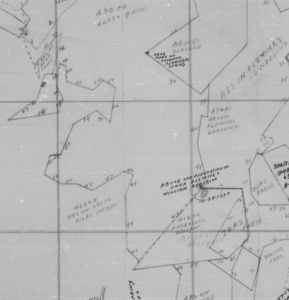

The area around what we know today as the Nicodemus Farm was once part of two land tracts. These two patents were originally part of James Chapline’s “Addition to Loss and Gain” and part of Col. Edwin Sprigg’s “Resurvey on Addition to Piles Delight”. Some of the land that Jacob Mumma, the patriarch of the Mumma family, had been acquiring in the area included a large parcel of “Addition to Loss and Gain”. Around this same time, John McPherson and John Brien, both well-known land speculators and owners of the nearby Antietam Iron Works, were selling off parcels of the “Resurvey on Addition to Piles Delight” tract. Michael Havenar purchased a parcel just north of what we know today as the Alfred Poffenberger farm.

In 1820, Jacob Coffman (Kauffman), future father-in-law to Joseph Poffenberger, purchased 100 acres from Jacob Mumma. Coffman’s farm was adjacent to this tract and he continued to add to his holdings acquiring the acreage that had belonged to Michael Havenar. By 1850, Jacob Coffman owned over 500 acres valued at $35,000. One of the farms that he acquired would become the home of Joseph and Mary Ann Poffenberger which he sold to his son-in-law in 1852.

During this time Jacob Nicodemus married Amelia Drenner in 1844 and they were living in the Bakersville area according to the 1850 census. It appears that Amelia may have died during child birth. Within a few months Jacob would marry Hannah Miller, the eighteen year old daughter of Jacob Henry Miller from the Keedysville area. Hannah and Jacob may have been living with family or near the Hitt (Upper) Bridge in the 1850’s while they began raising a family. According to the 1860 Census some of their neighbors included: Samuel Pry, Jacob Cost, Sarah Snyder, and Susan Hoffman; all residents along the Williamsport-Keedysville Road, In 1852, they had their first child, Samuel. Two year later they had a daughter named Sophia, but Sophia died just before reaching her fourth birthday. They had two more sons, Jacob C. and Otho.

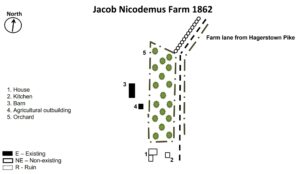

At some point after 1860, Jacob and Hannah moved with their three sons to the tenant farm owned by Jacob Coffman. With them was a twenty-one year old farm labor, Alexander Davis and his mother, Elizabeth. They also owned a thirteen year old slave girl. Most likely the Coffman’s built the farm and one of Jacob Coffman’s children lived on the tract before the Nicodemus’ moved there. Alexander Davis described the the farm as they “had a log house with two rooms downstairs and just a sort of loft divided by a partition up above. There was what we called a bat-house with a couple of bedrooms in it attached to the rear like a shed. In winter we used a room in the house for a kitchen, but in summer the kitchen was in another building off a little piece from the house. We had one of these old German barns with a roof that had a long slant on one side and a short slant on the other. The roof was thatched with rye straw”.

In addition to these buildings, there was a wagon shed, corn crib, a blacksmith shop and several other dependencies with a small orchard stretching along the farm lane. The property stretched to the west over the a ridge line toward the Potomac River, where there was a 16-acre cornfield and a small woodlot in the northwest corner of the tract. South of the farm buildings there was a 25-arce field used for the grain crops like oat, wheat and rye. These were typically harvested in the late summer and the fields reploughed for a winter crop. Hay was stacked near the barn, and wheat shocks dotted the fields. Rail fencing bordered the different fields across the farm with a few stone fences along the lane leading to and from the the farmstead. As for livestock, Alexander Davis said they “had ’bout a dozen large hogs and mebbe eighteen or twenty pigs… quite a few cattle. I suppose there was over twenty head . . . We had four geese and ’bout sixty chickens,.. There was six horses”

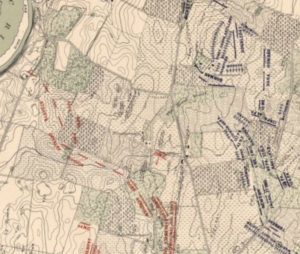

On September 15, 1862, the Nicodemus family was caught in a brewing storm as the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia began to converge on their community and the Union Army of the Potomac pursued them to the Antietam Creek. Initially on the 16th, the rebel line was anchored south of the Nicodemus farm at the edge of the woodlot between Jacob’s farm and that of Alfred Poffenberger with just the small 9th Virginia Cavalry, but later Major General J.E.B. Stuart reinforced the left flank with the rest of the cavalry regiments from Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee’s brigade. They line stretched east across David R. Miller’s fields and the Hagerstown Turnpike into the woodlot between Sam Poffenberger and Samuel Mumma’s farm. Later in the afternoon a cannonade began as Union soldiers from the First Army Corps that crossed the Antietam Creek advanced to the Joseph Poffenberger farm and into the East Woods where heavy skirmishing continued into the night. Sensing that the fight would be renewed the next day on the left, Major General Thomas J. Jackson moved artillery batteries in the early morning hours onto Nicodemus Heights. About fifteen cannons would be in position at first light under the command of Capt. John Pelham.

At daybreak, the battle began just as Capt. Monroe described it, but soon his guns were returning fire onto Pelham’s guns on the heights and among the Nicodemus farm. The family must have assumed they were safe where they were for Captain William Blackford, a staff engineer for Jeb Stuart recalled,

“Between our cavalry lines and the enemy stood a handsome country house in which, it seems, all the women and children in the neighborhood assembled for mutual protection… Between us and the house was a roughly ploughed field. When the cannonade began [at dawn on September 17], the house happened to be right in the line between Pelham’s battery and that of the enemy occupying the opposite hills, the batteries firing clear over the top of the house at each other. When the crossing shells began screaming over the house, its occupants thought their time had come, and like a flock of birds they came streaming out… children of all ages stretched out behind, and tumbling at every step over the clods of the ploughed field. Every time one would fall, the rest thought it was the result of a cannon shot and ran the faster. … I galloped out to meet them and represented to them that they were safer probably where they had as many children as my horse could carry, I escorted them to our lines and quieted the fears of the party, assuring them that they were not in danger of immediate death”.

Soon, Union forces were advancing south across D.R. Miller’s farm where they meet heavy resistance. The Union extended their line across Hagerstown Pike on to the Nicodemus farm to guard the right flank and work the Confederate guns off the heights. Confederate counterattacks across Miller’s fields were met with more Union brigades coming into the fight. By 9:00am Federal forces had driven the Rebels beyond the Dunker Church and were now advancing west across the Hagerstown Pike to roll the Confederate flank. Just as they reached the far side of the West Woods, fresh Confederate troops from Maj. Gen. Layette McLaws’ division and others rolled through the West Wests into the flanks John Sedgwick’s Union brigades forcing them to retreat north across the Nicodemus and Miller farms.

Regiments from the lead Union brigade were directed to form a line along the stone fence on the Nicodemus farm as other regiments fell back. Colonel Alfred Sully, of the 1st Minnesota wrote,

“Our loss here was very heavy, yet the men bravely held their position, and did not leave it until after the two brigades in rear had fallen back and the left regiments were moving, when they received the order to retire. Retiring in line of battle, we again halted outside the woods, to hold the enemy in check while the rest were retiring. Here the Eighty-second New York with their Colonel and colors reported to me, and formed on my right. The Nineteenth Massachusetts also reported, and formed on my left. We were soon again engaged with the enemy, but, seeing that the enemy were turning my right, I ordered the line to fall back in line of battle. The regiment here also suffered greatly in killed and wounded. We again made a stand near some farmhouse for a short time, and there took up a strong position about 100 yards back, behind a stone fence, when a section of artillery was sent to assist us. We kept the enemy in check till they brought a battery of artillery on our flank, which compelled me to order the regiments back to join our line of battle”.

Colonel Henry Hudson, commanding the 82nd New York Infantry joined the 1st Minnesota in their stand across the Nicodemus farm. Hudson stated,

“We then fell back to the outer edge of the wood, and formed on the First Minnesota to hold the enemy in check, till ordered by Colonel Sully, to whom I had reported, to fall still farther back, which we did in good order. We again made a stand behind a stone wall, and poured in our fire upon the enemy till they brought a battery of artillery on our flank, when we were obliged to fall back and join the other regiments of the brigade in good order on the edge of the wood, not more than 500 yards from the spot where our right rested.”

As the Confederate infantry pushed the Union troops out of the West Woods across the Nicodemus farm and toward the Miller barn they were supported by artillery. Rebel batteries reoccupied the heights overlooking the farmstead, and guns were positioned in the ploughed field near the house and on the ridge by the Houser farm.

In their hasty withdraw across the Nicodemus farm a number of Union soldiers were killed or wounded. Many of the wounded were seeking refuge in and around the buildings. Captain Norwood Penrose Hallowell, a company commander in the 20th Massachusetts Infantry recalled,

“Before long I gained the little farmhouse marked on the maps as the Nicodemus House. The yard was full of wounded men, and the floor of the parlor, where I lay down, was well covered with them. Among others, Captain O. W. Holmes, Jr., walked in, the back of his neck clipped by a bullet.

The first Confederate to make his appearance put his head through the window and said : ” Yankees?” “Yes.” “Wounded?” “Yes.” “Would you like some water?” A wounded man always wants some water. He off with his canteen, threw it into the room, and then resumed his place in the skirmish line and his work of shooting retreating Yankees. In about fifteen minutes that good- hearted fellow came back to the window all out of breath, saying: ” Hurry up there! Hand me my canteen! I am on the double-quick myself now! ” Some one twirled the canteen to him, and away he went”.

Hallowell and Holmes, along with many of the Union wounded would make it back to the Union hospitals that were quickly overwhelmed with the wounded from across the battlefield.

By the afternoon, the heavy fighting had shifted from left of the Confederate line to the right, southeast of Sharpsburg. The left line was reestablished across the Nicodemus farm by Stuart’s cavalry supported by artillery batteries on the high ground. Soon, nightfall ended the bloodiest single day of the war. That evening both sides began gathering their wounded and burying the dead. This continued into the next day as there was no fighting. Later that day and into the evening the Confederates withdrew from the field back across the Potomac River.

Alexander Davis came back to the farm on Thursday before the family had returned. Davis recalled the number of wounded and the fact they had no food in the house. He said,

“The house was full of wounded Northern soldiers, and the hogpen loft was full, and the barn floor. The wounded was crowded into all our buildings. I looked around to find something to eat, but there wa’n’t enough food in the house to feed a pair of quail. We’d left fifty pounds of butter in the cellar and seventy-five pounds of lard and twenty gallons of wine — fine grape wine — and half a barrel of whiskey. We had just baked eight or ten loaves of bread the day before, and pies, and I don’t know what else. Those things was all gone. So was every piece of bacon from the smoke-house.”

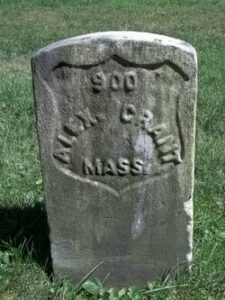

By the end of the week the dead had been buried. There were over twenty-five soldiers across the farm. Fifteen of them were from Massachusetts. One of the soldiers that he buried may have been Private Alexander Grant, Company I, 19th Mass. Infantry. Grant was a 19-year old butcher from Boston. He now rests in the Antietam National Cemetery. Davis remembered that “The stench was sickening. We couldn’t eat a good meal, and we had to shut the house up just as tight as we could of a night to keep out that odor.” Although Davis did not indicate how many Confederates were buried on the farm, according to the Bowie List there were at least six, all unknown.

In the proceeding days after a battle, soldiers can recollect the sights, sounds, and smells of the battlefield years later, just like it was yesterday. Civilians that experience such a catastrophic event are the same way. Alexander Davis remembered what all the Sharpsburg civilians experienced in those days, weeks and months after the battle.

“The battle made quite a change in the look of the country. The fences and other familiar landmarks was gone, and you couldn’t hardly tell one man’s farm from another, only by the buildings, and some of them was burnt. You might be out late in the day and the dark would ketch you, and things was so torn and tattered that you didn’t know nothin’. It was a strange country to you. I got lost three or four times when I thought I could go straight home.

Another queer thing was the silence after the battle. You couldn’t hear a dog bark nowhere, you couldn’t hear no birds whistle or no crows caw. There wa’n’t no birds around till the next spring. We didn’t even see a buzzard with all the stench. The rabbits had run off, but there was a few around that winter — not many. The farmers didn’t have no chickens to crow. Ourn [Ours] didn’t commence for six months. When night come I was so lonesome that I see I didn’t know what lonesome was before. It was a curious silent world.”

The farm was devastated. Most of the fence rails were taken for firewood and some of the others were used to burn the dead horses. The wheat and hay stacks were full of shell fragments and lead. A good portion of the corn had been trampled down and most of the potatoes were dug out of the ground by the soldiers. When the shelling started, the cattle and hogs jumped out of their pasture and headed for the woods down by the river.

Seven months after the battle, Hannah and Jacob were overjoyed at the birth of a daughter, Budelia in March of 1863. Despite the damages to their farm, the Nicodemus family stayed on to raise their family. A few weeks later Jacob purchased the farm for $5,992.50 from the heirs of Jacob Coffman who had died in 1859. It seemed that they were on the road to recovery in 1863, but before the end of the year tragedy stuck the Nicodemus family three-fold. In late November, seven-year old Jacob died. Less then two weeks later, little Budelia died followed by her brother, Otha just short of his fourth birthday. No information is available as to what caused the loss of the Nicodemus children but it was most likely due to some epidemic like typhoid fever.

The unfortunate location of the Nicodemus farm sandwiched between the surging battlelines and artillery fire undoubtedly would have caused some damage to the buildings. However, the Quartermaster claim filed by Jacob Nicodemus in 1866 makes no mention of damage to buildings. They did claim “12,000 pound of hay that was “taken form the barn” by Union forces occupying the farm following the retreat of the Confederate army.” The claim that was finally paid in 1882, was for “$410.00 worth of corn, straw, and hay”. Even though they did not file a claim for damages to the building, there must have been enough for the Nicodemus’ to build a new home, closer to the barn, the one that exists today.

Hannah and Jacob remained on the farm and had two more children, Alice (1866) and Millard (1869). Jacob passed away at the age of 55, in 1875. Hannah and the two younger children stayed on the farm with the help of Alexander Davis. In 1876, Samuel had married but moved to Kansas where he died ten years later. William Remsburg purchased the farm from Hannah Nicodemus in 1887. It may have been for his son, Cyrus Hicks Remsburg and his new wife, Alice Ann Nicodemus, the daughter of Hannah and Jacob. About this same time, Hannah purchased 44 acres east of the farm from David R. Miller, the pasture just south of the famous Cornfield. A new farmstead would be built for the family and was the home of Hannah, her son, Millard, his wife, Minnie Agnes DeLauney they two daughters and of course Alexander Davis. Unfortunately Millard died in 1910, a year after his mother passed away. Hannah and Jacob Nicodemus were buried at the Fairview Cemetery in Keedysville. This farm was sold and Minnie, the girls and “Uncle Alec” moved to Sharpsburg where Minnie ran the Nicodemus Hotel on Main Street.

In 1886, Alexander Davis purchased a 32-acre tract (blue outlined tract on map above) from Samuel Michael that was adjacent to the farm bordering the West Woods. There was no home on the this property and it may have been lease by Jacob Nicodemus in the previous years. Whatever the reason Alexander may have bought it for is unknown. He only held on to it for ten years before selling it to Cyrus Remsburg in 1896 and it is considered part of the Nicodemus-Remsburg farm today. Alexander Davis lived and worked for the Nicodemus family most of his life, staying with Minnie at the hotel until he died in 1929.

In 1892, the farm was conveyed to Cyrus and Alice. Their daughter, Flossie Elizabeth would marry Otho Flook in 1919 and they purchased the farm in 1941. The Nicodemus farm remains in the Flook family to this day. Even though only a few of the buildings are original, the Nicodemus farm witnessed the some of the first and final shots of the battle, north of Sharpsburg. Like the Samuel Poffenberger Farm, the Nicodemus-Remsberg-Flook farm has been in the family for over 160 years and remains a great example of private stewardship of the land and an eyewitness to history.

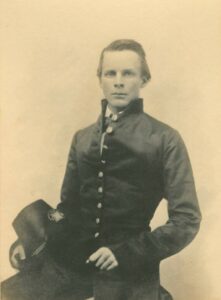

Note: There is some discrepancy between two biographers of the battle of who Alexander Davis really was. According to Clifton Johnson, the farm hand who worked for Jacob Nicodemus was called Alex Root and was described almost like a freed slave. Fred Cross, who visited the Sharpsburg area a number of times, refers to Alexander Davis as the retainer of the Nicodemus family. During his visits, Cross stayed at the Nicodemus Hotel in Sharpsburg, interviewed Mr. Davis and even took his photograph. Also all the census data refers to a Alexander Davis in the Nicodemus household.

Also during the research of the property we attempted to contact the Flook family for an interview and to obtain permission to get on property to take photos. We hope to make this happen in the near future and to update this post as needed.

Sources:

- Ancestry.com, Jacob Nicodemus Family, Census Data 1840-1930. Retrieved from: https://www.ancestry.com\

- Albright, Isaiah H., et al. Landmark History of the United Brethren Church …: Treating of the Early History of the Church in Cumberland, Lancaster, York and Lebanon Counties, Pennsylvania, and Giving the History of the Denomination in the Original Territory. United States, Press of Behney & Bright, 1911.

- Cross, Fred Wilder. Antietam, September 17, 1862, unpublished manuscript, 1921.

- Downey, Brian. Antietam on the Web, 2022 Retrieved from: https://antietam.aotw.org/.

- Ernst, Kathleen. Too Afraid to Cry, Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 1999.

- Huskey, Nancy. Coffman Farm: From Deer Path to Tourism – How a Transportation Network Shaped a Homestead. Masters Degree dissertation, University of Leicester, England. 2004.

- Johnson, Clifton. Battleground Adventures: The Stories of Dwellers on the Scenes of Conflict in Some of the Most Notable Battles of the Civil War. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1915.

- Maryland. Board of Trustees of the Antietam National Cemetery, and 1869-1873 (Oden Bowie) Maryland. Governor. A Descriptive List of the Burial Places of the Remains of Confederate Soldiers: Who Fell In the Battles of Antietam, South Mountain, Monocacy, And Other Points In Washington And Frederick Counties, In the State of Maryland. Hagerstown, Md.: “Free press” print, 1868.

- Maryland State Archives. Maryland Land Records On-Line, Washington County, January 25, 2021. https://mdlandrec.net/main/dsp_search.cfm?cid=WA

- Monroe, J. Albert. Battery D, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, at the Battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862

Providence: Published by the Society 1886. https://archive.org/details/05587901.3518.emory.edu/page/n16/mode/1up - New York Public Library, Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division. “Map of the battlefield of Antietam” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1864. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/185f8270-0834-0136-3daa-6d29ad33124f

- Nelson, John N. “As Grain Fall Before the Reaper”, The Federal Hospital Sites and Identified Federal Casualties at Antietam. Hagerstown, MD. 2004.

- Newspapers.com. Alexander Davis obituary, Morning Herald, June 23, 1924. Retrieved from: https://www.newspapers.com/

- Peters, Richard., Sanger, George Partridge., Minot, George. United States Statutes at Large: Containing the Laws and Concurrent Resolutions … and Reorganization Plan, Amendment to the Constitution, and Proclamations. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1883. Claim Payment for Hannah Nicodemus, 1883. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/books/edition/United_States_Statutes_at_Large/QFh6ABpyZO8C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hannah+Nicodemus,+executrix+of+Jacob+Nicodemus&pg=PA668&printsec=frontcover

- Taggert, Thomas, Map of Washington County. L. McKee and C.G. Roberton, Hagerstown, Maryland 1859.

- Reardon, Carol and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Antietam: experiencing the battlefield through history, places and people, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

- Tracey, Dr. Arthur G. “Land Patents of Washington County, MD. Showing their location on the land-their adjoining tracts- the relationship one to another-plus other related information”. MDLANDREC. Maryland Historic Trust. Retrieved from http://mdhistory.msa.maryland.gov/tracey_fr_wa_cr/html/index.html.

- Williams, Thomas J. C., A History of Washington County, Maryland From the Earliest Settlements to the Present Time, Including a History of Hagerstown, Vol. 2, Part 1. Higginson Book Company, MA. 1906. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_History_of_Washington_County_Maryland/c9AwAQAAMAAJ?hl=en.

- U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

- United States Congressional Serial Set.

- U.S. National Park Service, Antietam National Battlefield, National Register of Historic Place, ANTI-WA-II-477, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1990.

- Williams, Thomas J. C. A history of Washington County, Maryland : from the earliest settlements to the present time, including a history of Hagerstown https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011262603

* Layout design of farmsteads are based on a combination of maps, aerial photographs, and off site visit

Leave A Comment