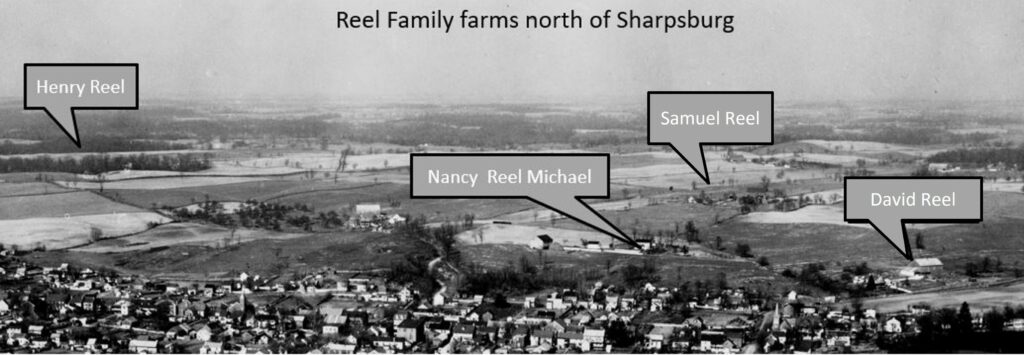

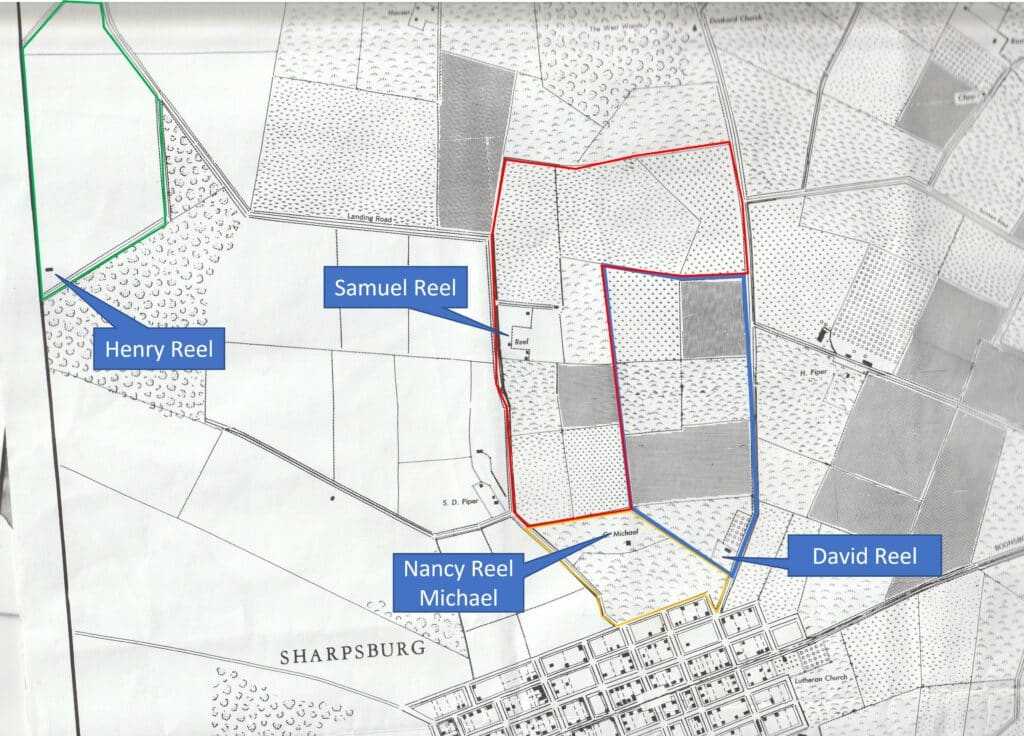

The impact of two large armies during the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862 brought death, disease, and destruction to the civilian population of the small hamlet of Sharpsburg, Maryland not only on that dreadful day but for weeks and months afterward. One of the hardest hit families in the area may have been the Reels. Four siblings all lived on farms just north of Sharpsburg that had been handed down from they father Jacob Reel.

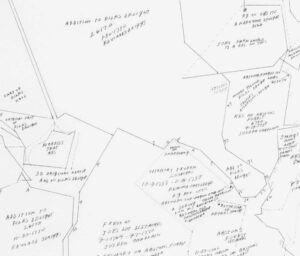

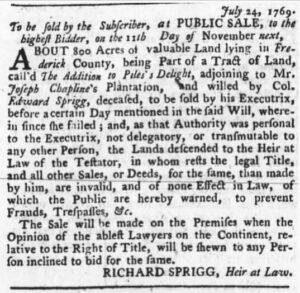

In 1734, Richard Sprigg was granted 500 acres called ‘Piles Grove‘ which was located between Antietam Creek and the Potomac River, just north of the area that would become Sharpsburg.

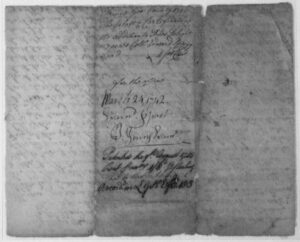

This tract was also known as Piles Delight. In 1743, Colonel Edward Sprigg was granted 117 acres of Piles Delight (Addition). Col. Spring acquired more land and in 1750 had the two patents resurveyed into a tract of 2,617 acres called the Resurvey of the Addition to Piles’ Delight.

In 1751 Col. Sprigg died and according to his will, Res. of Add’ of Piles Delight was divided among his children. With the southern migration into the Antietam Valley by Pennsylvania German farmers accelerating, the Sprigg heirs began to sell off the parcels of their large holdings. By the 1780’s much of the Res. of Add’ of Piles Delight had been subdivided and sold. According to the 1783 Washington County Tax Assessment, there were thirteen owners of “part of R. of Addition to Piles Delight“. One of the new land owners was Basil Beall, who owned 200 acres.

Just twenty years later, Basil Beall would sell a parcel of land which included “part of a tract of land called The Resurvey of the Addition of Piles Delight”, part of a tract of land called Mount Pleasant, and part of a tract of land called Hickory Tavern” to the 36 year old, Jacob Reel. This property was to the north of the new town of Sharpsburg.

We could not trace where the Reel family originally came from, but there were several Reel males that lived here that may have been related. Sometime before 1790, a Joseph Reel moved to the Sharpsburg area, this may have been Jacob’s brother. Joseph would build a mill in 1795, and a stone house (1802) just southeast of town using the water coming from the Big Spring to power the mill. Joseph died in 1831 and the mill was sold.

In 1802, Jacob and his wife Elizabeth had a five year old daughter named Nancy. They would have three more children, all sons; Samuel (1808), David (1810), and Henry (1813). During this time we can assume that Jacob built the farm at the edge of Sharpsburg. In 1813, Jacob added a parcel next to his that was owned by John McPherson and John Brien, both well-known land speculators and owners of the nearby Antietam Iron Works. This doubled the size of his farm. In December 1821, Jacob purchased 179 acres from Leonard Middlekauff. This property was about a mile west of his farm, next to Col. Miller’s. Since it was quite a distance away from his home, Jacob may have been thinking of a future farm for his children.

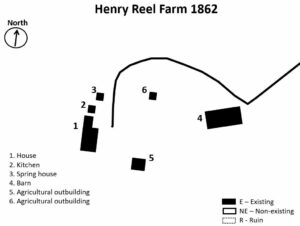

Jacob Reel died in October, 1844 and within a year, his wife Elizabeth died in August 1845. With their passing, the estate was divided among the children. Henry received 117 acres of the farm to the west. It is very likely that Henry built most of the structures on this farm and was already living there at the time of his parents’ death. Henry married Mary Stine in 1836 and they soon had a daughter. Mary died in 1840, possibly during childbirth as their next child, a son Jacob H. Reel, also died in 1840. Henry remarried Maria Houser in 1842, but Maria died in 1847. Henry married a third time to Barbara Ann Stonebaker in 1849 and together they would have nine children.

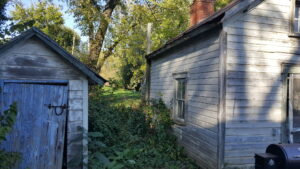

When the farm that Henry lived on was sold in 1873 it was said, “This farm is well improved and under good fencing. It has upon it a good substantial Dwelling House. A Large Barn, Corn Crib, Wagon Shed, and many other buildings. There is also a fine orchard, and a variety of fruit trees upon this farm, as well as good Timber and never failing water.“

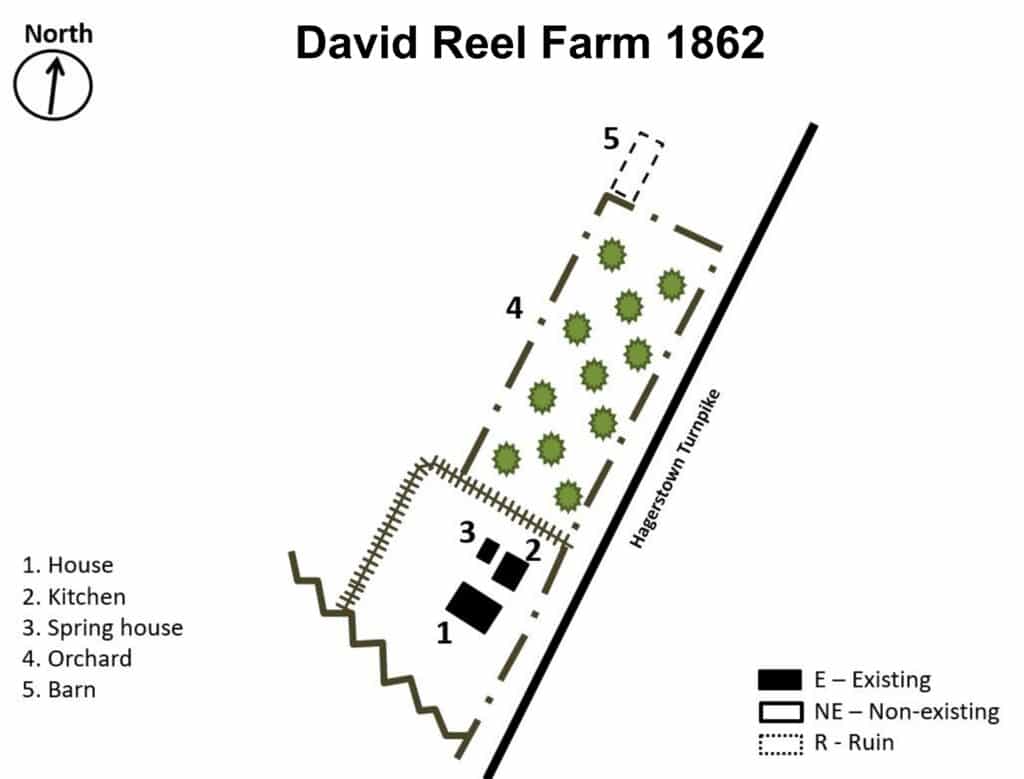

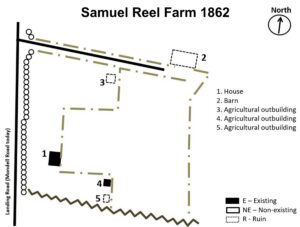

Samuel Reel took over the 90 plus-acre parcel north of the family homestead, leaving the oldest brother, David Reel at the farm just outside of town. David married Ann Maria Banford a few months before his father died in 1844. Together they would have eight children, but two would die before they reached the age of two. Ann Maria died in early 1859 and there is no indication that David ever remarried. Samuel’s farm seemed to be a bit more elaborate, When the property was sold in 1879, the advertisement listed a stone house with a basement with four rooms and a kitchen below and the summer kitchen annexed into the house. The farm also include a smoke house, root cellar, a blacksmith shop, a stable, a small tenant house, a hog pen and a new corn crib.

Samuel Reel married his first wife Maria Loshbaugh in 1840. Maria and Samuel had no children before Maria died in 1857. Soon after her death, Samuel married Cerusha Ann Price, who was thirty years younger. Their first child was born a year later but they did not have any more children until the later 1860’s and into the 1870’s. It is reasonable to assume that David’s farm was well established much like Samuel’s property but no record of an estate sale can be found.

As for Nancy Reel, she married Adam Michael in 1817. The following year Adam purchased a house in Sharpsburg at the corner of what is today East Main Street and North Church Street. It is said that Adam was a wagonmaker and had a shop by the house. Nancy and Michael had six children, three boys and three girls. Their one daughter, Ann Sophia died at the age of 16 in 1840.

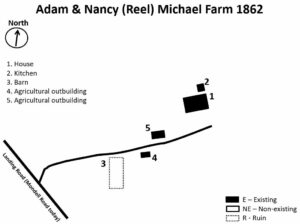

Adam was also a farmer and owned some tracts of land on what was known as Green Hill. This land was east of the Reel homestead and was part of the original tract of land that Jacob Reel purchased in 1802 from Basil Beall. It is possible that this property was given to Nancy or that Adam Michael purchased the property from the Reels. Either way, Adam began building the house in 1854 and expanded the farm to include a kitchen, bank barn and a number of agricultural buildings.

The Reel family were members of the Lutheran Church and owned enslaved persons prior to the Civil War. According to the 1850 Slave Schedule, Henry owned a 50 year old male and on the 1860 schedule, Samuel owned a 61 year old male. This may have been the same individual but there is no record of his name. According to county history, “the Michael family were strong Democrats, and on several occasions the father [Adam] and sons were stoned from the polls by some of the Republican elements of the town and not allowed to vote”. When the war begins, the Michael’s are avid Southern supporters.

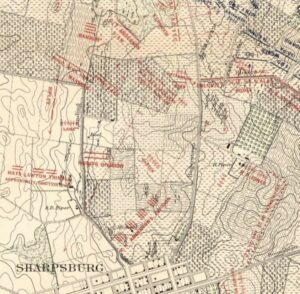

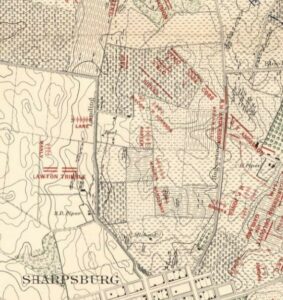

On September 15, 1862 the Reel and the Michael families found themselves in harms way of an approaching battle. General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia converged on the small hamlet of Sharpsburg and the surrounding farmsteads. The main battle line of the Lee’s forces would be to the east of the Hagerstown Pike and north of the Dunker Church. Initially the Reel families may have stayed at home, but when the battle erupted at daybreak on the morning of the 17th they probably evacuated to safety at the farm of Henry to the west.

By 7:30am, Rebels from Stonewall Jackson’s Division under the command of General John R. Jones had fallen back across Samuel Reel’s farm to regroup. Samuel’s barn was quickly established as a first aid station and evacuation site to move Confederate wounded further back from the battle to the hospitals. Sharpsburg resident and historian, John P. Smith who was seventeen at the time of the battle recalled the horrific scene of the Reel hospital, “While staying at Mr. Reels I saw a number of wounded and dead Confederates brought into the yard; some were having their limbs amputated, others horribly mangled were dying. One man in particular I shall never forget. His entire abdomen had been torn and mangled with a piece of exploded shell. He uttered piercing and heart rendering cries and besought those who stood by for God’s sake to kill him and thus end his sufferings. Death came to his relief in a short time and he was hastily buried in a shallow grave dug in the orchard nearby.”

Within the hour, John Bell Hood’s Confederate Division was forced to withdraw to the farm after their devastating counter-attack into the Cornfield and East Woods. At the same time, Confederate reinforcements were marching across the Michael and Reel farms towards the West Woods and the Sunken Road, while Colonel Stephen D. Lee’s artillery battalion redeployed on the high ground of Samuel Reel’s cornfield overlooking the Hagerstown Pike hoping to repeal the Union Second Corps advance.

Captain Henry W. Addison of the 7th South Carolina Regiment recalled their casualties after their attack across the Hagerstown Pike. Writing to Ezra Carman in 1898, Addison said that they were “charging right over the crest of the hill (a green cornfield on our right) where we found the Federals, who had fallen back under it, with innumerable Cannon and numbers of lines of Infantry ready and awaiting us. So rapid was the Federal fire of grape, Canister and Cannon balls of large size together with their Infantry fire, that we lost in Killed and wounded about three fourths of our number in fifteen minutes.

I was shot down by a grape shot. In hobbling back to the rear, I crossed back over a brick or stone wall of the Public Road, near where we turned into line of Battle to the Right, to a Barn, I think of brick, where were numbers of our wounded [were] Col D Wyatt Aiken lying among them,” Colonel David Wyatt Aiken, commander of the 7th SC, had received a gunshot wound to the chest and not expected to survive. Aiken’s brother, Augustus was also in the regiment but serving on McLaws’ staff, saw to his brothers’ care and took him across the Potomac that evening to Shepherdstown.

By about noon, the Rebel lines were breaking at the Sunken Road and around the Dunker Church. Lee and Longstreet were quickly setting up a hasty defensive line along the Hagerstown Pike and west of the Green Hill ridge with the shattered Confederate brigades. Along the ridge five artillery batteries – 23 guns, were placed the stop the Union breakthrough. With Rebel casualties mounting on the Samuel Reel farm and Union counter-battery fire landing all around, some of the wounded were evacuated to the Henry Reel farm just to the west. While this was happening, Capt. Adison added that “The fire of the Federal Batteries on this point was terrific after making several futile efforts, in the short intervals of their guns to cool, I final got off some hundred of yards toward the Town, I looked back, and saw that the Barn or building had been fired, and suppose some of our wounded were burned to death.” This was also witnessed by Sergeant George W. Beale of the 9th Virginia Cavalry. Beale wrote, “A percussion shell from one of the (Federal) batteries, on the sloping hill beyond the Antietam, striking a ledge of rock close by, was exploded, much to our peril and that of the barn, which presently took fire over the wounded men, and to the grim horror of the battle, added those of its flame and smoke”. The large barn was filled with hay and ignited instantly, burning it to the stone foundation. Inside, an unknown number of wounded Confederates had perished.

Lee’s and Longstreet’s seemingly impregnable defensive line west of the Hagerstown Pike along the Reel Ridge and the Piper Farm was enough to prevent the exhausted Union troops from continuing their advance. As dusk began to settle in, the battle ended. That evening, Lee met with his generals for a Council of War to discuss the situation of the army and whether they should withdraw that evening. Story has it that Longstreet was late arriving and Lee was concerned that he may have been wounded or worse. When he arrived at the meeting, relieving Lee’s anxiety, Lee is reported to have said, “There’s my Old War Horse“. Longstreet is said to have been late because he stopped to help put out a fire. We do not know where that may have been, but before the guns fell silent Samuel Reel’s barn had been struck by Union artillery and burned down.

That evening, into the next day before the Confederates withdrew across the Potomac they began the dreadful task of burying their dead. Across the Reel farms, well over fifty Rebel soldiers were interred. Some of these men include Privates James A. McDougal and Levi T. Butler of the 12th Mississippi of R.H. Anderson’s Division near the Hagerstown Pike. In David Reel’s orchard, two soldiers were buried, one unknown. The other is listed as John B. Smith but it may have been Jerome B. Smith. Smith was a 28-year old farmer, serving as a private in Company F, 2nd Mississippi Infantry. That summer, Smith’s acts of bravery during the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31 earned him a place on on the Confederate Roll of Honor.

The same was true at the Nancy and Adam Michael farm. Samuel Michael wrote a letter to the brother David in Indianapolis describing the battle and the dead on their farm; “The fight was a dreadful one. The Rebels held this side of Antietam. The line of battle extended from Middlekauffs down to Joseph Sherrick’s bridge. At this side of Antietam Jackson held Samuel Mumma’s farm and that end. Longstreet in the center and General Tombs Sherrick’s bridge. The graves are as common as cornstalks are on a 40-acre field. We have about 26 buried in one of our fields.” Samuel was not that far off, according to the Bowie list there were “Twenty-eight Unknown * In Adam Michael’s field east and south of his pond field.”

Back at Henry Reel’s farm at least eight soldiers had been buried near his orchard. One of the marked graves was Lieutenant James G. Flemming. In February 1862, young James enlisted as the First Sergeant in Company A of the 49th North Carolina Regiment. He was commissioned 2nd Lieutenant of the Company on 15 July 1862. James’ older brother John, was the Major in the regiment. As the fighting was ending near sunset, James was killed by Federal artillery fire from across the Antietam. James was just two days shy of his 19th birthday.

After Lee’s army retreated back into Virginia, the Federal army resumed the horrific undertaking of not only burying the dead, but taking care of the Confederate wounded that remained behind. A hospital was established at the town home and on the farm of Adam Michael. In Samuel’s letter to his brother David, he describes the scene, “The hospital was in our parlor for several weeks. I do not know how many died in it. They have left now. It looks like a hog pen. Your house that you lived in was also a hospital by the Yankees. They had as high as 90 in there. They burned all of the fence around it. It is smart riddled from the Yankee shells. Such thundering and roaring you never heard since you were born. You would have thought the day of judgement had finally come if you would have been there.” Later in the letter Samuel paints the picture of the destruction of not only their farmstead, but the farms all around Sharpsburg. He says. “The Yankees took all of our corn about seven hundred bushels, about three hundred bus. of potatoes, 27 loads of hay destroyed, several hundred bushel of wheat in the ricks, it was hauled away. They stole all the horses. Killed nearly all of our hogs and sheep. Stole all our beef and took all of the apples — hardly left the trees stand. Our loss is upwards of two thousand dollars. They have refused to pay us anything yet.” In closing his letter, Samuel wrote a post-script about his uncle’s farms, “P.S. David Reel and Samuel Reel lost their barns — both burned down by the Yankees.”

The death and disease ran rampant across the Sharpsburg area but especially among the Reel/Michael family. A month after the battle, Elizabeth Michael died from typhoid fever on Oct. 24th. The following month, her mother Nancy died with the disease as well. Samuel was the one who had to tell his brother David of the dreadful news. He wrote, “I am sorry that I did not answer your note earlier. It was on account of the family being ill. Elizabeth took sick and died from typhoid fever the Doctor says. She had been sick and was doing well on Sunday, previous to her death. She walked out into the garden and looked at her flowers. I was certain that she was going to recover.” Samuel continued about his mother, “Worst of all the disease of the hospital has affected three of our family. Mother died with the disease on the 25th day of November. She was buried today. Mother complained but a short time was taken with three severe hemorrhage — took place about 12 o’clock at night. She died the next day 10 minutes before two. … I never experienced such a night as that was. I had to do what I never expected I would have to do. I must close.”

The next month, the 2-year old son of Henry and Barbara Reel, John died on December 15, 1862. The complications from the fever may have lead to the the death of young Samuel, the son of Cerusha and Samuel Reel; and Catherine Michael, the adult daughter of Adam Michael. Both had died in August 1864.

Caleb Michael, the youngest of the three brothers acquired the farm after his father died in 1873. Adam was buried next to Nancy in the Mountain View Cemetery in Sharpsburg. Caleb continued to live and farm the property until 1907 when he passed away. With Caleb’s passing the farm was sold outside the family. Today, Green Hill Farm is owned and operated by Erin Mosher as a wedding and event venue.

Soon after Henry Reel died in 1873, his farm was sold. At the time of his death, Henry had eight children. Sometime after Henry’s death, Barbara moved to Panola, Illinois with the four younger children. She died in 1880 of consumption and was buried in Illinois. Henry is buried in the Mount Calvary Lutheran Cemetery in Sharpsburg with his parents and other brothers. Today the farmstead of Henry Reel is privately owned by Antietam Meadow Farms, LLC.

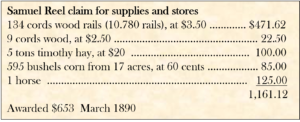

Samuel had filed a claim for supplies, and stores taken or used by the Federal forces after Antietam for a total of $1,161.12. The claim had not been settled until after Samuel died. According to the Court of Claims findings in February, 1890 they granted $653 to the administrator of Samuel Reel’s claim, George A. Davis.

Samuel died in January of 1879 with four children all under ten years old. The farm must have been sold that year because in 1880, Cerusha was living in Sharpsburg with the children. Since 1989, the Samuel Reel farm has been under the stewardship of the American Battlefield Trust and the barn has been restored.

No record of any claim being filed by David Reel has been located and David died in 1880. The farm was taken over by his son Thomas, but it was sold a few year later. The David Reel farm is now under the stewardship of the American Battlefield Trust who purchased the bulk of the farm in 2000, except for the dozen-plus homes along the Sharpsburg Pike.

Thomas and his family become the tenants of the Piper farm from 1908 until 1932. One of the few photos found of the Reels, is of Thomas’s family standing in front of the Piper house in 1916. The photo shows Thomas Reel on the far right with his ten children.

Two of the younger men standing in the back were Lester J. Reel and Howell C. Reel. They would both serve in the United States Army during World War I. Lester did not deploy to overseas while Howell was with an engineer unit in France. Howell died of pneumonia on November 25, 1918. Their cousin, Victor A. Reel (grandson of Samuel) also served in the U.S. Army but did not deploy either.

Very little has been written about the Reel/Michael families and farmsteads. Much more research needs to be done, but this provides a glimpse into their lives and an understanding of the devastation and hardships they faced during this period when they were eyewitnesses to history.

Sources:

- Ancestry.com, Jacob Reel Family, Census Data 1840-1930. Retrieved from: https://www.ancestry.com\.

- Clark, Walter, editor, Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War, 1861-1865, 5 vols., Raleigh and Goldsboro (NC): E. M. Uzzell, Nash Brothers, printers, 1901, https://archive.org/details/historiesofsever03clar/page/n189/mode/2up

- Davenport, Grace Historic Structure Investigation: The Piper House, Antietam National Battlefield, Sharpsburg, Maryland. Masters Thesis, Univ. of Maryland. 2020. Retrieved from: https://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/handle/1903/27607/Davenport_Piper%20Thesis.pdf?sequence=1

- Downey, Brian. Antietam on the Web, 2021 Retrieved from: https://antietam.aotw.org/.

- Dickert, D. Augustus, History of Kershaw’s Brigade, Newberry (SC): Elbert H. Aull Company, 1899.

- Ernst, Kathleen. Too Afraid to Cry, Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 1999.

- Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Alexander Gardner, Sept. 1862, Antietam, Maryland. Real’s barn, burned by the bursting of a Federal shell at the battle of Antietam. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from: https://www.loc.gov/item/2018671856/

- Maryland. Board of Trustees of the Antietam National Cemetery, and 1869-1873 (Oden Bowie) Maryland. Governor. A Descriptive List of the Burial Places of the Remains of Confederate Soldiers: Who Fell In the Battles of Antietam, South Mountain, Monocacy, And Other Points In Washington And Frederick Counties, In the State of Maryland. Hagerstown, Md.: “Free press” print, 1868.

- Maryland State Archives. Maryland Land Records On-Line, Washington County, October 25, 2021. https://mdlandrec.net/main/dsp_search.cfm?cid=WA

- Maryland Historical Trust, Sided-Log House, WA-II-412, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, 1976.

- Maryland Historical Trust, Pat Holland Property (D. Reel House), WA-II-1141, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, 1994.

- New York Public Library, Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division. “Map of the battlefield of Antietam” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1864. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/185f8270-0834-0136-3daa-6d29ad33124f

- Nelson, John N. “As Grain Fall Before the Reaper”, The Federal Hospital Sites and Identified Federal Casualties at Antietam. Hagerstown, MD. 2004.

- Sharpsburg Historical Society, Lot Deeds, Lot 55, Adam Michael House. Retrieved from: http://www.sharpsburghistoricalsociety.org/SHS/history%20archives/historyarchives.htm#

- Smith, John Philemon. Reminiscences of Sharpsburg, Washington County, Maryland. From the date of its formation – July 9, 1763

To the present time – Jan. 1st. 1912. Western Maryland Regional Library (WMRL) Retrieved from: https://digital.whilbr.org/digital/collection/p16715coll39 - Taggert, Thomas, Map of Washington County. L. McKee and C.G. Roberton, Hagerstown, Maryland 1859.

- The Maryland Gazette (Annapolis, Maryland) Edward Spriggs Probate, 24 Aug 1769. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/

- The Touch Light and Public Advertiser (Hagerstown, Maryland) Estate of Henry Reel, 19 Nov. 1873; Estate of David Reel, 17 Sept. 1879. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/

- Tracey, Dr. Arthur G. “Land Patents of Washington County, MD. Showing their location on the land-their adjoining tracts- the relationship one to another-plus other related information“. MDLANDREC. Maryland Historic Trust. Retrieved from http://mdhistory.msa.maryland.gov/tracey_fr_wa_cr/html/index.html.

- VintageAerial.com, Henry Reel property. Retrieved from: lhttps://vintageaerial.com/photos/maryland/washington/1989/CWA/21/25

- Williams, Thomas J. C., A History of Washington County, Maryland From the Earliest Settlements to the Present Time, Including a History of Hagerstown, Vol. 2, Part 1. Higginson Book Company, MA. 1906. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_History_of_Washington_County_Maryland/c9AwAQAAMAAJ?hl=en.

- Western Maryland’s Historical Library. Washington County, Maryland, Taxes 1803 Lower Anteatum Hundred, Washington County, Maryland, 1803. Retrieved from: https://digital.whilbr.org/digital/collection/p16715coll46/id/82/rec/11.

- Western Maryland’s Historical Library. Washington County, Maryland, Sharpsburg service men WWI by Chris Vincent. Retrieved from: https://digital.whilbr.org/digital/collection/p16715coll21/id/1114.

- U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

- United States Congressional Serial Set. Court of Claims for Samuel Reel, 1891. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/books/edition/United_States_Congressional_Serial_Set/IUlHAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=Samuel%20Reel%20%20

* Layout design of farmsteads are based on a combination of maps, aerial photographs, and on site visit

I think the labeling of the Reel farms may have an error. The farm labeled ‘Samuel Reel’ was actually that of David Reel. See ”Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day’ by William A. Frassanito; P. 258, 266-267.

Thank you for your interest in our “Farmsteads” blogs. You are correct that in the Frassanito book the Gardner photo is labeled as the “David Reel barn”. However, research has found that is a mistake. Based on property records and damage claims, David Reel’s property adjoined the town on the Hagerstown Pike and Samuel Reel’s farm was to the north of his brother’s. Both barns were destroyed by fire. This is also brought to light in Steve Cowie’s new book, “When Hell Came to Sharpsburg”.

I just discovered this website; I am an ancestry family researcher, and I just moved from Illinois to this area ironically. Ive recently discovered all my Michael/s family ancestors out here. I am an OIF vet and its been a bucket list to go and visit all the civil war battle fields out here. I JUST discovered this reading about the Reel/Michael family. I have tracked my ancestors to that originated from the sharpsburg MD area, and virginia and west virginia to a couple burried in the Sharpsburg MD german lutheran neighborhood cemetery. the first couple that came to america are burried there with the last name Michael. They came over with the lutheran migration from Meizheim germany, They came to sharpsburg helping establish the lutheran church I believe because their children are christend at the oldest frederick maryland lutheran church and Ive read they helped establish that church as well. I found my distant german grandmothers gravestone in the neighbor old german plots, but I can’t find the husband , I’ve seen pictures online that there were grave stones piled up and they were so old, they were crumbling. my last name is Michaels, my great grandfather added the S. IF there is anyone in the area that is knowledgeable on the Michael family and the church, I would greatly appreciate connecting and driving over to visit and talk and gather research. Thank you