Some of the earliest land patents of the future Washington County are dated between 1730 and 1740, and they were granted to men who never intended on live on the land. One of these men was Dr. George Stuart of Annapolis who was granted 4,450 acres of land in western Maryland on March 7, 1732. In 1739, Stuart transferred 208 acres to a planter from Prince George’s County named James Smith. It’s believed that Smith lived in the area, as he was surveying lands in the future Frederick and Washington counties and was an attorney for the Frederick courts. This 208 acres was patented “Smiths Hills” and was the future location of what we know today as the Newcomer Farm.

According to the patent, “Smiths Hills” began at “a bounded white oak standing on the side of a hill with a quarter of a mile of the Waggon Road that crosses Anteatom and running thence south“. Over the next fifteen years, Smith continued to add land to his holdings and by 1756 the “Resurvey of Smiths Hills” contained 510 acres. By the 1750’s, colonial interest and the French and Indian War lead to more permanent inroads into the backcountry. Smith petitioned Frederick County for the building of both a ford across the Antietam Creek and a new road, because he intended to build a mill along the creek on his land. Smith also knew that an improved roadway through his property would not only increase the value of his land but that of the surrounding area. Although Smith did not build a mill, “he had set the groundwork for the future development of the milling industry on the property” and a new road would eventually be built from Red Hill to Swearingen’s Ferry on the Potomac at Shepherdstown.

As the French and Indian War was ending, Christian Orndorff, a millwright who was from Lancaster County, arrived in the area in 1762. Now that the region was safe and open for settlement, Orndorff was looking for a suitable site to build a grist mill and he found it along the Antietam Creek. Christian Orndorff purchased 503 acres of Resurvey on Smiths Hills and 11 acres of Porto Santo, another nearby patent, from James Smith. “The deed conveys property with orchards, gardens, feeding woods, and underwoods in addition to the rights and profits associated with its location along Antietam Creek“.

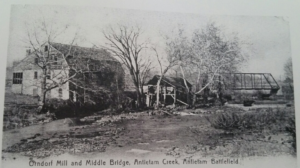

Looking across the Antietam Creek at the Joshua Newcomer farm and mill. The house was the original Orndorff dwelling and no longer exists. (Alexander Gardner; LOC)

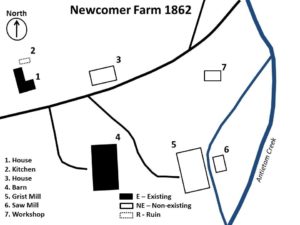

Orndorff built a large house of logs and sheathed it with weatherboard siding. This large three-story home had two chimneys and six fireplaces. Just in front of the house he constructed a large barn, a grist mill, a saw mill and a workshop along the Antietam Creek. The mills were powered by water diverted from the creek through a mill race that Orndorff built. He also farmed crops of wheat and corn. Christian Orndoff named his property “Mount Pleasant”.

“With the new road providing access for farmers to bring their grains to the mill, as well as a route for Orndorff to get the milled grain to market, Orndorff’s business prospered.” Christian expanded his land holding toward Sharpsburg and helped with the construction of other mills along the Antietam. Besides the grist mill and sawmill, Christian established a plaster mill, a cooper shop and other tooling shops which turned his crossing point on the Antietam into a substantial industrial complex.

By the 1770’s resentment of the British government was growing in the colonies, and in the Antietam region Christian was very active in the cause. He helped organize, equip and train men, including the first company west of the Blue Ridge Mountains which was led by Captain Cresap. Christian would become a Major in the Washington County militia and all three of his sons would serve in the army during the American Revolution. His oldest son Christopher was a Captain helping supply the Continental Army with flour and grain. His second son, Christian III was a 2nd Lieutenant in Capt. Reynold’s “Flying Camp” serving in New York. He was taken prisoner on Manhattan Island in November 1776 and was held in New York until exchanged in November 1780. He then joined the 6th Maryland Regiment for the remainder of the war. Henry Orndorff, the third son of Christian II also served as a captain. In 1781, Christian II would return home at the request of General George Washington to operate his flour mill and furnish supplies to the Continental Army.

In the 1780’s Christian II hired a miller to assist with the operations and constructed a house on the east side of the Antietam Creek for the miller and his family. With the war over, Christopher followed in his father’s footsteps and took over the milling operation. Christopher would expand and remodel the mill in 1786. He also built a new dwelling house next to his father’s. It is this house that known today by its 1862 owner – Jacob Newcomer. With Christopher now running the mill, Christian II built a new house just to the northwest of the mill on a piece of his property, which is known today as the Samuel Mumma farm.

In 1796, Jacob Mumma purchased 324 1/4 acres from Christopher Orndorff for £5500. The Mummas arrived in Philadelphia in 1732 and settled in Lancaster County. Like other Germans settling in the area, the Mumma family traveled down the Wagon Road to Sharpsburg. They were accompanied by Joseph Sherrick, Sr. and his family. Sherrick would also purchase property along the Antietam from the Orndorff’s.

Jacob Mumma and his sons lived in the houses and continued to run the mill and farming operations. According to census data the Mummas had a number of farm hands as well as ten slaves. Over the next few years Mumma would acquire “two-thirds of the large land tract amassed by the Orndorff family decades earlier”. Jacob’s son, John began farming on his own at the current site of the Samuel Mumma farm. Tragically, his wife passed away and John moved back to the mill site where he took on the milling operation. “By 1820 the ‘John Mumma’ mill processed 20,000 bushels combined of wheat, rye, and corn as well as sixty tons of plaster”. In 1821, Jacob Mumma and his wife Elizabeth transferred ownership of the mill property to their son John. Around this time, a house and barn was constructed just north of the mill along the creek for John’s son – Jacob, known today as the Parks farm.

The Orndorff or Middle Bridge looking north. The Parks farm can be see in the upper right corner of the photo. (Alexander Gardner; LOC)

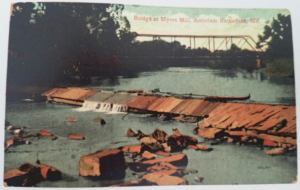

After the turn of the century major improvements in transportation in Washington County began to affect the farming community and the local economy. With the plan to build a National Road from Baltimore to Wheeling, “turnpike fever” spread into Washington County with a number of macadamized toll roads being constructed including “a turnpike leading from Boonsboro through Sharpsburg to the Potomac River” that was completed by 1833. With the chartering of the turnpikes came the need for better bridges across the Antietam Creek. In 1824, Silas Harry built a three-arched stone bridge over the Antietam, replacing the wooden bridge just upstream from the mill. With the construction of the turnpikes and bridges in the county along came the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the ability to transport products from Western Maryland farms to market east.

Business at the Mumma mill was booming but John Mumma suddenly died in 1835 and without a will. His father, Jacob purchased the property back from John’s estate but resold the mill and farm to his younger son, Samuel in 1837. Samuel and his wife Barbara had moved to the farm that John had vacated after his wife died in 1822 (the Mumma Farm). Samuel continued the operations of the mill and farm from there until 1841 when he sold 152 acres to Jacob and John Emmert. The Emmert partnership was short lived and by 1846 the property was purchased by Jacob Miller for $3,000 in a Sheriff’s sale. Miller conveyed the property to Lewis Watson in 1848.

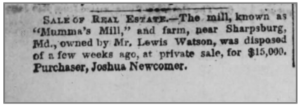

Newspaper clipping of the sale of “Mumma’s Mill” to Joshua Newcomer from The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) · Tue, Jan 10, 1854

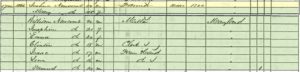

It is believed that Lewis Watson and Joshua Newcomer were partners in the milling operation. The 1850 U.S. Census of Manufactures called the property the “Watson and Newcomer Mill”. Not much is known about the Newcomer family. Joshua married Mary Ann Ankeney in 1837 and together they had seven children. In 1850, Joshua had an young man named David Barkman, a miller, living with them at the farm. That year the mill had processed 31,000 bushels of grain. “Joshua became the owner and proprietor of the complex in 1853 when he purchased it for $19,180” from Lewis Watson. “Between 1850 and 1860 grain production increased in Washington County, especially corn and rye, but also in wheat”.

By 1860, Joshua’s five sons were all working at the mill or on the farm. 22 year-old William, was a miller and his younger brother Clinton, was a clerk. Like his neighbors, Joshua grew corn and wheat, had an orchard, and produced butter, hay, clover, and honey valued at $200. Even though his property was worth over $10,000, with the clouds of war on the horizon, the economic prosperity of both the region and the Newcomer family would fall on hard times.

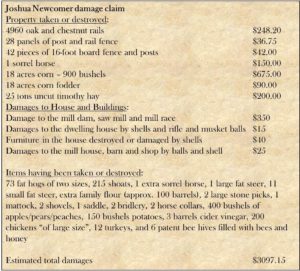

In 1861, a hailstorm destroyed the fields, including Joshua’s wheat crops. “Newcomer had taken out a loan from [Jacob] Miller’s mother and when it was called in he transferred it to someone else”. With the Newcomer property situated along one the main thoroughfares in the area, and at the crossing of the Antietam Creek, soldiers naturally gravitated to the barns, mills, houses, and other buildings at the farmstead for protection and food. This would be the case during the Maryland Campaign as Confederate soldiers were moving along the turnpike toward Sharpsburg on the morning of September 15, 1862. Later that day Union soldiers advanced up to the east side of the bridge and the Antietam Creek.

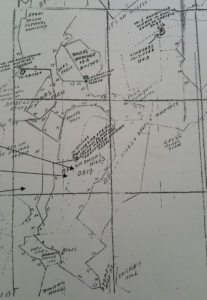

The next morning three companies of Federal troops crossed the bridge and deployed across the Newcomer property, securing the bridge as a future crossing point for the next day’s battle. Throughout the day the Newcomer property was in the center of a cannonade between the Union artillery on the high bluffs on the east side of the Antietam and the Confederate guns along the ridge east of Sharpsburg. It is not known where the Newcomer’s went during the battle, but most certainly they departed, like their neighbors, to the safety of relatives in the area.

The next morning, September 17, as the battle raged to the north of Sharpsburg, Union Horse Artillery was pushed across the Antietam and deployed on the hills of the Newcomer farm. According to Captain John Tidball, of Battery A, 2nd U.S. Artillery, “About 10 a.m., I was ordered to cross the turnpike bridge over the Antietam, where I took a position on the right side of the road. In front, the enemy’s sharpshooters were posted, and there being no infantry at hand to drive them back, I opened fire upon them with canister and gradually worked my guns by hand up a steep ploughed field to the crest of the hill, where I placed them in a commanding position, not only for the enemy directly in front, but for an enfilading fire in front of Sumner’s Corps on the right and that of Burnside on the left of me”.

By mid-day Union infantry had pushed the Confederate skirmishers back up the hill across the Newcomer fields toward Sharpsburg and more artillery occupied the heights to support Gen. Burnside’s advance to the south. By nightfall the Union forces held the high ground along the Antietam Creek and across the Newcomer farm.

Looking west at the Middle Bridge. The Newcomer farm and mill complex are on the far bank to the left of the turnpike while the two houses are on the opposite side of the pike. (Alexander Gardner; LOC)

Looking southwest toward the Middle Bridge and Newcomer barn. The small house with the garden still exists and may be the house built for the miller while the stone house across from it is thought to be the toll house which no longer exists. (Alexander Gardner; LOC)

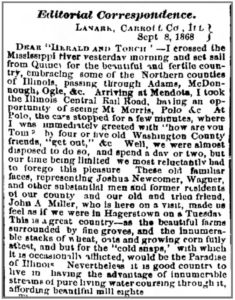

From The Herald and Torch Light (Hagerstown, Maryland) on Wed, Sep 23, 1868 by a man named ‘Tom’ who was travelling through Illinois when he ran into Joshua Newcomer.

By the end of the war the Newcomer family, farm and livelihood was devastated. Now deep in debt, and not wanting to burden his sons with the necessary and significant repairs required, Joshua vacated the farm and the Newcomer family moved to Haldane, Illinois, possibly to live with family or friends from Washington County. By 1880 the Newcomers returned to Washington County, but lived near Clear Spring. In August 1887, Mary Ann passed away, followed by Joshua just four months later in December. They are buried in Saint Paul’s Lutheran Church Cemetery in Clear Spring, Maryland.

After the Newcomers departed, the property fell to a County Circuit Court Trustee and the property was put up for public sale in March, 1866. On August 1, 1867, David Myers purchased the property for $19,050. Within two years he sold it to Jacob Myers and Frederick Miller. Myers and Miller continued farming and operating the mill. By the 1880’s the water-powered flour milling industry was declining and in 1889 the dam was washed away during the “Johnstown Flood”.

The piers of the stone bridge weakened and began to settle in the high water. The bridge was torn down and replace with an iron bridge. By this point Jacob Myers was the sole owner of the property buying Miller’s share of the estate. Jacob Myers continued to reside on the farm until he died in 1901.

Over the next century the property would change hands ten times. During this time the dilapidated old mill was demolished and “the farm’s focus eventually shifted to milk production”. The original Orndorff dwelling was also gone by the mid 1950’s. In 1956 part of the property was transferred to the State Roads Commission as a right-of-way for the improvement of the ‘old turnpike’ into MD Route #34. With the widened road some of the out buildings were removed as the road cut through the property. With the new road came the need to develop acres of the once rich farmland into housing developments. In 1965, Brightwood Acres Inc. purchased the property and planned to “create another suburban community”. Fortunately the Newcomer farm escaped this fate and the property was sold the next year.

By 1999, a new owner had plans for the farmstead. William F. Chaney purchased the property for $290,000.00 with the intent of turning the farmhouse in a museum and giftshop. The following year Chaney began to restore the farmhouse to Secretary of the Interior standards and in October he sold 56.83 acres to the National Park Service. This parcel included the barn and the land south of the turnpike. Chaney, who traced his roots to Gen. Robert E. Lee, also wanted to erect sculptures of Lee, Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart around the house which was now the War Between the States Museum. In 2003 a statute to Lee was erected just west of the house, but within two years Chaney sold the surrounding 42.6 acres to the Park Service, including Lee’s statue. Chaney retained ownership of about 2.2 acres, including the Newcomer House. Finally in 2007 he sold this last piece to the National Park Service.

In 2010 the Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area opened an Exhibit and Visitor Center at the Newcomer House, working in partnership with the Antietam National Battlefield and the Hagerstown-Washington County Convention and Visitors Bureau. The Newcomer House is very unique because it is one of two period farmhouses that visitors can go into on the battlefield, the Pry House Field Hospital Museum being the other. The Newcomer barn has recently been restored and the house is due for future external restoration.

From the early settlements along the Antietam Creek, to the milling industry and agricultural operations the Newcomer Farm has witnessed the the expansion of America. This expansion improved the transportation in the region with the building of the bridges and turnpikes through the property. It has seen the scars of war, from the French and Indian War through the American Revolution to the turbulent times of Civil War. The property escaped the urban development of the day to become one of the preserved landmarks on the battlefield at Antietam. The Newcomer Farmstead is a unique eyewitness to the history of the Antietam Valley for over 250 years.

Sources:

-

Ancestry.com, Joshua Newcomer Family, Census Data 1850-1880. Retrieved from: https://www.ancestry.com\

-

Ernst, Kathleen A., Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign, Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999.

-

Hayes, Helen Ashe, The Antietam and Its Bridges, The annals of an historic stream. G.P. Putnam’s Sons New York 1910. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/stream/antietamitsbridg00haysuoft#page/n121/mode/2up/search/Orndroff

-

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, The Middle Bridge, Sharpsburg, Washington County, MD. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.md1099.photos/?sp=1

-

Lundegard, Marjorie, Mills and Mill Sites of Western Maryland, September 20, 2000 Retrieved from: http://www.spoommidatlantic.org

-

Maryland Historical Trust, Mount Pleasant or Orndorff’s Mill – Mumma’s Mill, WA-II-106, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, 1975.

https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/Washington/WA-II-106.pdf.

-

Newspapers.com, Newcomer Farm clippings retrieved from: https://www.newspapers.com.

-

Reardon, Carol and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Antietam: experiencing the battlefield through history, places and people, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

-

Schildt, John W., Drums Along the Antietam. ParsonMcClain Printing Company, 2004.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Antietam National Battlefield, National Register of Historic Place, WA-II-106, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1990.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Newcomer Barn, Antietam National Battlefield, Historic Structures Report Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2004.

-

U.S. National Park Service, Parks Farmstead Cultural Landscape Inventory, Antietam National Battlefield, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2011.

-

Walker, Kevin M and K. C. Kirkman, Antietam Farmsteads: A Guide to the Battlefield Landscape. Sharpsburg: Western Maryland Interpretive Association, 2010.

-

U.S. War Department, Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, prepared under the direction of the Antietam Battlefield Board, lieut. col. Geo. W. Davis, U.S.A., president, gen. E.A. Carman, U.S.V., gen. H Heth, C.S.A. Surveyed by lieut. col. E.B. Cope, engineer, H.W. Mattern, assistant engineer, of the Gettysburg National Park. Drawn by Charles H. Ourand, 1899. Position of troops by gen. E. A. Carman. Published by authority of the Secretary of War, under the direction of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, 1908.” Washington, Government Printing Office, 1908. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3842am.gcw0248000/?sp=5.

Leave A Comment