Perhaps one of the least known and seldom visited farmsteads at Antietam is the Alfred Poffenberger farm also known as the Mary Locher cabin. One of the oldest historical structures in the area, many visitors traveling to or from Antietam along Route 65 do not realize that this farmstead was at the center of the most ferocious fighting in the West Woods.

In the 1730s and 40s, settlers from Pennsylvania began passing through Maryland on their way to Virginia. To entice these German settlers to stay in Maryland’s backcountry, Lord Baltimore issued a proclamation in 1732, “offering 200 acres of land in fee, subject to a four shilling per year quitrent per each 100 acres to any family who would settle and work the land.” The opportunity for large land tracts attracted speculators like James Smith, Dr. George Stuart, Col. Edwin Sprigg and Richard Sprigg.

As the migration of settlers traveled south from the Cumberland Valley into the valley of the Antietam, they would follow a trail that would lead them to a ford on the Potomac River. Today this ford is known by a number of names: Pack Horse Ford, Boteler’s Ford, Blackford’s Ford or the Shepherdstown Ford. The trail that the early settlers traveled became known as the “Waggon Road” and was referenced in many of the land patents of the day. In 1734, Richard Sprigg was granted 500 acres called ‘Piles Grove‘ which was located between Antietam Creek and the Potomac River, just north of the area that would become Sharpsburg. Also sometimes referred to as ‘Piles Delight‘, the property was described as “beginning at a White Oak near a small branch and near a larger spring.. about a mile from a road called the Waggon Road…” The tract of land on which the Alfred Poffenberger farm is located, was first surveyed and patented by Richard Sprigg.

The Alfred Poffenberger farm or Mary Locher cabin.

Less than ten years later, in 1743, Colonel Edwin (Edward) Sprigg was granted a portion of the Piles Delight tract.

In 1750, Col. Sprigg had two patents resurveyed into a tract called Piles Delight (Addition and Resurvey) which totaled 2,617 acres. It was very typical of eastern Maryland land speculators to lease or sell smaller parcels of land to the arriving settlers. During this time parcels of the property were probably leased to tenants. Although nothing is known of the builder, it is believed that the log structure on the property today was constructed before 1760. When Col. Sprigg died, his will divided the tract to his children, but his son Frederick would later sell the entire tract to David McMechen in 1791.

Following the death of David McMechen in 1811, the final 600 acres of the Resurvey of the Addition of Piles Delight was put up for sale. The parcel was quickly purchased for $19,300 by John McPherson and John Brien, both well-known land speculators and owners of the nearby Antietam Iron Works. By 1814, they had sold 225 acres to Philip Grove for $13, 500. Michael Havenar also purchased a parcel just to the north of Grove, which would eventually become the Nicodemus Farm.

The Jacob Grove homestead was just west of Sharpsburg.

The Grove family in Maryland had descended from the German settlers of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Hans Groff had emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1695. His grandson, Jacob had moved to Maryland in 1765 and their last name was changed to Grove. Jacob’s son Philip would become one of the leading merchants in Sharpsburg, owning large estates in and around town. One of these estates was known as Mount Airy, a large farmstead just west of town which had been originally owned by the Chapline family. Philip had purchased the property in 1821 and completed the building of the house, which became the Grove homestead.

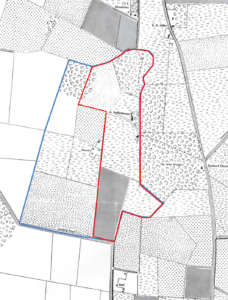

The red line represents the approx. boundary of the Mary Grove Locker parcel and the blue boundary was the Joseph Grove parcel.

Upon Philip’s death in 1841, Mount Airy was acquired by his youngest son, Stephen P. Grove. The other tracts of land in Philip’s estate were divided among his other children. The 225 acre farm on Resurvey of the Addition to Piles Delight was divided between his daughter Mary Grove Locker and his son Joseph Grove. The eastern half of the property, that Mary received, included a dwelling, a large bank barn, a root cellar and several outbuildings. Joseph was most likely already living in the large house on 112 acres on the western portion of the property. The house still stands today. Joseph Grove’s property would eventually become the Jacob Hauser farmstead.

The foundation of the bank barn recently restored by the NPS.

The root cellar by the dwelling.

Westerly view to the Hauser farm.

The log constructed cabin, pre-circa 1760.

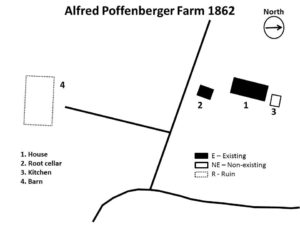

Mary Grove had married Jacob Locher of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The young couple may have lived at the farm she inherited from her father, but most likely it was leased to tenants. By 1860 the original 16 x 16 foot round-log cabin had been expanded with additions to its north and south end. The southern end was probably a large parlor with a sleeping loft and the northern addition including a large working fireplace and wainscoting which suggests it was built as a kitchen. A set of winding box stairs in the kitchen led up to another sleeping chamber.

On March 2, 1858, Alfred Poffenberger married Harriet Hutzel. According to the 1860 census they were residing at the Mary Locher farm along with a one year old son, William. Also listed was a 10 year old named Emma Ziah, and Peter Krutzer, a 28 year old farmhand. Alfred’s uncle, Joseph, had a farm about a mile to the north of the Locker house. His cousin Samuel was soon to be married and they would then move to an established farm just a half a mile to the east of Alfred, off the Smoketown Road. Like his relatives on the surrounding farms, Alfred had harvested his crop of wheat, rye, corn and hay before Confederate soldiers started to occupy his farm on September 16, 1862.

Sept. 17th – 9:00-9:30AM

It is unknown where Alfred Poffenberger and his family went during the battle, but it is certain that they left in a hurry. According to one Confederate soldier who found “the cabin” abandoned just hours before the fighting, he found two loaves of fresh bread which relieved his hunger. By the early morning hours, Confederate forces were rapidly moving across Alfred Poffenberger’s fields. Artillery had set up near the barn and other positions were established by Jacob Hauser’s house and the ridge overlooking the Nicodemus farm. Around mid-morning the fighting was creeping closer to the Poffenberger farmhouse through the West Woods. As Major General John Segdwick’s Union division was about to break out of the woodlot, Confederates under Major General Lafayette McLaws and Brigadier General John Walker struck the federal forces. The farmstead was engulfed in the confusing battle for the West Woods. The ebb and flow of the battle was happening along the lane in front of the cabin. Finally the Confederates pushed the Union soldiers through the West Woods and back across the Hagerstown Pike.

View across MD Route 65 in front of the A. Poffenberger farm to the 15th Mass. monument

The Poffenberger barn had become an ambulance station for the Rebel forces. As the wounded gathered,

ambulances and wagons arrived to transport them to a field hospital that had been established outside of Sharpsburg on the Shepherdstown Road at the David Smith farm. Two days later after the Confederate Army retreat back across Shepherdstown Ford, a burial detail from the 15th Massachusetts dug a 25 foot trench near the cabin by the garden to bury their comrades.

The 5,300-man Union division that advanced through the West Woods was wrecked, suffering over 2,200 casualties in less than thirty minutes. The Confederates would suffer almost 2,000 casualties as well. One Rebel soldier attempted to describe the fighting in the West Woods stating, “We were in the hottest part of the fight under Jackson, and for me to give an idea of the fierceness of the conflict, the roar of musketry, and the thunder of artillery is as utterly impossible as to describe a thousand storms in the region of Hades.”

The amount of damage to the Alfred Poffenberger cabin and buildings must have been very substantial considering the fighting that occurred there, however Alfred’s claims do not reflect that. It is possible, that since it would be very hard to determine whether the damage was caused by Confederate or by Union troops, Alfred did not include structural damage in the two claims he submitted to the Federal government. He would receive $144.30 for stores that included wheat, hay, and corn taken between September 20-27, 1862 and another $661.40 for corn, rye, and hay that was taken September 30, 1862.

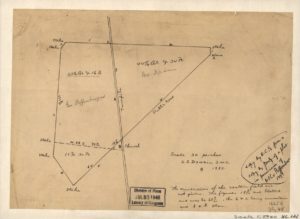

Survey of the property of George Poffenberger and Mrs. Nicodemus by S.S. Downin, in 1883.

After the battle, the Poffenberger’s briefly moved into a tenant house at his Uncle Joseph’s farm. He continued to be a tenant of the Locher farm until after 1870, when he moved his family to Iowa. The next tenant of the log house may have been his younger step-brother George Poffenberger, but only for a short period. By 1883, George had purchased 65 acres from David R. Miller. This parcel included the entire West Woods east of the cabin to the Hagerstown Pike. George immediately built a house there, while renting the Locher farm. In 1898 George Poffenberger would purchase the Locher farm from the heirs of Mary Locher.

The property would remain in the Poffenberger family until 1991 when it was sold to the Conservation Fund and donated to the Antietam National Battlefield. Since that time the National Park Service has conducted archaeological investigations around the house site and constructed a temporary canopy in order to protect the cabin during the stabilization and restoration process. In the future, the National Park Service would like to create an interpretive hiking trail through the Alfred Poffenberger farmstead to continue to tell the story of the West Woods and the civilians involved. The Alfred Poffenberger farm was an eyewitness to the history of this desperate fight in the West Woods.

The Alfred Poffenberger farmstead today.

-

Barron, Lee and Barbara Barron, The History of Sharpsburg, Maryland: Founded by Joseph Chapline, 1763. Sharpsburg: self-published, 1972.

-

Buchanan, Jim, Walking the West Woods, 20 March 2017. Retrieved from http://walkingthewestwoods.blogspot.com/search?q=Mary+Grove+Locher+Cabin%2C+Poffenberger+Farmstead

-

Curci, Jane. Mary Poffenberger: Information about the Poffenberger Family, 20 March 2017. Retrieved from http://www.genealogy.com/forum/surnames/topics/poffenberger/210/

-

Gallagher, Gary W., Editor, The Antietam Campaign. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

-

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Historical American Building Survey MD,22-ANTI.V,2- (sheet 1 of 5) – Mary Locher Cabin, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/md0837.sheet.00001a/

-

Reardon, Carol and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Antietam: experiencing the battlefield through history, places and people, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

-

Schildt, John W., Drums Along the Antietam. ParsonMcClain Printing Company, 2004.

-

Williams, Thomas J.C., A History of Washington County, Maryland. From the earliest settlements to the present time. Vol. 2: Hagerstown, 1906. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books/about/A_History_of_Washington_County_Maryland.html?id=c9AwAQAAMAAJ

-

Early Colonial Settlers of Southern Maryland and Virginia’s Northern Neck Counties Edward Sprigg. Retrieved from http://www.colonial-settlers-md-va.us/getperson.php?personID=I013535&tree=tree1

-

Walker, Kevin M and K. C. Kirkman, Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

Very nice!

THANK YOU. We’re so glad you liked this blog about the farmsteads. Each month we look forward to providing some information about the farms and the families whose lives were forever changed by the Battle of Antietam.

It has been six years since you posted this study of farmsteads of Antietam. I wanted to say how valuable these have been. Excellent research on an aspect of the Antietam story that is often overlooked.

Jim – THANK YOU. We’re so glad you liked this blog about the farmsteads. The other side of the story of Antietam is about the families whose lives were forever changed by the Battle of Antietam.